Related Research Articles

The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the federal government and each state from denying or abridging a citizen's right to vote "on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." It was ratified on February 3, 1870, as the third and last of the Reconstruction Amendments.

Women's suffrage, or the right of women to vote, was established in the United States over the course of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, first in various states and localities, then nationally in 1920 with the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution.

James M. Hinds was the first U.S. Congressman assassinated in office. He served as member of the United States House of Representatives for Arkansas from June 24, 1868 until his assassination by the Ku Klux Klan. Hinds, who was white, was an advocate of civil rights for black former slaves during the Reconstruction era following the American Civil War.

The Industrial Exposition Building was located in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The building stood from 1886 to 1940 and was briefly the tallest structure in Minneapolis. In addition to smaller local exhibitions, it was the site of the 1892 Republican National Convention, the only major party convention to be held in Minnesota until the 2008 Republican National Convention.

William T. Francis was an American lawyer, politician, and diplomat from Minnesota. He was a successful personal and civil rights lawyer, winning discrimination cases against the police and employers, and successfully lobbying for state anti-discrimination and anti-lynching legislation. He was the U.S. Minister Resident/Consul General in Liberia, the first African-American diplomat from Minnesota. In Liberia, Francis conducted a nine-month inquiry into allegations of government involvement in slavery and forced labor. He died in post in Liberia of yellow fever. His report helped achieve a League of Nations investigation that ultimately forced the president, Charles D.B. King, and the vice president of Liberia, Allen Yancy, to resign in 1930.

The 2008 United States presidential election in Minnesota took place on November 4, 2008, and was part of the 2008 United States presidential election. Voters chose ten representatives, or electors to the Electoral College, who voted for president and vice president.

Anna Dickie Olesen was an American politician from the state of Minnesota who was the first woman to be nominated by a major party for the United States Senate.

Clara Hampson Ueland was an American community activist and suffragist. She was the first president of the Minnesota League of Women Voters and worked to advance public welfare legislation.

Julia Bullard Nelson (1842–1914) was an American temperance and women's rights activist from Red Wing, Minnesota. Following the death of her husband and their only child, she went south to Texas, in 1869, to teach former slaves in U.S. government-backed Freedmen's Bureau schools. Nelson spent the summers of the 1870s and 1880s in Minnesota, where she emerged as a state and national leader in the movement for women's suffrage and the temperance campaign against alcohol use.

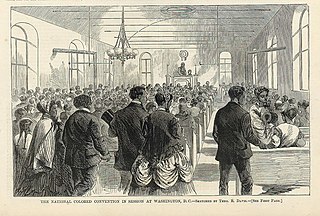

The Colored Conventions Movement, or Black Conventions Movement, was a series of national, regional, and state conventions held irregularly during the decades preceding and following the American Civil War. The delegates who attended these conventions consisted of both free and formerly enslaved African Americans, including religious leaders, businessmen, politicians, writers, publishers, editors, and abolitionists. The conventions provided "an organizational structure through which black men could maintain a distinct black leadership and pursue black abolitionist goals." Colored conventions occurred in thirty-one states across the United States and in Ontario, Canada. The movement involved more than five thousand delegates and tens of thousands of attendees.

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states, and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

Edwin R. Overall aka Edwin R. Williams was an abolitionist, civil rights activist, civil servant, and politician in Chicago and Omaha. In the 1850s and 1860s, he was involved in abolition and underground railroad activities headed at Chicago's Quinn Chapel AME Church. During the U. S. Civil War, he recruited blacks in Chicago to join the Union Army. After the war, he moved to Omaha, where he was involved in the founding of the National Afro-American League and a local branch of the same. He was the first black in Nebraska to be nominated to the state legislature in 1890. He lost the election, but in 1892, his friend Matthew O. Ricketts became the first African-American elected to the Nebraska legislature. He was also a leader in Omaha organized labor.

Cyrus Dicks Bell was a journalist, civil rights activist, and civic leader in Omaha, Nebraska. He owned and edited the black newspaper Afro-American Sentinel during the 1890s. He was an outspoken political independent and later in his life became a strong supporter of Democrats. He was a founding member of the state Afro-American League and frequently spoke out against lynchings and about other issues of civil rights.

John Lewis was a hotel keeper, musician, and civil rights activist in Omaha, Nebraska. He was proprietor of the Lewis House in the early days of Omaha. In 1879, he organized a brass band which was a fixture in African-American events in Omaha in the 1880s. He was active in the Nebraska State Convention of Colored Americans, a part of the Colored Conventions Movement and involved in Republican politics in Omaha.

W. H. C. Stephenson was a doctor, preacher, and civil rights activist in Virginia City, Nevada, and Omaha, Nebraska. He was probably the first black doctor in Nevada and worked for the rights of blacks in that city. He was noted for his efforts in support of black suffrage in Nevada at the passing of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870. He helped found the first Baptist church in Virginia City. He moved to Omaha in the late 1870s and continued his medical, religious, and civil rights work. He founded another Baptist church in Omaha, and was a prominent Republican and activist in the city.

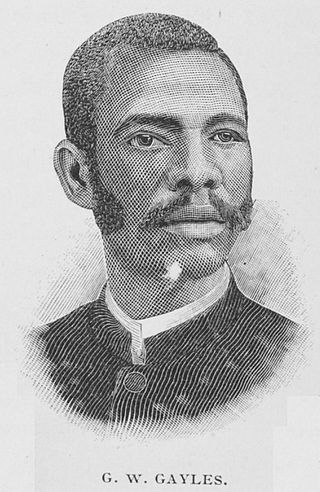

George Washington Gayles was an American Baptist minister and state legislator in Mississippi. He was in the Mississippi House of Representatives from 1872 until 1875 and to the Mississippi Senate from 1878 until 1886. He was a candidate for United States House of Representatives in 1892, but received only 6% of the vote due to the voter suppression laws of that period. He was also a noted Baptist minister and was known as the "Father of the Convention" of African American Baptists in Mississippi.

Nellie F. Griswold Francis was an African-American suffragist, civic leader, and civil rights activist. Francis founded and led the Everywoman Suffrage Club, an African-American suffragist group that helped win women the right to vote in Minnesota. She initiated, drafted, and lobbied for the adoption of a state anti-lynching bill that was signed into law in 1921. When she and her lawyer husband, William T. Francis, bought a home in a white neighborhood, they were the targets of a Ku Klux Klan terror campaign. In 1927, she moved to Monrovia, Liberia, with her husband when he was appointed U.S. envoy to Liberia. He died there from yellow fever in 1929. Francis is one of 25 women honored for their roles in achieving the women's right to vote in the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Memorial on the grounds of the State Capitol.

Mary "Mamie" Shields Pyle was a women's suffrage leader in the U.S. state of South Dakota. She was instrumental in the state's enactment of women's suffrage in 1918.

Women's rights issues in Ohio were put into the public eye in the early 1850s. Women inspired by the Declaration of Rights and Sentiments at the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention created newspapers and then set up their own conventions, including the 1850 Ohio Women's Rights Convention which was the first women's right's convention outside of New York and the first that was planned and run solely by women. These early efforts towards women's suffrage affected people in other states and helped energize the women's suffrage movement in Ohio. Women's rights groups formed throughout the state, with the Ohio Women's Rights Association (OWRA) founded in 1853. Other local women's suffrage groups are formed in the late 1860s. In 1894, women won the right to vote in school board elections in Ohio. The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was headquartered for a time in Warren, Ohio. Two efforts to vote on a constitutional amendment, one in 1912 and the other 1914 were unsuccessful, but drew national attention to women's suffrage. In 1916, women in East Cleveland gained the right to vote in municipal elections. A year later, women in Lakewood, Ohio and Columbus were given the right to vote in municipal elections. Also in 1917, the Reynolds Bill, which would allow women to vote in the next presidential election was passed, and then quickly repealed by a voter referendum sponsored by special-interest groups. On June 16, 1919, Ohio became the fifth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment.

The women's suffrage movement was active in Missouri mostly after the Civil War. There were significant developments in the St. Louis area, though groups and organized activity took place throughout the state. An early suffrage group, the Woman Suffrage Association of Missouri, was formed in 1867, attracting the attention of Susan B. Anthony and leading to news items around the state. This group, the first of its kind, lobbied the Missouri General Assembly for women's suffrage and established conventions. In the early 1870s, many women voted or registered to vote as an act of civil disobedience. The suffragist Virginia Minor was one of these women when she tried to register to vote on October 15, 1872. She and her husband, Francis Minor, sued, leading to a Supreme Court case that asserted the Fourteenth Amendment granted women the right to vote. The case, Minor v. Happersett, was decided against the Minors and led suffragists in the country to pursue legislative means to grant women suffrage.

References

- ↑ Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Minnesota (1869 : St. Paul, MN) (1869). "Proceedings of the Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Minnesota in Celebration of the Anniversary of Emancipation and the Reception of the Electoral Franchise: on the First of January, 1869". Courtesy of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Obscure St. Paul barber took a stand for racial equality". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

- ↑ "African American Suffrage in Minnesota, 1868 | MNopedia". www.mnopedia.org. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

- ↑ Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Minnesota (1869 : St. Paul, MN) (1869). "Proceedings of the Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Minnesota in Celebration of the Anniversary of Emancipation and the Reception of the Electoral Franchise: on the First of January, 1869". Courtesy of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library. Retrieved 2020-03-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Minnesota (1869 : St. Paul, MN) (1869). "Proceedings of the Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Minnesota in Celebration of the Anniversary of Emancipation and the Reception of the Electoral Franchise: on the First of January, 1869". Courtesy of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library. Retrieved 2020-03-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Minnesota (1869 : St. Paul, MN) (1869). "Proceedings of the Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Minnesota in Celebration of the Anniversary of Emancipation and the Reception of the Electoral Franchise: on the First of January, 1869". Courtesy of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library. Retrieved 2020-03-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Minnesota (1869 : St. Paul, MN) (1869). "Proceedings of the Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Minnesota in Celebration of the Anniversary of Emancipation and the Reception of the Electoral Franchise: on the First of January, 1869". Courtesy of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library. Retrieved 2020-03-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Minnesota (1869 : St. Paul, MN) (1869). "Proceedings of the Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Minnesota in Celebration of the Anniversary of Emancipation and the Reception of the Electoral Franchise: on the First of January, 1869". Courtesy of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ "African American Suffrage in Minnesota, 1868 | MNopedia". www.mnopedia.org. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

- ↑ "Obscure St. Paul barber took a stand for racial equality". Star Tribune. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

- ↑ Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Minnesota (1869 : St. Paul, MN) (1869). "Proceedings of the Convention of Colored Citizens of the State of Minnesota in Celebration of the Anniversary of Emancipation and the Reception of the Electoral Franchise: on the First of January, 1869". Courtesy of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)