A crossbow is a ranged weapon using an elastic launching device consisting of a bow-like assembly called a prod, mounted horizontally on a main frame called a tiller, which is hand-held in a similar fashion to the stock of a long gun. Crossbows shoot arrow-like projectiles called bolts or quarrels. A person who shoots crossbow is called a crossbowman or an arbalist.

A watermill or water mill is a mill that uses hydropower. It is a structure that uses a water wheel or water turbine to drive a mechanical process such as milling (grinding), rolling, or hammering. Such processes are needed in the production of many material goods, including flour, lumber, paper, textiles, and many metal products. These watermills may comprise gristmills, sawmills, paper mills, textile mills, hammermills, trip hammering mills, rolling mills, wire drawing mills.

A water wheel is a machine for converting the energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a wheel, with a number of blades or buckets arranged on the outside rim forming the driving car. Water wheels were still in commercial use well into the 20th century, but they are no longer in common use today. Uses included milling flour in gristmills, grinding wood into pulp for papermaking, hammering wrought iron, machining, ore crushing and pounding fibre for use in the manufacture of cloth.

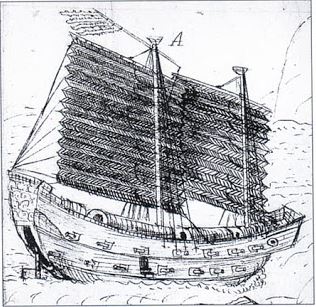

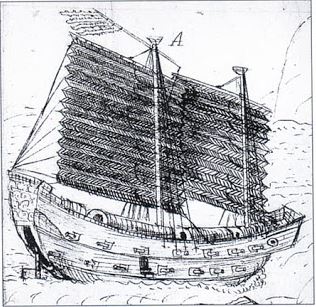

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, airship, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium. On an airplane, the rudder is used primarily to counter adverse yaw and p-factor and is not the primary control used to turn the airplane. A rudder operates by redirecting the fluid past the hull or fuselage, thus imparting a turning or yawing motion to the craft. In basic form, a rudder is a flat plane or sheet of material attached with hinges to the craft's stern, tail, or after end. Often rudders are shaped so as to minimize hydrodynamic or aerodynamic drag. On simple watercraft, a tiller—essentially, a stick or pole acting as a lever arm—may be attached to the top of the rudder to allow it to be turned by a helmsman. In larger vessels, cables, pushrods, or hydraulics may be used to link rudders to steering wheels. In typical aircraft, the rudder is operated by pedals via mechanical linkages or hydraulics.

A crane is a machine used to move materials both vertically and horizontally, utilizing a system of a boom, hoist, wire ropes or chains, and sheaves for lifting and relocating heavy objects within the swing of its boom. The device uses one or more simple machines, such as the lever and pulley, to create mechanical advantage to do its work. Cranes are commonly employed in transportation for the loading and unloading of freight, in construction for the movement of materials, and in manufacturing for the assembling of heavy equipment.

A crank is an arm attached at a right angle to a rotating shaft by which circular motion is imparted to or received from the shaft. When combined with a connecting rod, it can be used to convert circular motion into reciprocating motion, or vice versa. The arm may be a bent portion of the shaft, or a separate arm or disk attached to it. Attached to the end of the crank by a pivot is a rod, usually called a connecting rod (conrod).

The chain pump is type of a water pump in which several circular discs are positioned on an endless chain. One part of the chain dips into the water, and the chain runs through a tube, slightly bigger than the diameter of the discs. As the chain is drawn up the tube, water becomes trapped between the discs and is lifted to and discharged at the top. Chain pumps were used for centuries in the ancient Middle East, Europe, and China.

The repeating crossbow, also known as the repeater crossbow, and the Zhuge crossbow due to its association with the Three Kingdoms-era strategist Zhuge Liang (181–234 AD), is a crossbow invented during the Warring States period in China that combined the bow spanning, bolt placing, and shooting actions into one motion.

Medieval technology is the technology used in medieval Europe under Christian rule. After the Renaissance of the 12th century, medieval Europe saw a radical change in the rate of new inventions, innovations in the ways of managing traditional means of production, and economic growth. The period saw major technological advances, including the adoption of gunpowder, the invention of vertical windmills, spectacles, mechanical clocks, and greatly improved water mills, building techniques, and agriculture in general.

A trip hammer, also known as a tilt hammer or helve hammer, is a massive powered hammer. Traditional uses of trip hammers include pounding, decorticating and polishing of grain in agriculture. In mining, trip hammers were used for crushing metal ores into small pieces, although a stamp mill was more usual for this. In finery forges they were used for drawing out blooms made from wrought iron into more workable bar iron. They were also used for fabricating various articles of wrought iron, latten, steel and other metals.

A horse collar is a part of a horse harness that is used to distribute the load around a horse's neck and shoulders when pulling a wagon or plough. The collar often supports and pads a pair of curved metal or wooden pieces, called hames, to which the traces of the harness are attached. The collar allows the horse to use its full strength when pulling, essentially enabling the animal to push forward with its hindquarters into the collar. If wearing a yoke or a breastcollar, the horse had to pull with its less-powerful shoulders. The collar had another advantage over the yoke as it reduced pressure on the horse's windpipe.

Wang Zhen was a Chinese agronomist, inventor, mechanical engineer, politician, and writer of the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). He was one of the early innovators of the wooden movable type printing technology. His illustrated agricultural treatise was also one of the most advanced of its day, covering a wide range of equipment and technologies available in the late 13th and early 14th century.

The Song dynasty witnessed many substantial scientific and technological advances in Chinese history. Some of these advances and innovations were the products of talented statesmen and scholar-officials drafted by the government through imperial examinations. Shen Kuo (1031–1095), author of the Dream Pool Essays, is a prime example, an inventor and pioneering figure who introduced many new advances in Chinese astronomy and mathematics, establishing the concept of true north in the first known experiments with the magnetic compass. However, commoner craftsmen such as Bi Sheng (972–1051), the inventor of movable type printing, were also heavily involved in technical innovations.

It is not clear where and when the crossbow originated, but it is believed to have appeared in China and Europe around the 7th to 5th centuries BC. In China the crossbow was one of the primary military weapons from the Warring States period until the end of the Han dynasty, when armies were composed of up to 30 to 50 percent crossbowmen. The crossbow lost much of its popularity after the fall of the Han dynasty, likely due to the rise of the more resilient heavy cavalry during the Six Dynasties. One Tang dynasty source recommends a bow to crossbow ratio of five to one as well as the utilization of the countermarch to make up for the crossbow's lack of speed. The crossbow countermarch technique was further refined in the Song dynasty, but crossbow usage in the military continued to decline after the Mongol conquest of China. Although the crossbow never regained the prominence it once had under the Han, it was never completely phased out either. Even as late as the 17th century AD, military theorists were still recommending it for wider military adoption, but production had already shifted in favour of firearms and traditional composite bows.

The Han dynasty of early imperial China, divided between the eras of Western Han, the Xin dynasty of Wang Mang, and Eastern Han, witnessed some of the most significant advancements in premodern Chinese science and technology.

A treadwheel crane is a wooden, human powered hoisting and lowering device. It was primarily used during the Roman period and the Middle Ages in the building of castles and cathedrals. The often heavy charge is lifted as the individual inside the treadwheel crane walks. The rope attached to a pulley is turned onto a spindle by the rotation of the wheel thus allowing the device to hoist or lower the affixed pallet.

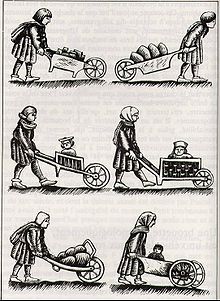

The handbarrow, also spelled hand-barrow and hand barrow, is a type of human-powered transport. It was originally a flat, rectangular frame used to carry loads such as salt cod, cheese and guano. It has handles on both ends, so two people are needed to use it. In Dutch cheese markets, official porters (kaasdragers) still use traditional barrows, albeit with straps, to transport cheese. A special handbarrow was built to move the Stone of Destiny around Westminster Abbey. Modern usage has expanded the definition to include the wheelbarrow or any wheeled cart or box propelled by hand.

Huo Che or rocket carts are several types of Chinese multiple rocket launcher developed for firing multiple fire arrows. The name Huo Che first appears in Feng Tian Jing Nan Ji, a historical text covering the Jingnan War of Ming dynasty.

The Ming dynasty continued to improve on gunpowder weapons from the Yuan and Song dynasties as part of its military. During the early Ming period larger and more cannons were used in warfare. In the early 16th century Turkish and Portuguese breech-loading swivel guns and matchlock firearms were incorporated into the Ming arsenal. In the 17th century Dutch culverin were incorporated as well and became known as hongyipao. At the very end of the Ming dynasty, around 1642, Chinese combined European cannon designs with indigenous casting methods to create composite metal cannons that exemplified the best attributes of both iron and bronze cannons. While firearms never completely displaced the bow and arrow, by the end of the 16th century more firearms than bows were being ordered for production by the government, and no crossbows were mentioned at all.