The Ku Klux Klan, commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is the name of several historical and current American white supremacist, far-right terrorist organizations and hate groups. The Klan was "the first organized terror movement in American history." Their primary targets are African Americans, Hispanics, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, Italian Americans, Irish Americans, and Catholics, as well as immigrants, leftists, homosexuals, Muslims, atheists, and abortion providers.

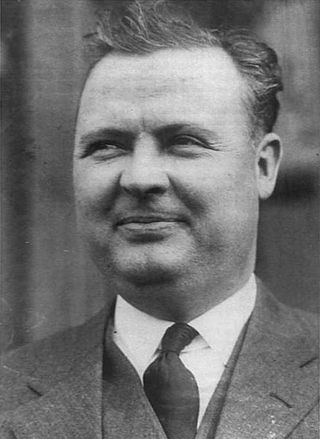

David Curtis "Steve" Stephenson was an American Ku Klux Klan leader, convicted rapist and murderer. In 1923 he was appointed Grand Dragon of the Indiana Klan and head of Klan recruiting for seven other states. Later that year, he led those groups to independence from the national KKK organization. Amassing wealth and political power in Indiana politics, he was one of the most prominent national Klan leaders. He had close relationships with numerous Indiana politicians, especially Governor Edward L. Jackson.

A Kleagle is an officer of the Ku Klux Klan whose main role is to recruit new members and must maintain the three guiding principles: recruit, maintain control, and safeguard.

This is a partial list of notable historical figures in U.S. national politics who were members of the Ku Klux Klan before taking office. Membership of the Klan is secret. Political opponents sometimes allege that a person was a member of the Klan, or was supported at the polls by Klan members.

Hiram Wesley Evans was the Imperial Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, an American white supremacist group, from 1922 to his death in 1939. A native of Alabama, Evans attended Vanderbilt University and became a dentist. He operated a small, moderately successful practice in Texas until 1920, when he joined the Klan's Dallas chapter. He quickly rose through the ranks and was part of a group that ousted William Joseph Simmons from the position of Imperial Wizard, the national leader, in November 1922. Evans succeeded him and sought to transform the group into a political power.

Daisy Douglas Barr was Imperial Empress (leader) of the Indiana Women's Ku Klux Klan (WKKK) in the early 1920s and an active member of the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). People were associated with both the KKK and the WCTU because the Ku Klux Klan was a very strong supporter and defender of temperance and National Prohibition. Professionally, she was a Quaker minister in two prominent churches, First Friends Church of New Castle, Indiana, and Friends Memorial Church in Muncie, Indiana. She served as the vice-chair of the Republican Committee in Indiana as well as president of the Indiana War Mother's organization. She was killed in a car wreck and her funeral was held in a Friends meeting.

Ku Klux Klan auxiliaries are organized groups that supplement, but do not directly integrate with the Ku Klux Klan. These auxiliaries include: Women of the Ku Klux Klan, The Jr. Ku Klux Klan, The Tri-K Girls, the American Crusaders, The Royal Riders of the Red Robe, The Ku Klux balla, and the Klan's Colored Man auxiliary.

Alma Bridwell White was the founder and a bishop of the Pillar of Fire Church. In 1918, she became the first woman bishop of Pillar of Fire in the United States. She was a proponent of feminism. She also associated herself with the Ku Klux Klan and was involved in anti-Catholicism, antisemitism, anti-Pentecostalism, racism, and hostility to immigrants. By the time of her death at age 84, she had expanded the sect to "4,000 followers, 61 churches, seven schools, ten periodicals and two broadcasting stations."

The Pillar of Fire International, also known as the Pillar of Fire Church, is a Methodist Christian denomination with headquarters in Zarephath, New Jersey. The Pillar of Fire Church affirms the Methodist Articles of Religion and as of 1988, had 76 congregations around the world, including the United States, as well as "Great Britain, India, Liberia, Malawi, Nigeria, the Philippines, Spain, and former Yugoslavia."

Kathleen Marie Blee is an American sociologist. She is a Distinguished Professor of Sociology at the University of Pittsburgh. Her areas of interest include gender, race and racism, social movements, and sociology of space and place. Special interests include how gender influences racist movements, including work on women in the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s.

Heroes of the Fiery Cross is a book in praise of the Ku Klux Klan, published in 1928 by Protestant Bishop Alma Bridwell White, in which she "sounds the alarm about imagined threats to Protestant Americans from Catholics and Jews", according to author Peter Knight. In the book she asks rhetorically, "Who are the enemies of the Klan? They are the bootleggers, law-breakers, corrupt politicians, weak-kneed Protestant church members, white slavers, toe-kissers, wafer-worshippers, and every spineless character who takes the path of least resistance." She also argues that Catholics are removing the Bible from public schools. Another topic is her anti-Catholic stance towards the United States presidential election of 1928, in which Catholic Al Smith was running for president.

The Indiana Klan was a branch of the Ku Klux Klan, a secret society in the United States that organized in 1915 to promote ideas of racial superiority and affect public affairs on issues of Prohibition, education, political corruption, and morality. It was strongly white supremacist against African Americans, Chinese Americans, and also Catholics and Jews, whose faiths were commonly associated with Irish, Italian, Balkan, and Slavic immigrants and their descendants. In Indiana, the Klan did not tend to practice overt violence but used intimidation in certain cases, whereas nationally the organization practiced illegal acts against minority ethnic and religious groups.

The Good Citizen was a sixteen-page monthly political periodical edited by Bishop Alma White and illustrated by Reverend Branford Clarke. The Good Citizen was published from 1913 until 1933 by the Pillar of Fire Church at their headquarters in Zarephath, New Jersey in the United States. White used the publication to expose "political Romanism in its efforts to gain the ascendancy in the U.S."

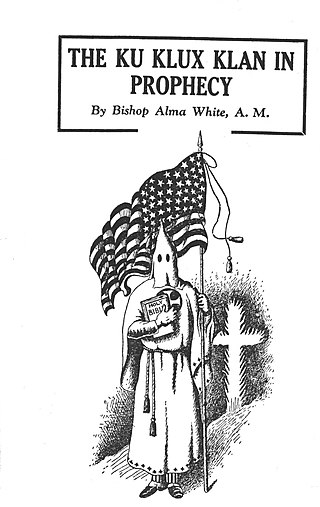

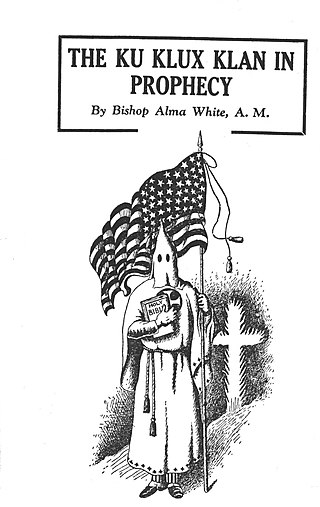

The Ku Klux Klan in Prophecy is a 144-page book written by Bishop Alma Bridwell White in 1925 and illustrated by Reverend Branford Clarke. In the book she uses scripture to rationalize that the Ku Klux Klan is sanctioned by God "through divine illumination and prophetic vision". She also believed that the Apostles and the Good Samaritan were members of the Klan. The book was published by the Pillar of Fire Church, which she founded, at their press in Zarephath, New Jersey. The book sold over 45,000 copies.

Ku Klux Klan recruitment of members is the responsibility of 'Kleagles', as defined by "Ku Klux Klan: An Encyclopedia". They are organizers or recruiters, "appointed by an imperial wizard or his imperial representative to 'sex' the KKK among non-members". These members were paid 200 dollars per hour by the commission and received a portion of each new member's invitation fee. Recruitment of new KKK members entailed framing economic, political, and social structural changes in favour of and in line with KKK goals. These goals promoted "100 per cent Americanism" and benefits for white native-born Protestants. Informal ways Klansmen recruited members included "with eligible co-workers and personal friends and try to enlist them". Protestant teachers were also targeted for Klan membership.

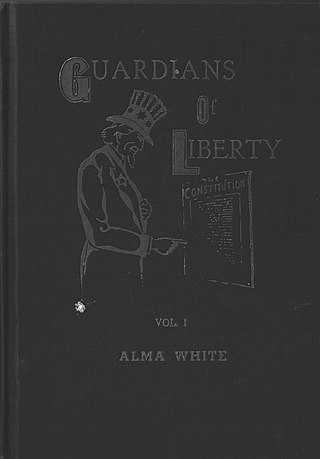

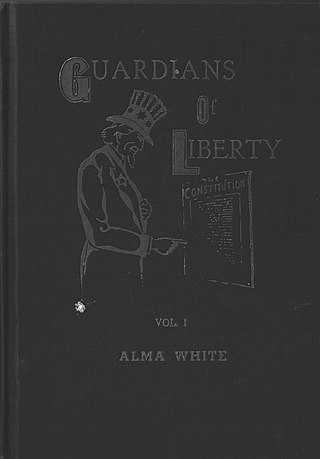

Guardians of Liberty is a three volume set of books published in 1943 by Bishop Alma Bridwell White, author of over 35 books and founder of the Pillar of Fire Church. Guardians of Liberty is primarily devoted to summarizing White's vehement anti-Catholicism under the guise of patriotism. White also defends her historical support of and association with the Ku Klux Klan while significantly but not completely distancing herself from the Klan. Each of the three volumes corresponds to one of the three books White published in the 1920s promoting the Ku Klux Klan and her political views which in addition to anti-Catholicism also included nativism, anti-Semitism and white supremacy. In Guardians of Liberty, White removed most, but not all of the direct references to the Klan that had existed in her three 1920s books, both in the text and in the illustrations. In Volumes I and II, she removed most of the nativist, anti-Semitic and white supremacist ideology that had appeared in her predecessor books. However, in Guardians Volume III, she did retain edited versions of chapters promoting nativism, anti-Semitism and white supremacy.

The National Knights of the Ku Klux Klan is a Klan faction that has been in existence since November 1963. In the sixties, the National Knights were the main competitors against Robert Shelton's United Klans of America.

The Ku Klux Klan is an organization that expanded operations into Canada, based on the second Ku Klux Klan established in the United States in 1915. It operated as a fraternity, with chapters established in parts of Canada throughout the 1920s and early 1930s. The first registered provincial chapter was registered in Toronto in 1925 by two Americans and a Canadian. The organization was most successful in Saskatchewan, where it briefly influenced political activity and whose membership included a member of Parliament, Walter Davy Cowan.

The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) arrived in the U.S. state of Oregon in the early 1920s, during the history of the second Klan, and it quickly spread throughout the state, aided by a mostly white, Protestant population as well as by racist and anti-immigrant sentiments which were already embedded in the region. The Klan succeeded in electing its members in local and state governments, which allowed it to pass legislation that furthered its agenda. Ultimately, the struggles and decline of the Klan in Oregon coincided with the struggles and decline of the Klan in other states, and its activity faded in the 1930s.

Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s is a non-fiction book written by Kathleen M. Blee and published by the University of California Press, Berkeley, in 1991.