Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that racial segregation laws did not violate the U.S. Constitution as long as the facilities for each race were equal in quality, a doctrine that came to be known as "separate but equal". The decision legitimized the many state laws re-establishing racial segregation that had been passed in the American South after the end of the Reconstruction Era (1865–1877).

Separate but equal was a legal doctrine in United States constitutional law, according to which racial segregation did not necessarily violate the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which nominally guaranteed "equal protection" under the law to all people. Under the doctrine, as long as the facilities provided to each "race" were equal, state and local governments could require that services, facilities, public accommodations, housing, medical care, education, employment, and transportation be segregated by "race", which was already the case throughout the states of the former Confederacy. The phrase was derived from a Louisiana law of 1890, although the law actually used the phrase "equal but separate".

A normal school is an institution created to train high school graduates to be teachers by educating them in the norms of pedagogy and curriculum. Most such schools are now called "teacher-training colleges" or "teachers' colleges", require a high school diploma, and may be part of a comprehensive university. Normal schools in the United States, Canada and Argentina trained teachers for primary schools, while in continental Europe, the equivalent colleges educated teachers for primary, secondary and tertiary schools.

Storer College was a historically black college in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, that operated from 1867 to 1955. A national icon for Black Americans, in the town where the end of American slavery began, as Frederick Douglass famously put it, it was a unique institution whose focus changed several times. There is no one category of college into which it fits neatly. Sometimes white students studied alongside Black students, which at the time was prohibited by law at state-supported schools in West Virginia and the other Southern states, and sometimes in the North.

The civil rights movement (1896–1954) was a long, primarily nonviolent action to bring full civil rights and equality under the law to all Americans. The era has had a lasting impact on American society – in its tactics, the increased social and legal acceptance of civil rights, and in its exposure of the prevalence and cost of racism.

The Lincoln Normal School, originally Lincoln School and later reorganized as State Normal School and University for the Education of Colored Teachers and Students, was a historic African American school expanded to include a normal school in Marion, Alabama. Founded less than two years after the end of the Civil War, it is one of the oldest HBCUs in the United States.

Lucy Craft Laney was an American educator who in 1883 founded the first school for black children in Augusta, Georgia. She was principal for 50 years of the Haines Institute for Industrial and Normal Education. In 1974 Laney was posthumously selected by Governor Jimmy Carter as one of the first three African Americans honored by having their portraits installed in the Georgia State Capitol. She also was inducted into the Georgia Women of Achievement.

Charles Henry Langston (1817–1892) was an American abolitionist and political activist who was active in Ohio and later in Kansas, during and after the American Civil War, where he worked for black suffrage and other civil rights. He was a spokesman for blacks of Kansas and "the West".

The civil rights movement (1865–1896) aimed to eliminate racial discrimination against African Americans, improve their educational and employment opportunities, and establish their electoral power, just after the abolition of slavery in the United States. The period from 1865 to 1895 saw a tremendous change in the fortunes of the black community following the elimination of slavery in the South.

Mary Virginia Cook Parrish was an early proponent of Black Baptist feminism, working to gain equality and social justice for all. After being given the opportunity to further her education, Cook-Parrish taught, wrote and spoke on many issues such as women's suffrage, equal rights in the areas of employment and education, social and political reform, and the importance of religion and a Christian education. She was at the founding session of the National Association of Colored Women in 1896 at the 19th Street Baptist Church in Washington D.C. and was a founder of the National Baptist Women's Convention in 1900.

James Milton Turner was a Reconstruction Era political leader, activist, educator, and diplomat. As consul general to Liberia, he was the first African-American to serve in the U.S. diplomatic corps.

The history of education in Missouri deals with schooling over two centuries, from the settlements In the early 19th century to the present. It covers students, teachers, schools, and educational policies.

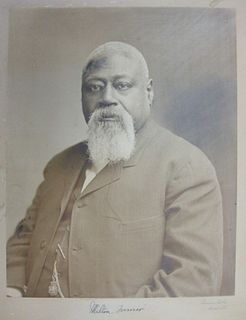

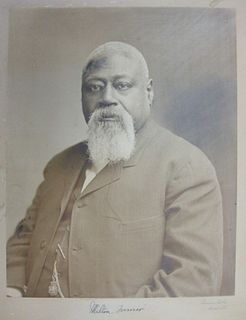

Philip H. Murray was an abolitionist, journalist, phrenologist, and civil rights activist who spent most of his career in St. Louis, Missouri. He grew up in Reading, Pennsylvania, where he participated in the abolitionist movement in that region. During the US Civil War he continued his work and served as a recruiting officer to help enlist blacks into the Union Army. After the war, he focused on journalism. In 1867, he established the first black newspaper in Kentucky, The Colored Kentuckian. He later moved to St. Louis where he continued to work in journalism and as an advocate for black education and civil rights. He was also the president of the first Negro Press Association.

African-American teachers educated African Americans and taught each other to read during slavery in the South. People who were enslaved ran small schools in secret, since teaching those enslaved to read was a crime. While, in the North, African Americans worked alongside with Whites. Many privileged African Americans in the North wanted their children taught with White children, and were pro-integration. The Black middle class preferred segregation. During the post-Reconstruction era African Americans built their own schools so they didn't have White control. The Black middle class believed that it could provide quality education for their community. This resulted in the foundation of teaching as a profession for Blacks. Some Black families had multiple individuals who dedicated their lives to teaching. They felt that they could empower their communities. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Southern States passed Jim Crow laws to mandate racial segregation in all aspects of society, and prevent Blacks from voting. Racism made it difficult for Black professionals to work in other professions. In 1950, African American teachers made up about half of African-American professionals.

Joseph Carter Corbin was a journalist and educator in the United States. Before the abolition of slavery, he was a journalist, teacher, and conductor on the Underground Railroad in Ohio and Kentucky. After the American Civil War, he moved to Arkansas where he served as superintendent of public schools from 1873 to 1874. He founded the predecessor of University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff and was its first principal from 1875 until 1902. He ended his career in education spending a decade as principal of Merrill High School in Pine Bluff. He also taught in Missouri.

Anna Evans Murray (1857–1955) was an American civic leader, educator, and early advocate of free kindergarten and the training of kindergarten teachers. In 1898 she successfully lobbied Congress for the first federal funds for kindergarten classes, and introduced kindergarten to the Washington, D.C. public school system.

Adella Hunt Logan was an African-American writer, educator, administrator and suffragist. Born during the Civil War, she earned her teaching credentials at Atlanta University, an historically black college founded by the American Missionary Association. She became a teacher at the Tuskegee Institute and became an activist for education and suffrage for women of color. As part of her advocacy, she published articles in some of the most noted black periodicals of her time.

The Kirkwood R-7 School District is a public school district headquartered in Kirkwood, Missouri.

Richard Baxter Foster was an American abolitionist, Union Army officer, and initial head of a college for African Americans in Jefferson City, Missouri. During the American Civil War, Foster volunteered to be an officer for the 1st Missouri Regiment of Colored Infantry regiment of the U.S. Army, largely recruited in Missouri, and helped set up educational program for its soldiers. In 1866 Foster headed the new college in Jefferson City, the Lincoln Institute, with financial support from his former regiment. The college is now named Lincoln University.

Sara Griffith Stanley Woodward was an African-American abolitionist, missionary teacher, and published author. Sara, sometimes listed as "Sarah", came from a biracial family, of which both black and white sides owned slaves. Despite this fact, she spent most of her working life to further the cause of freedom and civil rights for African Americans. Her family's wealth and affluence enabled her to obtain a diploma in "Ladies Courses" from Oberlin College, one of the first colleges in the United States to admit African Americans beginning in 1837. She wrote and published several abolitionist works in journal magazines, but her most famous writing was an address on behalf of the Delaware Ladies' Antislavery Society given at the State Convention of Colored Men during the 1856 election year. After the Civil War, she spent several years working as a teacher for the American Missionary Association, working in the North and in the South educating African-American children.