United Kingdom

First World War

British war cabinet

Prior to the First World War, the British had the Committee of Imperial Defence. During World War I, it became a war committee. [1]

During the war, lengthy cabinet discussions came to be seen as a source of vacillation in Britain's war effort.

The number of cabinet ministries grew throughout the nineteenth century. Following dissatisfaction at the conduct of the Crimean War, Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli proposed that the number of cabinet members never exceed 10 (he had 12 at the time). However, this didn't happen, and the number of ministries continued to grow: 15 in 1859, 21 in 1914, and 23 in 1916. [2] Despite talk of "inner circles" within the Asquith Administration, all committees reported to the 23 cabinet ministers, whose priorities were diverse in nature, and who had final say over war policy formation for the first two years of World War I. This cumbersome arrangement could not stand; a more efficient way of prosecuting the war was needed.

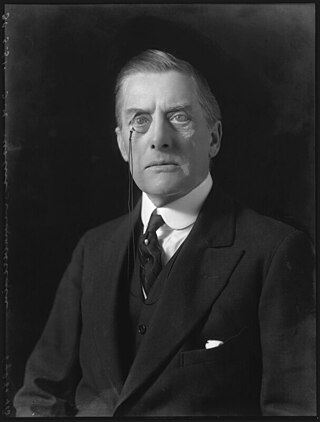

In December 1916 it was proposed that Prime Minister H. H. Asquith should delegate decision-making to a small, three-man committee chaired by the Secretary of State for War, David Lloyd George. Asquith initially agreed (provided the committee reported to him and he retained the right to attend if he chose) before changing his mind after being infuriated by a news story [3] in The Times which portrayed the proposed change as a defeat for him. The political crisis grew from this point until Asquith was forced to resign as Prime Minister; he was succeeded by Lloyd George who thereupon formed a small war cabinet. The original members of the war cabinet were: [4]

- David Lloyd George

- George Curzon (Lord President of the Council)

- Bonar Law (Chancellor of the Exchequer)

- Arthur Henderson (December 1916 – August 1917)

- Alfred Milner (December 1916 – April 1918)

Lloyd George, Curzon, and Bonar Law served throughout the existence of the war cabinet. Later members included:

- Jan Smuts (June 1917 – January 1919)

- George Barnes (May 1917 – January 1919)

- Edward Carson (July 1917 – January 1918)

- Austen Chamberlain (April 1918 – October 1919)

- Eric Geddes (January 1919 – October 1919)

Unlike a normal peacetime cabinet, few of these men had departmental responsibilities – Bonar Law, and then Chamberlain, served as chancellors of the exchequer, but the rest had no specific portfolio. The title of, "minister without portfolio" was important. It allowed total devotion to war duties, without the distraction of civil cabinet responsibilities. Among others, the Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour, was never a member of the war cabinet, nor were the service ministers Edward Stanley (Army) and Edward Carson (Navy). The latter did join, but only after leaving the Admiralty. [5] Whenever these specialties were needed by the war cabinet, they were summoned. The functioning of the war cabinet is best summed up by Lord Hutchison during a Parliamentary debate held on 14 March 1934. [6]

Despite its efficiency, on 8 June 1917 at Lord Milner's urging, it became necessary to form a War Policy Committee within the war cabinet to coordinate war strategy. Its members included David Lloyd George, Lord Milner, Lord Curzon, Jan Smuts, and Maurice Hankey. [7] [8] Upon his transfer from the war cabinet to the War Office as Secretary of State for War in April 1918, the X Committee was created so Lord Milner could meet with the Prime Minister before war cabinet sessions to continue the talks.

Previously, all cabinet members were paid based upon their cabinet status. With the creation of ministers without portfolio, it was suggested that these positions go unpaid. Indeed, Henry Petty-Lansdowne, a millionaire, while a member without portfolio in Asquith's government, received no pay. The debate, which took place in the House of Commons on 13 February 1917, was decided in the new government's favour. [9] Appropriations of £5,000 a year (£350,000 in 2020) were made. [10]

The British war cabinet marked the first time minutes were recorded of official meetings. [11] This innovation set the trend for all important corporate and governmental meetings since. [12]

With World War I over, and the two main peace treaties signed with Germany and Austria-Hungary, Lloyd George decided to discontinue the war cabinet. Its last meeting was held on 27 October 1919. [13] [14]

Imperial War Cabinet

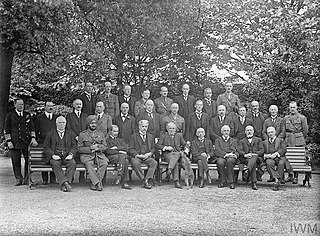

The origins of an Imperial War Cabinet date back to the beginning of Lloyd George's government, and the proper way of responding to peace offerings from Germany. The first mention of a conference in the war cabinet happened on 18 December 1916. [15] [16] In January invitations were sent out, and in the spring of 1917 the Imperial War Cabinet was formed. Goals were also established to strengthen imperial federation by upgrading the status of the Dominions and India to an equal footing with that of Britain when coordinating war strategy. The Imperial War Cabinet met in three sessions: from March to May 1917, [17] from June to August 1918, [18] and from August to December 1918. [19] The last session was improvised. It occurred due to Allied successes on the battlefield and a desire of dominion partners to keep abreast of events. Its original members were:

- Arthur Henderson (British war cabinet)

- Alfred Milner (British war cabinet)

- George Curzon (British war cabinet)

- Bonar Law (British war cabinet and future Prime Minister)

- David Lloyd George (British war cabinet and Prime Minister)

- Robert Borden (Prime Minister of Canada)

- W.F. Massey (Prime Minister of New Zealand)

- Jan Smuts (Minister for Defence, South Africa)

- S.P. Sinha (Representative of Bengal)

- Maharajah of Bikanir (King of (Northern) India)

- James Meston (Assistant to the Secretary of State for India, United Kingdom)

- Austen Chamberlain (Secretary of State for India, United Kingdom)

- Robert Cecil (Minister of Blockade, United Kingdom)

- Walter Long (Secretary of State for the Colonies, United Kingdom)

- Joseph Ward (Finance Minister of New Zealand)

- George Perley (Overseas War Minister of Canada)

- Robert Rogers (Minister of Public Works, Canada)

- J.D. Hazen (Minister of the Navy, Canada)

- Leopold Amery (Assistant Secretary from the United Kingdom)

- Admiral John Jellicoe (First Sea Lord, United Kingdom)

- Edward Carson (First Lord of the Admiralty (civilian head of the Royal Navy), United Kingdom)

- Edward Stanley (Secretary of State for War, United Kingdom)

- General Frederick Maurice (Director of Military Operations, United Kingdom)

- Maurice Hankey (Assistant Secretary from the United Kingdom)

- Henry Lambert (Colonial Office, from the United Kingdom)

- Major Lancelot Storr (Assistant Secretary from the United Kingdom)

To strengthen ties between countries, the writing of an imperial constitution was a significant priority in 1917. However, the delegates postponed the matter until after the war, and they failed to take it up.

Minutes to the Imperial War Cabinet meetings are held at the National Archives (Kew). [20]

Second World War

On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland and after to-ing and fro-ing with French Foreign Minister Georges Bonnet, an ultimatum was presented to the Germans and on its expiry war was declared at 11am on 3 September 1939.

Chamberlain war ministry

On 3 September 1939, Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain announced his war cabinet.

- Prime Minister: Neville Chamberlain (Conservative)

- Lord Privy Seal: Samuel Hoare (Conservative)

- Chancellor of the Exchequer: John Simon (National Liberal)

- Foreign Secretary: Edward Wood (Conservative)

- Secretary of State for War: Leslie Hore-Belisha (National Liberal)

- Secretary of State for Air: Kingsley Wood (Conservative)

- First Lord of the Admiralty: Winston Churchill (Conservative)

- Minister for the Coordination of Defence: Ernle Chatfield (National Government)

- Minister without Portfolio: Maurice Hankey (National Government)

Dominated largely by Conservative ministers who served under Chamberlain's National Government between 1937 and 1939, the additions of Lord Hankey (a former Cabinet Secretary from the First World War) and Winston Churchill (strong anti-appeaser) seemed to give the cabinet more balance. Unlike David Lloyd George's war cabinet, the members of this one were also heads of government departments.

In January 1940, after disagreements with the Chiefs of Staff, Hore-Belisha resigned from the National Government, refusing a move to the post of President of the Board of Trade. He was succeeded by Oliver Stanley.

It was originally the practice for the Chiefs of Staff to attend all military discussions of the Chamberlain war cabinet. Churchill became uneasy with this, as he felt that when they attended they did not confine their comments to purely military issues. To overcome this, a Military Co-ordination Committee was set up, consisting of the three service ministers normally chaired by Chatfield. This together with the service chiefs would co-ordinate the strategic ideas of 'top hats' and 'brass' and agree strategic proposals to put forward to the war cabinet. Unfortunately, except when chaired by the Prime Minister, the Military Co-ordinating Committee lacked sufficient authority to override a Minister "fighting his corner". When Churchill took over from Chatfield, whilst continuing to represent the Admiralty, this introduced additional problems, and did little to improve the pre-existing ones. Chamberlain announced a further change in arrangements in the Norway Debate, but this (and the Military Co-ordination Committee) was overtaken by events, the Churchill war cabinet being run on rather different principles. [21]

Churchill war ministry

When he became Prime Minister during the Second World War, Winston Churchill formed a war cabinet, initially consisting of the following members:

- Prime Minister & Minister of Defence: Winston Churchill (Conservative)

- Lord President of the Council: Neville Chamberlain (Conservative)

- Lord Privy Seal: Clement Attlee (Labour)

- Foreign Secretary: Edward Wood (Conservative)

- Minister without Portfolio: Arthur Greenwood (Labour)

Churchill strongly believed that the war cabinet should be kept to a relatively small number of individuals to allow efficient execution of the war effort. Even so, there were a number of ministers who, though they were not members of the war cabinet, were "Constant Attenders". [22] As the war cabinet considered issues that pertained to a given branch of the service or government due input was obtained from the respective body.

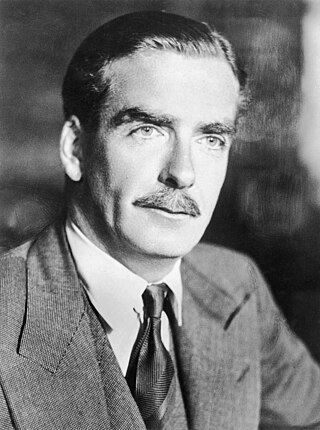

The War Cabinet would undergo a number of changes in composition over the next five years. On 19 February 1942 a reconstructed war cabinet was announced by Churchill consisting of the following members: [23]

- Prime Minister and Minister of Defence: Winston Churchill (Conservative)

- Deputy Prime Minister and Secretary of State for Dominions Affairs: Clement Attlee (Labour)

- Lord Privy Seal and Leader of the House of Commons: Stafford Cripps (Labour)

- Lord President of the Council: John Anderson (National)

- Foreign Secretary: Anthony Eden (Conservative)

- Minister of Production: Oliver Lyttelton (Conservative)

- Minister of Labour: Ernest Bevin (Labour)

This war cabinet was consistent with Churchill's view that members should also hold "responsible offices and not mere advisors at large with nothing to do but think and talk and take decisions by compromise or majority" [24] The war cabinet often met within the Cabinet War Rooms, particularly during The Blitz of London. [25]

Falklands War

- Prime Minister – Margaret Thatcher

- Deputy Prime Minister & Home Secretary – Willie Whitelaw

- Secretary of State for Foreign & Commonwealth Affairs – Francis Pym

- Secretary of State for Defence – John Nott

- Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster – Cecil Parkinson

- Chief of the Defence Staff – Admiral Terence Lewin

- Attorney General – Michael Havers

Thatcher chose not to include any representation of Her Majesty's Treasury on the advice of former Prime Minister Harold Macmillan (who had been British Minister Resident in the Mediterranean theatre for the second half of World War II), that the security and defence of the armed forces and the war effort should not be compromised for financial reasons. [26]

Persian Gulf War

- Prime Minister – John Major

- Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs – Douglas Hurd

- Secretary of State for Defence – Tom King

- Chancellor of the Exchequer – Norman Lamont

- Chief of the Defence Staff – Marshal of the RAF David Craig [27]

Invasion of Afghanistan

- Prime Minister – Tony Blair

- Deputy Prime Minister – John Prescott

- Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs – Jack Straw

- Secretary of State for Home Affairs – David Blunkett

- Secretary of State for Defence – Geoff Hoon

- Chancellor of the Exchequer – Gordon Brown

- Secretary of State for International Development – Clare Short

- Chief of the Defence Staff – Admiral Michael Boyce

- Downing Street Director of Communications – Alastair Campbell

- Leader of the House of Commons – Robin Cook [28]

Iraq War

- Prime Minister – Tony Blair

- Deputy Prime Minister – John Prescott

- Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs – Jack Straw

- Secretary of State for Home Affairs – David Blunkett

- Secretary of State for Defence – Geoff Hoon

- Chancellor of the Exchequer – Gordon Brown

- Secretary of State for International Development – Clare Short

- Chief of the Defence Staff – Admiral Michael Boyce

- Downing Street Director of Communications – Alastair Campbell

- Leader of the House of Commons – John Reid

- Director of MI5 – Eliza Manningham-Buller

- Director of MI6 – Richard Dearlove [29]