In music, a tone row or note row, also series or set, is a non-repetitive ordering of a set of pitch-classes, typically of the twelve notes in musical set theory of the chromatic scale, though both larger and smaller sets are sometimes found.

In music, serialism is a method of composition using series of pitches, rhythms, dynamics, timbres or other musical elements. Serialism began primarily with Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique, though some of his contemporaries were also working to establish serialism as a form of post-tonal thinking. Twelve-tone technique orders the twelve notes of the chromatic scale, forming a row or series and providing a unifying basis for a composition's melody, harmony, structural progressions, and variations. Other types of serialism also work with sets, collections of objects, but not necessarily with fixed-order series, and extend the technique to other musical dimensions, such as duration, dynamics, and timbre.

The twelve-tone technique—also known as dodecaphony, twelve-tone serialism, and twelve-note composition—is a method of musical composition first devised by Austrian composer Josef Matthias Hauer, who published his "law of the twelve tones" in 1919. In 1923, Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951) developed his own, better-known version of 12-tone technique, which became associated with the "Second Viennese School" composers, who were the primary users of the technique in the first decades of its existence. The technique is a means of ensuring that all 12 notes of the chromatic scale are sounded as often as one another in a piece of music while preventing the emphasis of any one note through the use of tone rows, orderings of the 12 pitch classes. All 12 notes are thus given more or less equal importance, and the music avoids being in a key. Over time, the technique increased greatly in popularity and eventually became widely influential on 20th-century composers. Many important composers who had originally not subscribed to or actively opposed the technique, such as Aaron Copland and Igor Stravinsky, eventually adopted it in their music.

In music theory, a trichord is a group of three different pitch classes found within a larger group. A trichord is a contiguous three-note set from a musical scale or a twelve-tone row.

In music, the mystic chord or Prometheus chord is a six-note synthetic chord and its associated scale, or pitch collection; which loosely serves as the harmonic and melodic basis for some of the later pieces by Russian composer Alexander Scriabin. Scriabin, however, did not use the chord directly but rather derived material from its transpositions.

In music, a hexachord is a six-note series, as exhibited in a scale or tone row. The term was adopted in this sense during the Middle Ages and adapted in the 20th century in Milton Babbitt's serial theory. The word is taken from the Greek: ἑξάχορδος, compounded from ἕξ and χορδή, and was also the term used in music theory up to the 18th century for the interval of a sixth.

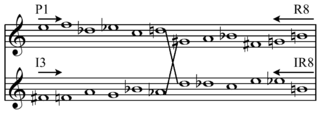

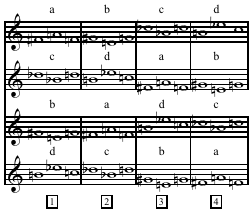

In music using the twelve tone technique, combinatoriality is a quality shared by twelve-tone tone rows whereby each section of a row and a proportionate number of its transformations combine to form aggregates. Much as the pitches of an aggregate created by a tone row do not need to occur simultaneously, the pitches of a combinatorially created aggregate need not occur simultaneously. Arnold Schoenberg, creator of the twelve-tone technique, often combined P-0/I-5 to create "two aggregates, between the first hexachords of each, and the second hexachords of each, respectively."

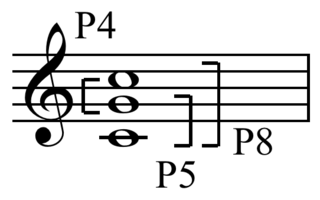

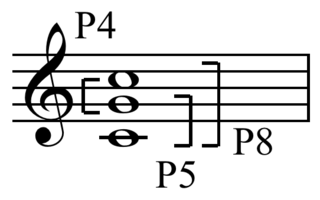

In music theory, complement refers to either traditional interval complementation, or the aggregate complementation of twelve-tone and serialism.

Josef Matthias Hauer was an Austrian composer and music theorist. He is best known for developing, independent of and a year or two before Arnold Schoenberg, a method for composing with all 12 notes of the chromatic scale. Hauer was also an important early theorist of twelve-tone music and composition.

A set in music theory, as in mathematics and general parlance, is a collection of objects. In musical contexts the term is traditionally applied most often to collections of pitches or pitch-classes, but theorists have extended its use to other types of musical entities, so that one may speak of sets of durations or timbres, for example.

In musical set theory, an interval vector is an array of natural numbers which summarize the intervals present in a set of pitch classes. Other names include: ic vector, PIC vector and APIC vector

An all-interval tetrachord is a tetrachord, a collection of four pitch classes, containing all six interval classes. There are only two possible all-interval tetrachords, when expressed in prime form. In set theory notation, these are [0,1,4,6] (4-Z15) and [0,1,3,7] (4-Z29). Their inversions are [0,2,5,6] (4-Z15b) and [0,4,6,7] (4-Z29b). The interval vector for all all-interval tetrachords is [1,1,1,1,1,1].

Composition for Four Instruments (1948) is an early serial music composition written by American composer Milton Babbitt. It is Babbitt's first published ensemble work, following shortly after his Three Compositions for Piano (1947). In both these pieces, Babbitt expands upon the methods of twelve-tone composition developed by Arnold Schoenberg. He is notably innovative for his application of serial techniques to rhythm. Composition for Four Instruments is considered one of the early examples of “totally serialized” music. It is remarkable for a strong sense of integration and concentration on its particular premises—qualities that caused Elliott Carter, upon first hearing it in 1951, to persuade New Music Edition to publish it.

Fritz Heinrich Klein was an Austrian composer.

In music, the "Ode-to-Napoleon" hexachord is the hexachord named after its use in the twelve-tone piece Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte (1942) by Arnold Schoenberg. Containing the pitch-classes 014589 it is given Forte number 6–20 in Allen Forte's taxonomic system. The primary form of the tone row used in the Ode allows the triads of G minor, E♭ minor, and B minor to easily appear.

In music, the all-trichord hexachord is a unique hexachord that contains all twelve trichords, or from which all twelve possible trichords may be derived. The prime form of this set class is {012478} and its Forte number is 6-Z17. Its complement is 6-Z43 and they share the interval vector of <3,2,2,3,3,2>.

In music, an all-interval twelve-tone row, series, or chord, is a twelve-tone tone row arranged so that it contains one instance of each interval within the octave, 1 through 11. A "twelve-note spatial set made up of the eleven intervals [between consecutive pitches]." There are 1,928 distinct all-interval twelve-tone rows. These sets may be ordered in time or in register. "Distinct" in this context means in transpositionally and rotationally normal form, and disregarding inversionally related forms. These 1,928 tone rows have been independently rediscovered several times, their first computation probably was by Andre Riotte in 1961, see.

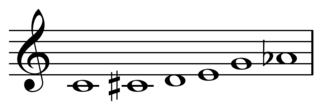

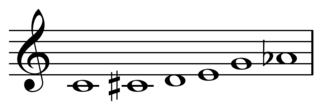

In music theory, the chromatic hexachord is the hexachord consisting of a consecutive six-note segment of the chromatic scale. It is the first hexachord as ordered by Forte number, and its complement is the chromatic hexachord at the tritone. For example, zero through five and six through eleven. On C:

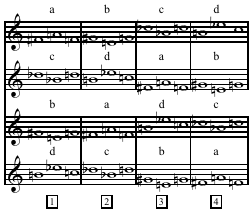

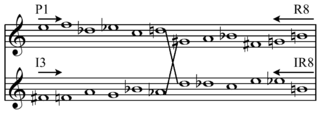

The Tone Clock, and its related compositional theory Tone-Clock Theory, is a post-tonal music composition technique, developed by composers Peter Schat and Jenny McLeod. Music written using tone-clock theory features a high economy of musical intervals within a generally chromatic musical language. This is because tone-clock theory encourages the composer to generate all their harmonic and melodic material from a limited number of intervallic configurations. Tone-clock theory is also concerned with the way that the three-note pitch-class sets can be shown to underlie larger sets, and considers these triads as a fundamental unit in the harmonic world of any piece. Because there are twelve possible triadic prime forms, Schat called them the 'hours', and imagined them arrayed in a clock face, with the smallest hour in the 1 o'clock position, and the largest hour in the 12 o'clock position. A notable feature of Tone-Clock Theory is 'tone-clock steering': transposing and/or inverting hours so that each note of the chromatic aggregate is generated once and once only.

The String Quartet No.1 is a piece for two violins, viola and cello, composed by Robert Gerhard between 1951 and 1955, premiered at Dartington in 1956. This work marks a turning point in Gerhard's style and composition processes, because in one hand, he recovers some old techniques such as the sonata form in the first movement, along with others not as old like the 12-tone technique. Gerhard brilliantly develops, combines and transforms these resources along with new systematic processes created by himself, so that it leads to a new and broad theoretical framework that will be essential to his music thereafter.