Flour is a powder made by grinding raw grains, roots, beans, nuts, or seeds. Flours are used to make many different foods. Cereal flour, particularly wheat flour, is the main ingredient of bread, which is a staple food for many cultures. Corn flour has been important in Mesoamerican cuisine since ancient times and remains a staple in the Americas. Rye flour is a constituent of bread in both Central Europe and Northern Europe.

Semolina is the name given to coarsely milled durum wheat mainly used in making couscous, pasta, and sweet puddings. The term semolina is also used to designate coarse millings of other varieties of wheat, and sometimes other grains as well.

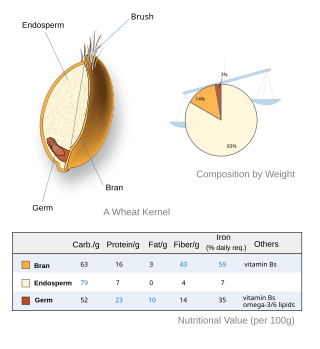

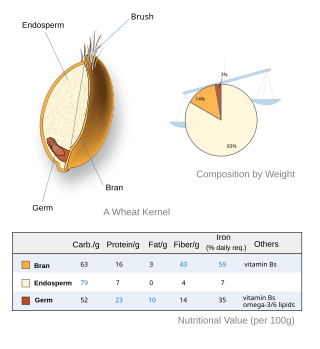

Bran, also known as miller's bran, is the hard layers of cereal grain surrounding the endosperm. It consists of the combined aleurone and pericarp. Corn (maize) bran also includes the pedicel. Along with the germ, it is an integral part of whole grains, and is often produced as a byproduct of milling in the production of refined grains.

White bread typically refers to breads made from wheat flour from which the bran and the germ layers have been removed from the whole wheatberry as part of the flour grinding or milling process, producing a light-colored flour.

Wheat flour is a powder made from the grinding of wheat used for human consumption. Wheat varieties are called "soft" or "weak" if gluten content is low, and are called "hard" or "strong" if they have high gluten content. Hard flour, or bread flour, is high in gluten, with 12% to 14% gluten content, and its dough has elastic toughness that holds its shape well once baked. Soft flour is comparatively low in gluten and thus results in a loaf with a finer, crumbly texture. Soft flour is usually divided into cake flour, which is the lowest in gluten, and pastry flour, which has slightly more gluten than cake flour.

Enriched flour is flour with specific nutrients added to it. These nutrients include iron and B vitamins. Calcium may also be supplemented. The purpose of enriching flour is to replenish the nutrients in the flour to match the nutritional status of the unrefined product. This differentiates enrichment from fortification, which is the process of introducing new nutrients to a food.

Groats are the hulled kernels of various cereal grains, such as oat, wheat, rye, and barley. Groats are whole grains that include the cereal germ and fiber-rich bran portion of the grain, as well as the endosperm.

The germ of a cereal grain is the part that develops into a plant; it is the seed embryo. Along with bran, germ is often a by-product of the milling that produces refined grain products. Cereal grains and their components, such as wheat germ oil, rice bran oil, and maize bran, may be used as a source from which vegetable oil is extracted, or used directly as a food ingredient. The germ is retained as an integral part of whole-grain foods. Non-whole grain methods of milling are intended to isolate the endosperm, which is ground into flour, with removal of both the husk (bran) and the germ. Removal of bran produces a flour with a white rather than a brown color and eliminates fiber. The germ is rich in polyunsaturated fats and so germ removal improves the storage qualities of flour.

A whole grain is a grain of any cereal and pseudocereal that contains the endosperm, germ, and bran, in contrast to refined grains, which retain only the endosperm.

Brown bread is bread made with significant amounts of whole grain flours, usually wheat sometimes with corn and or rye flours. Brown breads often get their characteristic dark color from ingredients such as molasses or coffee. In Canada, Ireland and South Africa, it is whole wheat bread; in New England and the Maritimes, it is bread sweatend with molasses. In some regions of the US, brown bread is called wheat bread to complement white bread.

Maida, maida flour, or maida mavu is a type of wheat flour originated from the Indian subcontinent. It is a super-refined wheat flour used in Indian cuisine to make pastries and other bakery items like breads and biscuits. Some maida may have tapioca starch added.

Refined grains have been significantly modified from their natural composition, in contrast to whole grains. The modification process generally involves the mechanical removal of bran and germ, either through grinding or selective sifting.

Wheat middlings are the product of the wheat milling process that is not flour. A good source of protein, fiber, phosphorus, and other nutrients, they are a useful fodder for livestock and pets. They are also being researched for use as a biofuel.

A wheat berry, or wheatberry, is a whole wheat kernel, composed of the bran, germ, and endosperm, without the husk. Botanically, it is a type of fruit called a caryopsis. Wheat berries have a tan to reddish-brown color and are available as either a hard or soft processed grain They are often added to salads or baked into bread to add a chewy texture. If wheat berries are milled, whole-wheat flour is produced. Wheatberries are similar to barley, with a somewhat nuttier taste.

Sprouted bread is a type of bread made from whole grains that have been allowed to sprout. There are a few different types of sprouted grain bread. Some are made with additional added flour; some are made with added gluten; and some, such as Essene bread and Ezekiel bread are made with very few additional ingredients.

Whole wheat bread or wholemeal bread is a type of bread made using flour that is partly or entirely milled from whole or almost-whole wheat grains, see whole-wheat flour and whole grain. It is one kind of brown bread. Synonyms or near-synonyms for whole-wheat bread outside the United States are whole grain bread or wholemeal bread. Some regions of the US simply called the bread wheat bread, a comparison to white bread. Some varieties of whole-wheat bread are traditionally coated with whole or cracked grains of wheat, though this is mostly decorative compared to the nutritional value of a good quality loaf itself.

A gristmill grinds cereal grain into flour and middlings. The term can refer to either the grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist is grain that has been separated from its chaff in preparation for grinding.

Whole-wheat flour or wholemeal flour is a powdery substance, a basic food ingredient, derived by grinding or mashing the whole grain of wheat, also known as the wheatberry. Whole-wheat flour is used in baking of breads and other baked goods, and also typically mixed with lighter "white" unbleached or bleached flours to restore nutrients, texture, and body to the white flours that can be lost in milling and other processing to the finished baked goods or other food(s).

The Roller Mill was created by Hungarian bakers in the late 1860s and its popularity spread worldwide throughout the 1900s. Roller mills now produce almost all non-whole grain flour. Enriched flour is flour that meets an FDA standard in the United States. Roller milled white enriched flour makes up over 90% of the flour that comes out of the United States.

Flour extraction is the common process of refining Whole Grain Flour first milled from grain or grist by running it through sifting devices, often called flour dressers.