A reform school was a penal institution, generally for teenagers mainly operating between 1830 and 1900. In the United Kingdom and its colonies reformatories commonly called reform schools were set up from 1854 onwards for youngsters who were convicted of a crime as an alternative to an adult prison. In parallel, "Industrial schools" were set up for vagrants and children needing protection. Both were 'certified' by the government from 1857, and in 1932 the systems merged and both were 'approved' and became approved schools.

A reformatory or reformatory school is a youth detention center or an adult correctional facility popular during the late 19th and early 20th centuries in Western countries. In the United Kingdom and United States, they came out of social concerns about cities, poverty, immigration, and gender following industrialization, as well as from a shift in penology to reforming instead of punishing the criminal. They were traditionally single-sex institutions that relied on education, vocational training, and removal from the city. Although their use declined throughout the 20th century, their impact can be seen in practices like the United States' continued implementation of parole and the indeterminate sentence.

The Tennessee Department of Correction (TDOC) is a Cabinet-level agency within the Tennessee state government responsible for the oversight of more than 20,000 convicted offenders in Tennessee's fourteen prisons, three of which are privately managed by the Corrections Corporation of America. The department is headed by the Tennessee Commissioner of Correction, who is currently Tony Parker. TDOC facilities' medical and mental health services are provided by Corizon. Juvenile offenders not sentenced as adults are supervised by the independent Tennessee Department of Children's Services, while inmates granted parole or sentenced to probation are overseen by the Department of Correction (TDOC)/Department of Parole. The agency is fully accredited by the American Correctional Association. The department has its headquarters on the sixth floor of the Rachel Jackson Building in Nashville.

The administrative divisions of Wisconsin include counties, cities, villages and towns. In Wisconsin, all of these are units of general-purpose local government. There are also a number of special-purpose districts formed to handle regional concerns, such as school districts.

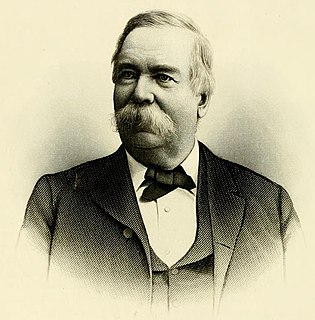

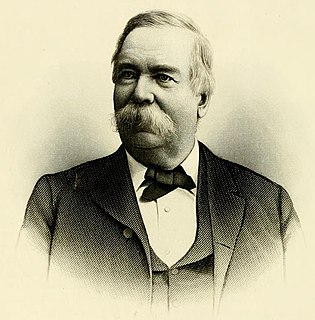

William Pitt Lynde was an American lawyer and politician from Wisconsin who served in the United States House of Representatives and as Mayor of Milwaukee.

A protectory was a Roman Catholic institution for the shelter and training of the young, designed to afford neglected or abandoned children shelter, food, raiment and the rudiments of an education in religion, morals, science and manual training or industrial pursuits.

The Oklahoma State Reformatory is a medium-security facility with some maximum and minimum-security housing for adult male inmates. Located off of State Highway 9 in Granite, Oklahoma, the 10-acre (4.0 ha) facility has a maximum capacity of 1042 inmates. The medium-security area accommodates 799 prisoners, minimum-security area houses roughly 200, and the maximum-security area with about 43 inmates. The prison currently houses approximately 975 prisoners. The prison was established by an act of the legislature in 1909 and constructed through prison labor, housing its first inmate in 1910. The facility is well known for the significant roles women played in its foundation and governance, most notably having the first female warden administer an all-male prison in the nation.

Oregon School for the Deaf (OSD) is a state school in Salem, Oregon, United States. It serves deaf and hard of hearing students from kindergarten through high school, and up to 18 years of age.

Mendota Mental Health Institute (MMHI) is a public psychiatric hospital in Madison, Wisconsin, United States, operated by the Wisconsin Department of Health Services. The hospital is accredited by the Joint Commission. Portions of the facility are included in the Wisconsin Memorial Hospital Historic District, District #88002183. The Mendota State Hospital Mound Group and Farwell's Point Mound Group are also located at the facility.

The Fairview Training Center was a state-run facility for people with developmental disabilities in Salem, Oregon, United States. Fairview was established in 1907 as the State Institution for the Feeble-Minded. The hospital opened on December 1, 1908, with 39 patients transferred from the Oregon State Hospital for the Insane. Before its closure in 2000, Fairview was administered by the Oregon Department of Human Services (DHS). DHS continued to operate the Eastern Oregon State Hospital in Pendleton until October 31, 2009.

Hillcrest Youth Correctional Facility was a state-run juvenile correctional facility located in Salem, Oregon, United States, established in 1914. Hillcrest was run by the Oregon Youth Authority (OYA), Oregon's juvenile corrections agency. It was closed on September 1, 2017, and all youth, staff, and programs were moved to MacLaren Youth Correctional Facility in Woodburn as part of a major project to consolidate the two facilities.

The Illinois Soldiers' and Sailors' Children's School, founded by the State of Illinois as Illinois Soldiers' Orphans' Home (ISOH) for orphans of the Civil War, was a children's home located in Normal from 1865 until 1979.

The Wisconsin Department of Children and Families (DCF) is an agency of the Wisconsin state government responsible for providing services to assist children and families and to oversee county offices handling those services. This includes child protective services, adoption and foster care services, and juvenile justice services. It also manages the licensing and regulation of facilities involved in the foster care and day care systems, performs background investigations of child care providers, and investigates incidents of potential child abuse or neglect. It administers the Wisconsin Works (W-2) program, the child care subsidy program, child support enforcement and paternity establishment services, and programs related to the federal Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) income support program.

The Mimico Correctional Centre was a provincial medium-security correctional facility for adult male inmates serving a sentence of 2-years-less-a-day or less in Ontario, Canada. Its history can be traced back to 1887. The Mimico Correctional Centre is one of several facilities operated by the Ministry of Community Safety and Correctional Services and was located at 130 Horner Avenue in the district of Etobicoke which is now a part of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. The facility was closed in 2011 and demolished to make room for the new Toronto South Detention Centre which opened in 2014.

The Magill Youth Training Centre, also known as the Boys Reformatory, McNally Training Centre and South Australian Youth Training Centre (SAYTC) since its founding in 1869, was the last iteration of a series of reformatories or youth detention centres in Woodforde, South Australia. The centre came under criticism in the 2000s for "barbaric" and "degrading" conditions and was replaced by a new 60-bed youth training centre at Cavan in 2012.

Michigan's State Public School at Coldwater was a model institution at Coldwater, Michigan, for the education and support of dependent and ill-treated children of the state. It was established by an act of the state legislature in 1871, but was not formally opened until 1874. The object of the institution was to receive, care for, educate, and place whenever possible in family homes all the dependent children of Michigan of sound mind and body between the ages of two and twelve. The board of control, however, had the discretionary power vested in it of admitting children under two where circumstances warranted such an exception.

The Park Ridge Youth Campus, or just The Youth Campus, was a school and orphanage in Park Ridge, Illinois from 1908 to 2012. The campus is on the National Register of Historic Places as the Illinois Industrial School for Girls, and was also known as the Park Ridge School for Girls. The campus is now Prospect Park and owned by the Park Ridge Park District.

Amanda L. Aikens was an American editor and philanthropist. During the civil war, she was one of the noted women workers, and it was through her public appeals that the question of the national soldiers' homes was agitated. She raised money in Wisconsin for the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore for the purpose of having women admitted on equal terms with men. She took an active interest in all charity and educational work in her state. Aikens was instrumental in founding the Wisconsin Industrial School for Girls, and was a member of the Humane Society, the Woman's Club, and the Athenaeum. In 1887, she began to edit the "Woman's World" section in her husband's paper, the Evening Wisconsin.

Jessie Donaldson Hodder was a women's prison reformer.

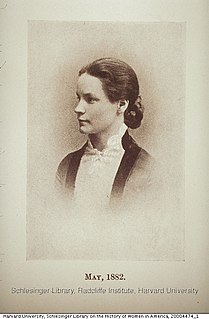

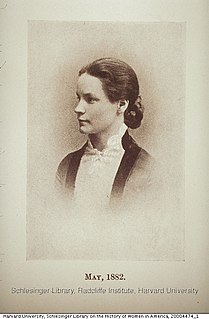

Mary Blanchard Lynde was an American philanthropist and social reformer, active in all of the progressive women's movements in Wisconsin. She was the co-founder of the Wisconsin Industrial School for Girls, and the first woman in Wisconsin to receive a state office appointment.