Proposition 215, or the Compassionate Use Act of 1996, is a California law permitting the use of medical cannabis despite marijuana's lack of the normal Food and Drug Administration testing for safety and efficacy. It was enacted, on November 5, 1996, by means of the initiative process, and passed with 5,382,915 (55.6%) votes in favor and 4,301,960 (44.4%) against.

The Marijuana Policy Project (MPP) is the largest organization working solely on marijuana policy reform in the United States in terms of its budget, number of members, and staff.

Mary Jane Rathbun, popularly known as Brownie Mary, was an American medical cannabis rights activist. As a hospital volunteer at San Francisco General Hospital, she became known for baking and distributing cannabis brownies to AIDS patients. Along with activist Dennis Peron, Rathbun lobbied for the legalization of cannabis for medical use, and she helped pass San Francisco Proposition P (1991) and California Proposition 215 (1996) to achieve those goals. She also contributed to the establishment of the San Francisco Cannabis Buyers Club, the first medical cannabis dispensary in the United States.

Oaksterdam is a cultural district on the north end of Downtown Oakland, California, where medical cannabis is available for purchase in cafés, clubs, and patient dispensaries. Oaksterdam is located between downtown proper, the Lakeside, and the financial district. It is roughly bordered by 14th Street on the southwest, Harrison Street on the southeast, 19th Street on the northeast, and Telegraph Avenue on the northwest. The name is a portmanteau of "Oakland" and "Amsterdam," due to the Dutch city's cannabis coffee shops and the drug policy of the Netherlands.

California Senate Bill 420 was a bill introduced by John Vasconcellos of the California State Senate, and subsequently passed by the California State Legislature and signed by Governor Gray Davis in 2003 "pursuant to the powers reserved to the State of California and its people under the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution." It clarified the scope and application of California Proposition 215, also known as the Compassionate Use Act of 1996, and established the California medical marijuana program. The bill's title is notable because "420" is a common phrase used in cannabis culture.

The San Francisco Cannabis Buyers Club was the first public medical cannabis dispensary in the United States. Gay rights and AIDS activists were responsible for its founding and the larger success of the buyers club movement in the 1990s. Historically, the buyers club model emerged partly in response to the global pandemic of HIV/AIDS, and the failure of the U.S. government to allow the gay community and people suffering from other illnesses such as cancer, to legally use cannabis as palliative medicine. The club operated intermittently in at least three separate locations from 1991 to 1998, when it was permanently closed.

Dennis Robert Peron was an American activist and businessman who became a leader in the movement for the legalization of cannabis throughout the 1990s. He influenced many in California and thus changed the political debate on marijuana in the United States.

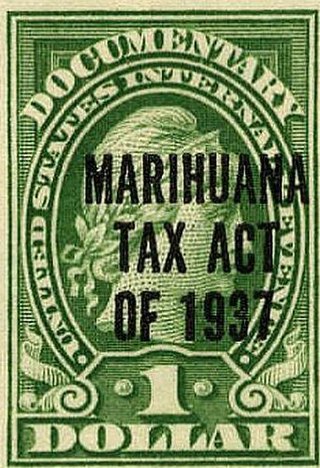

In the United States, increased restrictions and labeling of cannabis as a poison began in many states from 1906 onward, and outright prohibitions began in the 1920s. By the mid-1930s cannabis was regulated as a drug in every state, including 35 states that adopted the Uniform State Narcotic Drug Act. The first national regulation was the Marihuana Tax Act of 1937.

The use, sale, and possession of cannabis containing over 0.3% THC by dry weight in the United States, despite laws in many states permitting it under various circumstances, is illegal under federal law. As a Schedule I drug under the federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA) of 1970, cannabis containing over 0.3% THC by dry weight is considered to have "no accepted medical use" and a high potential for abuse and physical or psychological dependence. Cannabis use is illegal for any reason, with the exception of FDA-approved research programs. However, individual states have enacted legislation permitting exemptions for various uses, including medical, industrial, and recreational use.

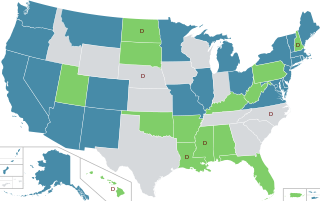

In the United States, the use of cannabis for medical purposes is legal in 38 states, four out of five permanently inhabited U.S. territories, and the District of Columbia, as of March 2023. Ten other states have more restrictive laws limiting THC content, for the purpose of allowing access to products that are rich in cannabidiol (CBD), a non-psychoactive component of cannabis. There is significant variation in medical cannabis laws from state to state, including how it is produced and distributed, how it can be consumed, and what medical conditions it can be used for.

Oaksterdam University is self-recognized as the world's first cannabis college. Located in Oakland, CA, the educational facility was founded in November 2007 by medical marijuana activist Richard Lee to offer quality training for the cannabis industry, with a mission to "legitimize the business and work to change the law to make cannabis legal." Its main campus was formerly located in Downtown Oakland, Calif. On March 8, 2020, fire damaged the Oaksterdam campus at which time the brick and mortar location closed. Classes are currently held online only, both asynchronous and in real time. The university has graduated nearly 50,000 students from more than 40 countries.

Cannabis in California has been legal for medical use since 1996, and for recreational use since late 2016. The state of California has been at the forefront of efforts to liberalize cannabis laws in the United States, beginning in 1972 with the nation's first ballot initiative attempting to legalize cannabis. Although it was unsuccessful, California would later become the first state to legalize medical cannabis through the Compassionate Use Act of 1996, which passed with 56% voter approval. In November 2016, California voters approved the Adult Use of Marijuana Act with 57% of the vote, which legalized the recreational use of cannabis.

Chris Bartkowicz is a state-licensed medical marijuana care-giver who was raided and arrested on the order of Denver area DEA agent Jeffrey Sweetin on February 12, 2010 after accepting an invitation by 9NEWS to do an interview about being a Colorado medical marijuana care-giver.

Conant v. Walters, 309 F.3d 629, is a legal case decided by the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which affirmed the right of physicians to recommend medical marijuana. The Court of Appeals affirmed the earlier decision of the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, which was filed under the caption Conant v. McCaffrey. Though the case involved chronic patients with untreatable diseases, the decision does not name these conditions as a prerequisite, nor does it limit drugs which may or may not be illegal.

Cannabis dispensaries in the United States or marijuana dispensaries are a type of cannabis retail outlet, local government-regulated physical location, typically inside a retail storefront or office building, in which a person can purchase cannabis and cannabis-related items for medical or recreational use.

Cannabis in Arizona is legal for recreational use. A 2020 initiative to legalize recreational use passed with 60% of the vote. Possession and cultivation of recreational cannabis became legal on November 30, 2020, with the first state-licensed sales occurring on January 22, 2021.

Cannabis in New Mexico is legal for recreational use as of June 29, 2021. A bill to legalize recreational use – House Bill 2, the Cannabis Regulation Act – was signed by Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham on April 12, 2021. The first licensed sales of recreational cannabis began on April 1, 2022.

Steve McWilliams was a medical marijuana activist from San Diego, California who protested the treatment of people under anti-cannabis laws. He committed suicide in 2005.

Scott Tracy Imler (1958-2018) was an American activist who advocated medical marijuana use in California. He worked with Dennis Peron, a fellow cannabis activist, during the movement for the legalization of marijuana in the 1990s. He was a co-author of Proposition 215 or the Compassionate Use Act of 1996, the law permitting medical marijuana in the state.

The Berkeley Patients Group (BPG) is the oldest continuously operating cannabis dispensary in the United States, inaugurated in 1999 in Berkeley, California. BPG has been known not only for cannabis dispensation, but also for its involvement in advocacy campaigns for cannabis policy reforms and the rights of patients using marijuana for medical purposes, and for its involvement with the scientific community.