Printmaking is the process of creating artworks by printing, normally on paper, but also on fabric, wood, metal, and other surfaces. "Traditional printmaking" normally covers only the process of creating prints using a hand processed technique, rather than a photographic reproduction of a visual artwork which would be printed using an electronic machine ; however, there is some cross-over between traditional and digital printmaking, including risograph.

Invisible ink, also known as security ink or sympathetic ink, is a substance used for writing, which is invisible either on application or soon thereafter, and can later be made visible by some means, such as heat or ultraviolet light. Invisible ink is one form of steganography.

A blueprint is a reproduction of a technical drawing or engineering drawing using a contact print process on light-sensitive sheets introduced by Sir John Herschel in 1842. The process allowed rapid and accurate production of an unlimited number of copies. It was widely used for over a century for the reproduction of specification drawings used in construction and industry. Blueprints were characterized by white lines on a blue background, a negative of the original. Color or shades of grey could not be reproduced.

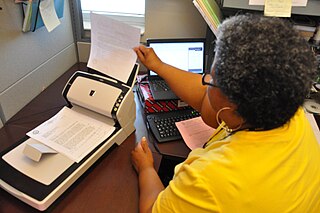

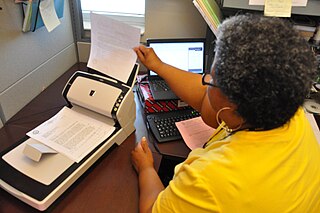

Reprography is the reproduction of graphics through mechanical or electrical means, such as photography or xerography. Reprography is commonly used in catalogs and archives, as well as in the architectural, engineering, and construction industries.

A spirit duplicator is a printing method invented in 1923 by Wilhelm Ritzerfeld that was commonly used for much of the rest of the 20th century. The term "spirit duplicator" refers to the alcohols that were a major component of the solvents used as "inks" in these machines. The device coexisted alongside the mimeograph.

The albumen print, also called albumen silver print, was published in January 1847 by Louis Désiré Blanquart-Evrard, and was the first commercially exploitable method of producing a photographic print on a paper base from a negative. It used the albumen found in egg whites to bind the photographic chemicals to the paper and became the dominant form of photographic positives from 1855 to the start of the 20th century, with a peak in the 1860–90 period. During the mid-19th century, the carte de visite became one of the more popular uses of the albumen method. In the 19th century, E. & H. T. Anthony & Company were the largest makers and distributors of albumen photographic prints and paper in the United States.

Offset printing is a common printing technique in which the inked image is transferred from a plate to a rubber blanket and then to the printing surface. When used in combination with the lithographic process, which is based on the repulsion of oil and water, the offset technique employs a flat (planographic) image carrier. Ink rollers transfer ink to the image areas of the image carrier, while a water roller applies a water-based film to the non-image areas.

Blue Line or Blueline may refer to:

Photoengraving is a process that uses a light-sensitive photoresist applied to the surface to be engraved to create a mask that protects some areas during a subsequent operation which etches, dissolves, or otherwise removes some or all of the material from the unshielded areas of a substrate. Normally applied to metal, it can also be used on glass, plastic and other materials.

Ozalid is a registered trademark of a type of paper used for "test prints" in the monochrome classic offset process. The word "Ozalid" is an anagram of "diazol", the name of the substance that the company "Ozalid" used in the fabrication of this type of paper.

Microforms are scaled-down reproductions of documents, typically either films or paper, made for the purposes of transmission, storage, reading, and printing. Microform images are commonly reduced to about 4% or 1⁄25 of the original document size. For special purposes, greater optical reductions may be used.

Thermo-Fax is 3M's trademarked name for a photocopying technology which was introduced in 1950. It was a form of thermographic printing and an example of a dry silver process. It was a significant advance as no chemicals were required, other than those contained in the copy paper itself. A thin sheet of heat sensitive copy paper was placed on the original document to be copied, and exposed to infrared energy. Wherever the image on the original paper contained carbon, the image absorbed the infrared energy when heated. The heated image then transferred the heat to the heat sensitive paper producing a blackened copy image of the original.

Canon Production Printing, formerly known as Océ until the end of 2019, is a Netherlands-based subset of Canon that develops, manufactures and sells printing and copying hardware and related software. The product line includes office printing and copying machinery, production printers, and wide-format printers for both technical documentation and color display graphics.

Architectural reprography, the reprography of architectural drawings, covers a variety of technologies, media, and supports typically used to make multiple copies of original technical drawings and related records created by architects, landscape architects, engineers, surveyors, mapmakers and other professionals in building and engineering trades.

The salt print was the dominant paper-based photographic process for producing positive prints from 1839 until approximately 1860.

Vesicular film, almost universally known as Kalvar, is a type of photographic film that is sensitive only to ultraviolet light and developed simply by heating the exposed film.

A heliographic copier or heliographic duplicator is an apparatus used in the world of reprography for making contact prints on paper from original drawings made with that purpose on tracing paper, parchment paper or any other transparent or translucent material using different procedures. In general terms some type of heliographic copier is used for making: Hectographic prints, Ferrogallic prints, Gel-lithographs or Silver halide prints. All of them, until a certain size, can be achieved using a contact printer with an appropriate lamp but for big engineering and architectural plans, the heliographic copiers used with the cyanotype and the diazotype technologies, are of the roller type, which makes them completely different from contact printers.

A contact copier, is a device used to copy an image by illuminating a film negative with the image in direct contact with a photosensitive surface. The more common processes are negative, where clear areas in the original produce an opaque or hardened photosensitive surface, but positive processes are available. The light source is usually an actinic bulb internal or external to the device

IBM manufactured and sold microfilm products from 1963 till 1969. It is an example of IBM attempting to enter an established market on the basis of a significant technical breakthrough.