Latvian mythology is the collection of myths that have emerged throughout the history of Latvia, sometimes being elaborated upon by successive generations, and at other times being rejected and replaced by other explanatory narratives. These myths stem from folk traditions of the Latvian people and pre-Christian Baltic mythology.

Religious practices in ancient Greece encompassed a collection of beliefs, rituals, and mythology, in the form of both popular public religion and cult practices. The application of the modern concept of "religion" to ancient cultures has been questioned as anachronistic. The ancient Greeks did not have a word for 'religion' in the modern sense. Likewise, no Greek writer known to us classifies either the gods or the cult practices into separate 'religions'. Instead, for example, Herodotus speaks of the Hellenes as having "common shrines of the gods and sacrifices, and the same kinds of customs."

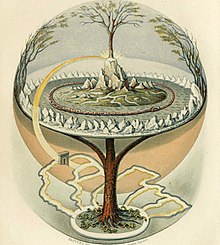

The world tree is a motif present in several religions and mythologies, particularly Indo-European, Siberian, and Native American religions. The world tree is represented as a colossal tree which supports the heavens, thereby connecting the heavens, the terrestrial world, and, through its roots, the underworld. It may also be strongly connected to the motif of the tree of life, but it is the source of wisdom of the ages.

Traditional Sámi spiritual practices and beliefs are based on a type of animism, polytheism, and what anthropologists may consider shamanism. The religious traditions can vary considerably from region to region within Sápmi.

Haitian mythology consists of many folklore stories from different time periods, involving sacred dance and deities, all the way to Vodou. Haitian Vodou is a syncretic mixture of Roman Catholic rituals developed during the French colonial period, based on traditional African beliefs, with roots in Dahomey, Kongo and Yoruba traditions, and folkloric influence from the indigenous Taino peoples of Haiti. The lwa, or spirits with whom Vodou adherents work and practice, are not gods but servants of the Supreme Creator Bondye. A lot of the Iwa identities come from deities formed in the West African traditional regions, especially the Fon and Yoruba. In keeping with the French-Catholic influence of the faith, Vodou practioneers are for the most part monotheists, believing that the lwa are great and powerful forces in the world with whom humans interact and vice versa, resulting in a symbiotic relationship intended to bring both humans and the lwa back to Bondye. "Vodou is a religious practice, a faith that points toward an intimate knowledge of God, and offers its practitioners a means to come into communion with the Divine, through an ever evolving paradigm of dance, song and prayers."

Animal worship is an umbrella term designating religious or ritual practices involving animals. This includes the worship of animal deities or animal sacrifice. An animal 'cult' is formed when a species is taken to represent a religious figure. Animal cults can be classified according to their formal features or by their symbolic content.

Finnic paganism is the indigenous pagan religion in Finland, Karelia, Ingria and Estonia prior to Christianisation. It was a polytheistic religion, worshipping a number of different deities. The principal god was the god of thunder and the sky, Ukko; other important gods included Jumo (Jumala), Ahti, and Tapio. Jumala was a sky god; today, the word "Jumala" refers to all gods in general. Ahti was a god of the sea, waters and fish. Tapio was the god of forests and hunting.

Georgian mythology refers to the mythology of pre-Christian Georgians, an indigenous Caucasian ethnic group native to Georgia and the South Caucasus. The mythology of the Kartvelian peoples is believed by many scholars to have formed part of the religions of the kingdoms of Diauehi, Colchis and Iberia.

Estonian mythology is a complex of myths belonging to the Estonian folk heritage and literary mythology. Information about the pre-Christian and medieval Estonian mythology is scattered in historical chronicles, travellers' accounts and in ecclesiastical registers. Systematic recordings of Estonian folklore started in the 19th century. Pre-Christian Estonian deities may have included a god known as Jumal or Taevataat in Estonian, corresponding to Jumala in Finnish, and Jumo in Mari.

Ancient Celtic religion, commonly known as Celtic paganism, was the religion of the ancient Celtic peoples of Europe. Because there are no extant native records of their beliefs, evidence about their religion is gleaned from archaeology, Greco-Roman accounts, and literature from the early Christian period. Celtic paganism was one of a larger group of polytheistic Indo-European religions of Iron Age Europe.

Snakes are a common occurrence in myths for a multitude of cultures. The Hopi people of North America viewed snakes as symbols of healing, transformation, and fertility. Snakes in Mexican folk culture tell about the fear of the snake to the pregnant women where the snake attacks the umbilical cord. The Great Goddess often had snakes as her familiars—sometimes twining around her sacred staff, as in ancient Crete—and they were worshipped as guardians of her mysteries of birth and regeneration. Although not entirely a snake, the plumed serpent, Quetzalcoatl, in Mesoamerican culture, particularly Mayan and Aztec, held a multitude of roles as a deity. He was viewed as a twin entity which embodied that of god and man and equally man and serpent, yet was closely associated with fertility. In ancient Aztec mythology, Quetzalcoatl was the son of the fertility earth goddess, Cihuacoatl, and cloud serpent and hunting god, Maxicoat. His roles took the form of everything from bringer of morning winds and bright daylight for healthy crops, to a sea god capable of bringing on great floods. As shown in the images there are images of the sky serpent with its tail in its mouth, it is believed to be a reverence to the sun, for which Quetzalcoatl was also closely linked.

Hungarian mythology includes the myths, legends, folk tales, fairy tales and gods of the Hungarians, also known as the Magyarok.

Cantabrian mythology refers to the myths, teachings and legends of the Cantabri, a pre-Roman Celtic people of the north coastal region of Iberia (Spain). Over time, Cantabrian mythology was likely diluted by Celtic mythology and Roman mythology with some original meanings lost. Later, the ascendancy of Christendom absorbed or ended the pagan rites of Cantabrian, Celtic and Roman mythology leading to a syncretism. Some relics of Cantabrian mythology remain.

The Tai folk religion, or Satsana Phi, or Ban Phi is a form of animist religious beliefs intermixed with Buddhist beliefs traditionally and historically practiced by groups of ethnic Tai peoples. It is a syncretic mixture of Buddhist and Hindu practices with local traditional beliefs in mainland southeast Asia. Tai folk religion was a dominant native religion in mainland Southeast Asia until the arrival of Buddhism and Hinduism.

According to classical sources, the ancient Celts were animists. They honoured the forces of nature, saw the world as inhabited by many spirits, and saw the Divine manifesting in aspects of the natural world.

In Slavic mythology, Perun is the highest god of the pantheon and the god of sky, thunder, lightning, storms, rain, law, war, fertility and oak trees. His other attributes were fire, mountains, wind, iris, eagle, firmament, horses and carts, and weapons. The supreme god in the Kievan Rus' during the 9th-10th centuries, Perun was first associated with weapons made of stone and later with those of metal.

The di inferi or dii inferi were a shadowy collective of ancient Roman deities associated with death and the underworld. The epithet inferi is also given to the mysterious Manes, a collective of ancestral spirits. The most likely origin of the word Manes is from manus or manis, meaning "good" or "kindly," which was a euphemistic way to speak of the inferi so as to avert their potential to harm or cause fear.

Trees hold a particular role in Germanic paganism and Germanic mythology, both as individuals and in groups. The central role of trees in Germanic religion is noted in the earliest written reports about the Germanic peoples, with the Roman historian Tacitus stating that Germanic cult practices took place exclusively in groves rather than temples. Scholars consider that reverence for and rites performed at individual trees are derived from the mythological role of the world tree, Yggdrasil; onomastic and some historical evidence also connects individual deities to both groves and individual trees. After Christianisation, trees continue to play a significant role in the folk beliefs of the Germanic peoples.