Benzoic acid is a white (or colorless) solid with the formula C6H5CO2H. It is the simplest aromatic carboxylic acid. The name is derived from gum benzoin, which was for a long time its only source. Benzoic acid occurs naturally in many plants and serves as an intermediate in the biosynthesis of many secondary metabolites. Salts of benzoic acid are used as food preservatives. Benzoic acid is an important precursor for the industrial synthesis of many other organic substances. The salts and esters of benzoic acid are known as benzoates.

Yeasts are eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms classified as members of the fungus kingdom. The first yeast originated hundreds of millions of years ago, and at least 1,500 species are currently recognized. They are estimated to constitute 1% of all described fungal species.

Sourdough is a bread made by the fermentation of dough using wild lactobacillaceae and yeast. Lactic acid from fermentation imparts a sour taste and improves keeping qualities.

Malolactic conversion is a process in winemaking in which tart-tasting malic acid, naturally present in grape must, is converted to softer-tasting lactic acid. Malolactic fermentation is most often performed as a secondary fermentation shortly after the end of the primary fermentation, but can sometimes run concurrently with it. The process is standard for most red wine production and common for some white grape varieties such as Chardonnay, where it can impart a "buttery" flavor from diacetyl, a byproduct of the reaction.

A wine fault or defect is an unpleasant characteristic of a wine often resulting from poor winemaking practices or storage conditions, and leading to wine spoilage. Many of the compounds that cause wine faults are already naturally present in wine but at insufficient concentrations to be of issue. In fact, depending on perception, these concentrations may impart positive characters to the wine. However, when the concentration of these compounds greatly exceeds the sensory threshold, they replace or obscure the flavors and aromas that the wine should be expressing. Ultimately the quality of the wine is reduced, making it less appealing and sometimes undrinkable.

Lactobacillales are an order of gram-positive, low-GC, acid-tolerant, generally nonsporulating, nonrespiring, either rod-shaped (bacilli) or spherical (cocci) bacteria that share common metabolic and physiological characteristics. These bacteria, usually found in decomposing plants and milk products, produce lactic acid as the major metabolic end product of carbohydrate fermentation, giving them the common name lactic acid bacteria (LAB).

Dimethyl dicarbonate (DMDC) is an organic compound which is a colorless liquid with a pungent odor at high concentration at room temperature. It is primarily used as a beverage preservative, processing aid, or sterilant, and acts by inhibiting the enzymes acetate kinase and L-glutamic acid decarboxylase. It has also been proposed that DMDC inhibits the enzymes alcohol dehydrogenase and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase by causing the methoxycarbonylation of their histidine components.

Zygosaccharomyces bailii is a species in the genus Zygosaccharomyces. It was initially described as Saccharomyces bailii by Lindner in 1895, but in 1983 it was reclassified as Zygosaccharomyces bailii in the work by Barnett et al.

Leuconostoc mesenteroides is a species of lactic acid bacteria associated with fermentation, under conditions of salinity and low temperatures. In some cases of vegetable and food storage, it was associated with pathogenicity. L. mesenteroides is approximately 0.5-0.7 µm in diameter and has a length of 0.7-1.2 µm, producing small grayish colonies that are typically less than 1.0 mm in diameter. It is facultatively anaerobic, Gram-positive, non-motile, non-sporogenous, and spherical. It often forms lenticular coccoid cells in pairs and chains, however, it can occasionally forms short rods with rounded ends in long chains, as its shape can differ depending on what media the species is grown on. L. mesenteroides grows best at 30°C, but can survive in temperatures ranging from 10°C to 30°C. Its optimum pH is 5.5, but can still show growth in pH of 4.5-7.0.

Food microbiology is the study of the microorganisms that inhibit, create, or contaminate food. This includes the study of microorganisms causing food spoilage; pathogens that may cause disease ; microbes used to produce fermented foods such as cheese, yogurt, bread, beer, and wine; and microbes with other useful roles, such as producing probiotics.

SCOBY is the commonly used acronym for "symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast", and is formed after the completion of a unique fermentation process of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), acetic acid bacteria (AAB), and yeast to form several sour foods and beverages such as kombucha and kimchi. Beer and wine also undergo fermentation with yeast, but the lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria components unique to SCOBY are usually viewed as a source of spoilage rather than a desired addition. Both LAB and AAB enter on the surface of barley and malt in beer fermentation and grapes in wine fermentation; LAB lower the pH of the beer while AAB take the ethanol produced from the yeast and oxidize it further into vinegar, resulting in a sour taste and smell. AAB are also responsible for the formation of the cellulose SCOBY.

Limosilactobacillus fermentum is a Gram-positive species in the heterofermentative genus Limosilactobacillus. It is associated with active dental caries lesions. It is also commonly found in fermenting animal and plant material including sourdough and cocoa fermentation. A few strains are considered probiotic or "friendly" bacteria in animals and at least one strain has been applied to treat urogenital infections in women. Some strains of lactobacilli formerly mistakenly classified as L. fermentum have since been reclassified as Limosilactobacillus reuteri. Commercialized strains of L. fermentum used as probiotics include PCC, ME-3 and CECT5716

A killer yeast is a yeast, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is able to secrete one of a number of toxic proteins which are lethal to susceptible cells. These "killer toxins" are polypeptides that kill sensitive cells of the same or related species, often functioning by creating pores in target cell membranes. These yeast cells are immune to the toxic effects of the protein due to an intrinsic immunity. Killer yeast strains can be a problem in commercial processing because they can kill desirable strains. The killer yeast system was first described in 1963. Study of killer toxins helped to better understand the secretion pathway of yeast, which is similar to those of more complex eukaryotes. It also can be used in treatment of some diseases, mainly those caused by fungi.

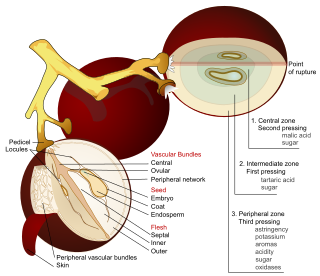

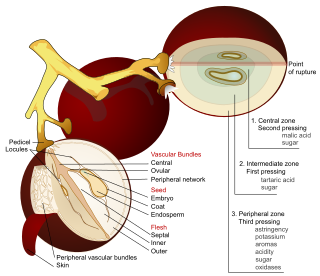

The acids in wine are an important component in both winemaking and the finished product of wine. They are present in both grapes and wine, having direct influences on the color, balance and taste of the wine as well as the growth and vitality of yeast during fermentation and protecting the wine from bacteria. The measure of the amount of acidity in wine is known as the “titratable acidity” or “total acidity”, which refers to the test that yields the total of all acids present, while strength of acidity is measured according to pH, with most wines having a pH between 2.9 and 3.9. Generally, the lower the pH, the higher the acidity in the wine. However, there is no direct connection between total acidity and pH. In wine tasting, the term “acidity” refers to the fresh, tart and sour attributes of the wine which are evaluated in relation to how well the acidity balances out the sweetness and bitter components of the wine such as tannins. Three primary acids are found in wine grapes: tartaric, malic, and citric acids. During the course of winemaking and in the finished wines, acetic, butyric, lactic, and succinic acids can play significant roles. Most of the acids involved with wine are fixed acids with the notable exception of acetic acid, mostly found in vinegar, which is volatile and can contribute to the wine fault known as volatile acidity. Sometimes, additional acids, such as ascorbic, sorbic and sulfurous acids, are used in winemaking.

Biopreservation is the use of natural or controlled microbiota or antimicrobials as a way of preserving food and extending its shelf life. The biopreservation of food, especially utilizing lactic acid bacteria (LAB) that are inhibitory to food spoilage microbes, has been practiced since early ages, at first unconsciously but eventually with an increasingly robust scientific foundation. Beneficial bacteria or the fermentation products produced by these bacteria are used in biopreservation to control spoilage and render pathogens inactive in food. There are a various modes of action through which microorganisms can interfere with the growth of others such as organic acid production, resulting in a reduction of pH and the antimicrobial activity of the un-dissociated acid molecules, a wide variety of small inhibitory molecules including hydrogen peroxide, etc. It is a benign ecological approach which is gaining increasing attention.

Food spoilage is the process where a food product becomes unsuitable to ingest by the consumer. The cause of such a process is due to many outside factors as a side-effect of the type of product it is, as well as how the product is packaged and stored. Due to food spoilage, one-third of the world's food produced for the consumption of humans is lost every year. Bacteria and various fungi are the cause of spoilage and can create serious consequences for the consumers, but there are preventive measures that can be taken.

The role of yeast in winemaking is the most important element that distinguishes wine from grape juice. In the absence of oxygen, yeast converts the sugars of wine grapes into alcohol and carbon dioxide through the process of fermentation. The more sugars in the grapes, the higher the potential alcohol level of the wine if the yeast are allowed to carry out fermentation to dryness. Sometimes winemakers will stop fermentation early in order to leave some residual sugars and sweetness in the wine such as with dessert wines. This can be achieved by dropping fermentation temperatures to the point where the yeast are inactive, sterile filtering the wine to remove the yeast or fortification with brandy or neutral spirits to kill off the yeast cells. If fermentation is unintentionally stopped, such as when the yeasts become exhausted of available nutrients and the wine has not yet reached dryness, this is considered a stuck fermentation.

Yeast assimilable nitrogen or YAN is the combination of free amino nitrogen (FAN), ammonia (NH3) and ammonium (NH4+) that is available for the wine yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae to use during fermentation. Outside of the fermentable sugars glucose and fructose, nitrogen is the most important nutrient needed to carry out a successful fermentation that doesn't end prior to the intended point of dryness or sees the development of off-odors and related wine faults. To this extent winemakers will often supplement the available YAN resources with nitrogen additives such as diammonium phosphate (DAP).

Rhodotorula glutinis is the type species of the genus Rhodotorula, a basidiomycetous genus of pink yeasts which contains 370 species. Heterogeneity of the genus has made its classification difficult with five varieties having been recognized; however, as of 2011, all are considered to represent a single taxon. The fungus is a common colonist of animals, foods and environmental materials. It can cause opportunistic infections, notably blood infection in the setting of significant underlying disease. It has been used industrially in the production of carotenoid pigments and as a biocontrol agent for post-harvest spoilage diseases of fruits.

Lachancea thermotolerans is a species of yeast.