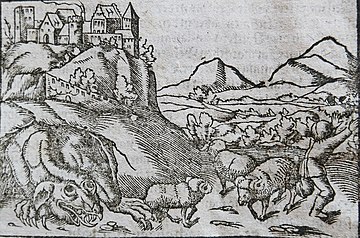

The European dragon is a legendary creature in folklore and mythology among the overlapping cultures of Europe.

Stanislaus of Szczepanów was Bishop of Kraków known chiefly for having been martyred by the Polish King Bolesław II the Generous. Stanislaus is venerated in the Roman Catholic Church as Saint Stanislaus the Martyr.

Abdank is a Polish coat of arms. It was used by several szlachta families in the times of the Kingdom of Poland and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Wincenty Kadłubek was a Polish Catholic prelate and professed Cistercian who served as the Bishop of Kraków from 1208 until his resignation in 1218. His episcopal mission was to reform the diocesan priests to ensure their holiness and invigorate the faithful and cultivate greater participation in ecclesial affairs on their part. Wincenty was much more than just a bishop; he was a leading scholar in Poland from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. He was also a lawyer, historian, church reformer, monk, magister, and the father of Polish culture and national identity.

The Wawel Royal Castle and the Wawel Hill on which it sits constitute the most historically and culturally significant site in Poland. A fortified residency on the Vistula River in Kraków, it was established on the orders of King Casimir III the Great and enlarged over the centuries into a number of structures around an Italian-styled courtyard. It represents nearly all European architectural styles of the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque periods.

Smocza Jama is a limestone cave in the Wawel Hill in Kraków. Owing to its location in the heart of the former Polish capital and its connection to the legendary Wawel Dragon, it is the best known cave in Poland.

The Battle of Hundsfeld or Battle of Psie Pole was said to be fought on 24 August 1109 near the Silesian capital Wrocław between the Holy Roman Empire in aid of the claims of the exiled Piast duke Zbigniew against his ruling half-brother, Bolesław III Wrymouth of Poland. It was recorded by the medieval Polish chronicler Bishop Wincenty Kadłubek of Kraków in his Chronica seu originale regum et principum Poloniae several decades later.

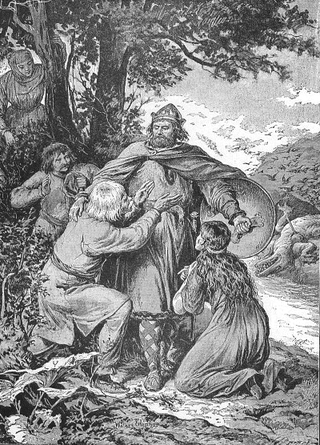

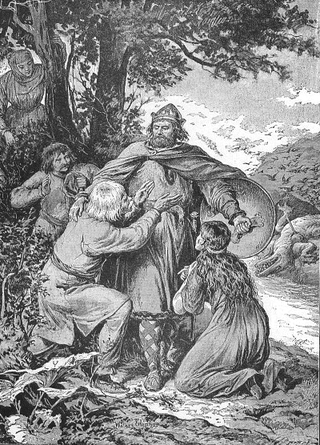

Krakus, Krak or Grakch was a legendary Polish prince, ruler of the Vistulans, and the presumed founder of Kraków. Krakus is also credited with building Wawel Castle and slaying the Wawel Dragon by feeding it a dead sheep full of sulfur. The latter is how Krak the cobbler became Krakus the prince, and later king. The first recorded mention of Krakus, then spelled Grakch, is in the Chronica seu originale regum et principum Poloniae from 1190.

The Gesta principum Polonorum is the oldest known medieval chronicle documenting the history of Poland from the legendary times until 1113. Written in Latin by an anonymous author, it was most likely completed between 1112 and 1118, and its extant text is present in three manuscripts with two distinct traditions. Its anonymous author is traditionally called Gallus, a foreigner and outcast from an unknown country, who travelled to the Kingdom of Poland via Hungary. Gesta was commissioned by Poland's then ruler, Boleslaus III Wrymouth; Gallus expected a prize for his work, which he most likely received and of which he lived the rest of his life.

Lechites, also known as the Lechitic tribes, is a name given to certain West Slavic tribes who inhabited modern-day Poland and eastern Germany, and were speakers of the Lechitic languages. Distinct from the Czech–Slovak subgroup, they are the closest ancestors of ethnic Poles and of Pomeranians, Lusatians and Polabians.

Chronica seu originale regum et principum Poloniae, short name Chronica Polonorum, is a Latin history of Poland written by Wincenty Kadłubek between 1190 and 1208 CE. The work was probably commissioned by Casimir II of Poland. Consisting of four books, it describes Polish history.

Princess Wanda Princess and the Queen, daughter of King Krakus, the founder of Krakow, Poland. Wanda was very famous for her outstanding beauty and wisdom. She was the daughter of the Lechitic King Krakus (Krak) legendary founder of Kraków. Upon her father's death, she became queen of the Lechites/Poles, but in the later reeditions committed suicide to avoid an unwanted marriage to a Teuton. In both versions of the source legend, she died childless. Wanda is also often known as the Virgin Queen.

Esterka (Estera) refers to a mythical Jewish mistress of Casimir the Great, the historical King of Poland who reigned between 1333 and 1370. Medieval Polish and Jewish chroniclers considered the legend as historical fact and report a wonderful love story between the beautiful Jewess and the great monarch.

Bolesław II the Bold, also known as the Generous was Duke of Poland from 1058 to 1076 and King of Poland from 1076 to 1079. He was the eldest son of Duke Casimir I the Restorer and Maria Dobroniega of Kiev.

The Wawel Chakra is a place on Wawel hill in Kraków in Poland which is believed to emanate powerful spiritual energy. Adherents believe it to be one of the world's main centers of spiritual energy. The Wawel Chakra is said to be one of a few select places of immense power on Earth, which, like a chakra point in the human body, allegedly functions as part of an (esoteric) energetic system within Earth.

Wawel Dragon Statue is a monument at the foot of the Wawel Hill in Kraków, Poland, in front of the Wawel Dragon's den, dedicated to the mythical Wawel Dragon. Installed in 1972, the statue is capable of breathing fire on demand.

The Wielkopolska Chronicle is an anonymous medieval chronicle describing supposed history of Poland from legendary times up to the year 1273. It was written in Latin at the end of the 13th or the beginning of the 14th century.

Krakus II was a mythological ruler of Poland. He was the successor of and son of the alleged founder of the City of Kraków, Krakus I, and he was the younger brother of Lech II, according to Wincenty Kadłubek. He ties the family to the national story of the dragon of Wawel. In this, their father Krak sent them to defeat the dragon, which they managed, after an unsuccessful battle, by stuffing the tribute animals with straw which suffocated the dragon. After this, Krak threw himself upon Lech and killed him, though their father pretended that the dragon was responsible. Eventually the story was found out, and Krak II was overthrown and replaced by his daughter Wanda.

Chronica Polonorum is a treatise about Polish history and geography written in Latin by a Polish renaissance scholar Maciej Miechowita, a professor of Jagiellonian University, historian, geographer, astrologer, and royal physician of king Sigismund I the Old. Chronica Polonorum was first published in 1519.

The Murder of Stanislaus of Szczepanów by the Polish king Bolesław II the Generous in 1079. He is said to have slain Stanislaus of Szczepanów while he was celebrating Mass in the Skałka outside the walls of Kraków.