Related Research Articles

Kashrut is a set of dietary laws dealing with the foods that Jews are permitted to eat and how those foods must be prepared according to Jewish law. Food that may be consumed is deemed kosher, from the Ashkenazi pronunciation of the Hebrew term kashér, meaning "fit".

A mashgiach is a Jew who supervises the kashrut status of a kosher establishment. A mashgiach may supervise any type of food service establishment, including slaughterhouses, food manufacturers, hotels, caterers, nursing homes, restaurants, butchers, groceries, or cooperatives. The mashgiach usually works as the on-site supervisor and inspector, representing a kosher certification agency or a local rabbi, who actually makes the policy decisions for what is or is not acceptably kosher. Sometimes the certifying rabbi acts as his own mashgiach; such is the case in many small communities.

In Judaism, shechita is slaughtering of certain mammals and birds for food according to kashrut.

Kosher foods are those that conform to the Jewish dietary regulations of kashrut, primarily derived from Leviticus 11 and Deuteronomy 14:1-21. Food that may be consumed according to halakha (law) is termed kosher in English, from the Ashkenazi pronunciation of the Hebrew term kashér, meaning "fit". Food that is not in accordance with law is called treif meaning "torn."

The Orthodox Union is one of the largest Orthodox Jewish organizations in the United States. Founded in 1898, the OU supports a network of synagogues, youth programs, Jewish and Religious Zionist advocacy programs, programs for the disabled, localized religious study programs, and international units with locations in Israel and formerly in Ukraine. The OU maintains a kosher certification service, whose circled-U hechsher symbol, Ⓤ, is found on the labels of many kosher commercial and consumer food products.

Clara Lemlich Shavelson was a leader of the Uprising of 20,000, the massive strike of shirtwaist workers in New York's garment industry in 1909, where she spoke in Yiddish and called for action. Later blacklisted from the industry for her labor union work, she became a member of the Communist Party USA and a consumer activist. In her last years as a nursing home resident she helped to organize the staff.

Hebrew National is a brand of kosher hot dogs and other sausages made by ConAgra Foods.

Hullin or Chullin is the third tractate of the Mishnah in the Order of Kodashim and deals with the laws of ritual slaughter of animals and birds for meat in ordinary or non-consecrated use, and with the Jewish dietary laws in general, such as the laws governing the prohibition of mixing of meat (fleishig) and dairy (milchig) products.

In Islamic law dhabīḥah Arabic: ذَبِيحَة dhabīḥahIPA: [ðæˈbiːħɐ], 'slaughtered animal' is the prescribed method of ritual slaughter of all lawful halal animals. This method of slaughtering lawful animals has several conditions to be fulfilled. "The name of Allah" or "In the name of Allah" (Bismillah) has to be called by the butcher upon slaughter of each halal animal separately, and it should consist of a swift, deep incision with a very sharp knife on the throat, cutting the wind pipe, jugular veins and carotid arteries of both sides but leaving the spinal cord intact.

The Islamic dietary laws (halal) and the Jewish dietary laws are both quite detailed, and contain both points of similarity and discord. Both are the dietary laws and described in distinct religious texts: an explanation of the Islamic code of law found in the Quran and Sunnah and the Jewish code of laws found in the Torah and explained in the Talmud.

The legal aspects of ritual slaughter include the regulation of slaughterhouses, butchers, and religious personnel involved with traditional shechita (Jewish) and dhabiha (Islamic). Regulations also may extend to butchery products sold in accordance with kashrut and halal religious law. Governments regulate ritual slaughter, primarily through legislation and administrative law. In addition, compliance with oversight of ritual slaughter is monitored by governmental agencies and, on occasion, contested in litigation.

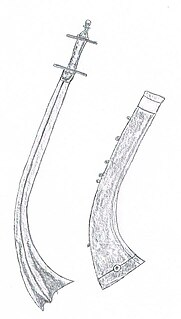

Jhatka, or Jhataka or chatka, is the meat from an animal killed instantaneously, such as by a single strike of a sword or axe to sever the head. This type of slaughter is preferred by Hindus and Sikhs. The animal must not be scared or shaken in any way before the slaughter.

Beth Hamedrash Hagodol is an Orthodox Jewish congregation that for over 120 years was located in a historic building at 60–64 Norfolk Street between Grand and Broome Streets in the Lower East Side neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. It was the first Eastern European congregation founded in New York City and the oldest Russian Jewish Orthodox congregation in the United States.

Ritual slaughter is the practice of slaughtering livestock for meat in the context of a ritual. Ritual slaughter involves a prescribed practice of slaughtering an animal for food production purposes. This differs from animal sacrifices that involve slaughtering animals, often in the context of rituals, for purposes other than mere food production.

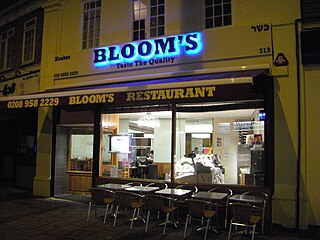

A kosher restaurant is an establishment that serves food that complies with Jewish dietary laws (kashrut). These businesses, which also include diners, cafés, pizzerias, fast food, and cafeterias, and are frequently in listings together with kosher bakeries, butchers, caterers, and other similar places, differ from kosher-style businesses in that they operate under rabbinical supervision, which requires that the laws of kashrut, as well as certain other Jewish laws, must be observed.

Tza'ar ba'alei chayim, literally "suffering of living creatures", is a Jewish commandment which bans causing animals unnecessary suffering. This concept is not clearly enunciated in the written Torah, but was accepted by the Talmud as being a biblical mandate. It is linked in the Talmud from the biblical law requiring people to assist in unloading burdens from animals.

Jewish vegetarianism is a commitment to vegetarianism that is connected to Judaism, Jewish ethics or Jewish identity. Jewish vegetarians often cite Jewish principles regarding animal welfare, environmental ethics, moral character, and health as reasons for adopting a vegetarian or vegan diet.

The "Kosher tax" is the idea that food companies and unwitting consumers are forced to pay money to support Judaism or Zionist causes and Israel through the costs of kosher certification. This claim is generally considered a conspiracy theory, antisemitic canard, or urban legend.

The 1973 Meat Boycott was a week-long national boycott in the United States to protest the rapidly increasing meat prices. It took place from 1 to 8 April 1973.

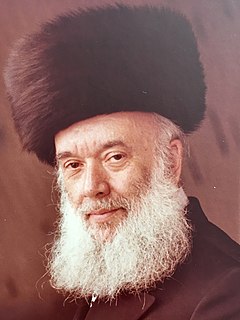

Rabbi Shlomo Zev Zweigenhaft was Rosh Hashochtim of Poland prior to the Holocaust. After the Holocaust, he was Chief Rabbi of Hannover and Lower Saxony. After emigrating to the United States he was a Rav Hamachshir and world-renowned for his expertise in all matters related to shechita and was described as the "foremost authority on shechita".

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "The Kosher Meat Boycott of 1902". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ↑ "Digital History". www.digitalhistory.uh.edu. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ↑ "Theodore Roosevelt - U.S. Presidents - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ↑ "Ask the Expert: Expensive Kosher Meat | My Jewish Learning". My Jewish Learning. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ↑ Leviticus 11:3 & Deuteronomy 14:6

- ↑ "Laws of Religion, Judaism and Islam". www.religiousrules.com. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ↑ "Leviticus 19:26".

- 1 2 3 Green, David B. (2016-05-15). "This Day in Jewish History 1902: Women Start Kosher Meat Boycott That Vanquishes a Monopoly". Haaretz. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ↑ Lerner, Breno (2012-01-01). The Barnacle Goose: And Other Kitchen Stories. Editora Melhoramentos. ISBN 978-8506004289.

- 1 2 3 ""Women resume riots against meat shops" – The 1902 Great Meat Boycott | LES History Month" . Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- 1 2 3 4 Hyman, Paula E. (1980-01-01). "Immigrant Women and Consumer Protest: The New York City Kosher Meat Boycott of 1902". American Jewish History. 70 (1): 91–105. JSTOR 23881992.

- ↑ "Kosher Meat Boycott of 1902 | My Jewish Learning". My Jewish Learning. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ↑ "Jewish women protest kosher meat prices on Lower East Side | Jewish Women's Archive". jwa.org. Retrieved 2017-04-28.

- ↑ "New York women boycotted kosher butchers". The Jewish Voice. Retrieved 2017-04-28.