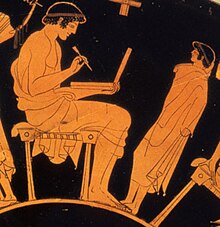

A diptych is any object with two flat plates which form a pair, often attached by a hinge. For example, the standard notebook and school exercise book of the ancient world was a diptych consisting of a pair of such plates that contained a recessed space filled with wax. Writing was accomplished by scratching the wax surface with a stylus. When the notes were no longer needed, the wax could be slightly heated and then smoothed to allow reuse. Ordinary versions had wooden frames, but more luxurious diptychs were crafted with more expensive materials.

The Kassites were people of the ancient Near East, who controlled Babylonia after the fall of the Old Babylonian Empire c. 1531 BC and until c. 1155 BC.

Hieratic is the name given to a cursive writing system used for Ancient Egyptian and the principal script used to write that language from its development in the third millennium BCE until the rise of Demotic in the mid-first millennium BCE. It was primarily written in ink with a reed brush on papyrus.

A stylus is a writing utensil or a small tool for some other form of marking or shaping, for example, in pottery. It can also be a computer accessory that is used to assist in navigating or providing more precision when using touchscreens. It usually refers to a narrow elongated staff, similar to a modern ballpoint pen. Many styluses are heavily curved to be held more easily. Another widely used writing tool is the stylus used by blind users in conjunction with the slate for punching out the dots in Braille.

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic writing system that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Near East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. Cuneiform scripts are marked by and named for the characteristic wedge-shaped impressions which form their signs. Cuneiform is the earliest known writing system and was originally developed to write the Sumerian language of southern Mesopotamia.

Hattusa, also Hattuşa, Ḫattuša, Hattusas, or Hattusha, was the capital of the Hittite Empire in the late Bronze Age during two distinct periods. Its ruins lie near modern Boğazkale, Turkey, within the great loop of the Kızılırmak River.

Nimrud is an ancient Assyrian city located in Iraq, 30 kilometres (20 mi) south of the city of Mosul, and 5 kilometres (3 mi) south of the village of Selamiyah, in the Nineveh Plains in Upper Mesopotamia. It was a major Assyrian city between approximately 1350 BC and 610 BC. The city is located in a strategic position 10 kilometres (6 mi) north of the point that the river Tigris meets its tributary the Great Zab. The city covered an area of 360 hectares. The ruins of the city were found within one kilometre (1,100 yd) of the modern-day Assyrian village of Noomanea in Nineveh Governorate, Iraq.

Assyriology, also known as Cuneiform studies or Ancient Near East studies, is the archaeological, anthropological, historical, and linguistic study of the cultures that used cuneiform writing. The field covers Pre Dynastic Mesopotamia, Sumer, the early Sumero-Akkadian city-states, the Akkadian Empire, Ebla, the Akkadian and Imperial Aramaic speaking states of Assyria, Babylonia and the Sealand Dynasty, the migrant foreign dynasties of southern Mesopotamia, including the Gutians, Amorites, Kassites, Arameans, Suteans and Chaldeans. Assyriology can be included to cover Neolithic pre-Dynastic cultures dating to as far back as 8000 BC through to the Islamic Conquest of the 7th century AD so the topic is significantly wider than that implied by the root "Assyria".

Aššur (; Sumerian: 𒀭𒊹𒆠 AN.ŠAR2KI, Assyrian cuneiform: Aš-šurKI, "City of God Aššur"; Syriac: ܐܫܘܪ Āšūr; Old Persian: 𐎠𐎰𐎢𐎼 Aθur, Persian: آشور Āšūr; Hebrew: אַשּׁוּר ʾAššūr, Arabic: اشور), also known as Ashur and Qal'at Sherqat, was the capital of the Old Assyrian city-state (2025–1364 BC), the Middle Assyrian Empire (1363–912 BC), and for a time, of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BC). The remains of the city lie on the western bank of the Tigris River, north of the confluence with its tributary, the Little Zab, in what is now Iraq, more precisely in the al-Shirqat District of the Saladin Governorate.

Ashur-nasir-pal II was king of Assyria from 883 to 859 BCE. Ashurnasirpal II succeeded his father, Tukulti-Ninurta II. His son and successor was Shalmaneser III and his queen was Mullissu-mukannišat-Ninua.

Borsippa or Birs Nimrud is an archeological site in Babil Governorate, Iraq. The ziggurat is today one of the most vividly identifiable surviving ones, identified in the later Arabic culture with the Tower of Babel due to Nebuchadnezzar referring to it as the Tower of Borsippa or tongue tower, as stated in the stele recovered on site in the 19th century. However, modern scholarship concludes that the Babylonian builders of the Ziggurat in reality erected it as a religious edifice in honour of the local god Nabu, called the "son" of Babylon's Marduk, as would be appropriate for Babylon's lesser sister-city.

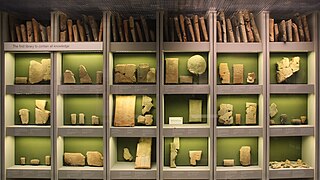

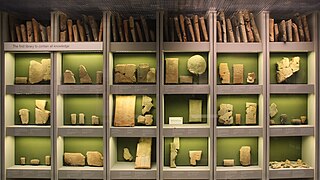

The Royal Library of Ashurbanipal, named after Ashurbanipal, the last great king of the Assyrian Empire, is a collection of more than 30,000 clay tablets and fragments containing texts of all kinds from the 7th century BCE, including texts in various languages. Among its holdings was the famous Epic of Gilgamesh.

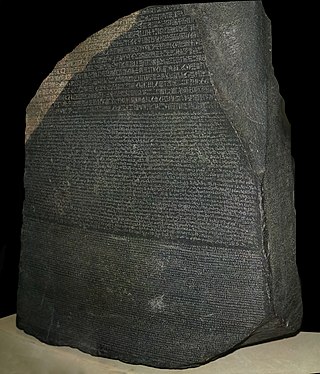

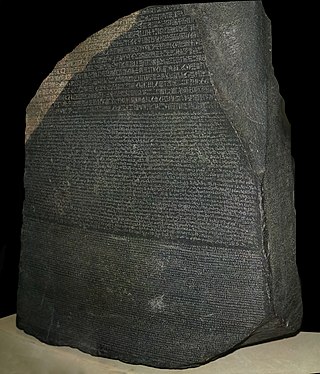

In epigraphy, a multilingual inscription is an inscription that includes the same text in two or more languages. A bilingual is an inscription that includes the same text in two languages. Multilingual inscriptions are important for the decipherment of ancient writing systems, and for the study of ancient languages with small or repetitive corpora.

The Department of the Middle East, numbering some 330,000 works, forms a significant part of the collections of the British Museum, and the world's largest collection of Mesopotamian antiquities outside Iraq. The collections represent the civilisations of the ancient Near East and its adjacent areas.

The Symmachi–Nicomachi diptych is a book-size Late Antique ivory diptych dating to the late fourth or early fifth century, whose panels depict scenes of ritual pagan religious practices. Both its style and its content reflect a short-lived revival of traditional Roman religion and Classicism at a time when the Roman world was turning towards Christianity and rejecting the Classical tradition.

The Poet and Muse diptych is a Late Antique ivory diptych that appears to commemorate, and to flatter, the literary pursuits of the aristocrat who commissioned it, so that it stands somewhat apart from the consular diptychs that were carved for distribution to friends and patrons when a man assumed the consular dignity during the later Roman Empire. The original inscription in this example, unusually, will have been carried out on the borders of the reverse side, which was infilled with a layer of wax for writing on, the ivory diptych being a very grand example of a wax tablet; the inscription has not survived, so there can be no way to identify the writer for whom it was made. In the literature that has accumulated about this diptych, various prominent figures have been offered as candidates: Ausonius, Boethius, and Claudian, and even earlier figures, like Ennius and Seneca, with whom the donor wished to be associated

The Nimrud ivories are a large group of small carved ivory plaques and figures dating from the 9th to the 7th centuries BC that were excavated from the Assyrian city of Nimrud during the 19th and 20th centuries. The ivories mostly originated outside Mesopotamia and are thought to have been made in the Levant and Egypt, and have frequently been attributed to the Phoenicians due to a number of the ivories containing Phoenician inscriptions. They are foundational artefacts in the study of Phoenician art, together with the Phoenician metal bowls, which were discovered at the same time but identified as Phoenician a few years earlier. However, both the bowls and the ivories pose a significant challenge as no examples of either – or any other artefacts with equivalent features – have been found in Phoenicia or other major colonies.

Stephanie Mary Dalley FSA is a British Assyriologist and scholar of the Ancient Near East. Prior to her retirement, she was a teaching Fellow at the Oriental Institute, Oxford. She is known for her publications of cuneiform texts and her investigation into the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, and her proposal that it was situated in Nineveh, and constructed during Sennacherib's rule.

Assyrian sculpture is the sculpture of the ancient Assyrian states, especially the Neo-Assyrian Empire of 911 to 612 BC, which was centered around the city of Assur in Mesopotamia which at its height, ruled over all of Mesopotamia, the Levant and Egypt, as well as portions of Anatolia, Arabia and modern-day Iran and Armenia. It forms a phase of the art of Mesopotamia, differing in particular because of its much greater use of stone and gypsum alabaster for large sculpture.

Iaba (also called Yaba), Banitu, and Atalia were queens of the Neo-Assyrian Empire as the primary consorts of the successive kings Tiglath-Pileser III, Shalmaneser V and Sargon II, respectively. Little is known of the lives of the three queens; they were not known by name by modern historians prior to the 1989 discovery of a stone sarcophagus among the Queens' tombs at Nimrud which contained objects inscribed with the names of all three women. The stone sarcophagus, believed to originally have been the tomb of Iaba since her name is on the nearby funerary inscription, presents a problem of identification as it contains objects with the names of three queens, but contains only two skeletons. The conventional interpretation is that the skeletons are those of Iaba and Atalia, but several alternate hypotheses have also been made, such as the idea that Iaba and Banitu could be the same person. Iaba and Banitu being the same person is however not supported by either historical or chronological evidence.