Ellen Gould White was an American author and co-founder of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Along with other Adventist leaders such as Joseph Bates and her husband James White, she was instrumental within a small group of early Adventists who formed what became known as the Seventh-day Adventist Church. White is considered a leading figure in American vegetarian history. Smithsonian named her among the "100 Most Significant Americans of All Time".

Biblical inerrancy is the belief that the Bible "is without error or fault in all its teaching"; or, at least, that "Scripture in the original manuscripts does not affirm anything that is contrary to fact". Some equate inerrancy with biblical infallibility; others do not.

The Seventh-day Adventist Church had its roots in the Millerite movement of the 1830s to the 1840s, during the period of the Second Great Awakening, and was officially founded in 1863. Prominent figures in the early church included Hiram Edson, Ellen G. White, her husband James Springer White, Joseph Bates, and J. N. Andrews. Over the ensuing decades the church expanded from its original base in New England to become an international organization. Significant developments such the reviews initiated by evangelicals Donald Barnhouse and Walter Martin, in the 20th century led to its recognition as a Christian denomination.

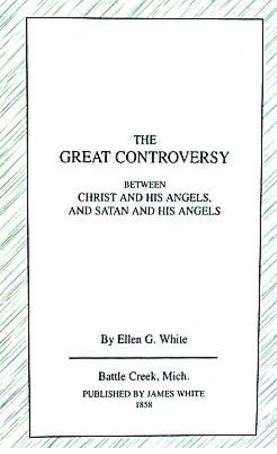

The Great Controversy is a book by Ellen G. White, one of the founders of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, and held in esteem as a prophetess or messenger of God among Seventh-day Adventist members. In it, White describes the "Great Controversy theme" between Jesus Christ and Satan, as played out over the millennia from its start in heaven, to its final end when the remnant who are faithful to God will be taken to heaven at the Second Advent of Christ, and the world is destroyed and recreated. Regarding the reason for writing the book, the author reported, "In this vision at Lovett's Grove, most of the matter of the Great Controversy which I had seen ten years before, was repeated, and I was shown that I must write it out."

The theology of the Seventh-day Adventist Church resembles that of Protestant Christianity, combining elements from Lutheran, Wesleyan-Arminian, and Anabaptist branches of Protestantism. Adventists believe in the infallibility of Scripture and teach that salvation comes from grace through faith in Jesus Christ. The 28 fundamental beliefs constitute the church's official doctrinal position.

Progressive Adventists are members of the Seventh-day Adventist Church who prefer different emphases or disagree with certain beliefs traditionally held by mainstream Adventism and officially by the church. While they are often described as liberal Adventism by other Adventists, the term "progressive" is generally preferred as a self-description. This article describes terms such as evangelical Adventism, cultural Adventism, charismatic Adventism, and progressive Adventism and others, which are generally related but have distinctions.

Most Seventh-day Adventists believe church co-founder Ellen G. White (1827–1915) was inspired by God as a prophet, today understood as a manifestation of the New Testament "gift of prophecy," as described in the official beliefs of the church. Her works are officially considered to hold a secondary role to the Bible, but in practice there is wide variation among Adventists as to exactly how much authority should be attributed to her writings. With understanding she claimed was received in visions, White made administrative decisions and gave personal messages of encouragement or rebuke to church members. Seventh-day Adventists believe that only the Bible is sufficient for forming doctrines and beliefs, a position Ellen White supported by statements inclusive of, "the Bible, and the Bible alone, is our rule of faith".

Alden Lloyd Thompson is a Seventh-day Adventist Christian theologian, author, and seminar presenter. He is also a professor of biblical studies at Walla Walla University in Washington, United States.

The 1888 Minneapolis General Conference Session was a meeting of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists held in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in October 1888. It is regarded as a landmark event in the history of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. Key participants were Alonzo T. Jones and Ellet J. Waggoner, who presented a message on justification supported by Ellen G. White, but resisted by leaders such as G. I. Butler, Uriah Smith and others. The session discussed crucial theological issues such as the meaning of "righteousness by faith", the nature of the Godhead, the relationship between law and grace, and Justification and its relationship to Sanctification.

Seventh-day Adventists Answer Questions on Doctrine is a book published by the Seventh-day Adventist Church in 1957 to help explain Adventism to conservative Protestants and Evangelicals. The book generated greater acceptance of the Adventist church within the evangelical community, where it had previously been widely regarded as a cult. However, it also proved to be one of the most controversial publications in Adventist history and the release of the book brought prolonged alienation and separation within Adventism and evangelicalism.

Historic Adventism is an informal designation for conservative individuals and organizations affiliated with the Seventh-day Adventist Church who seek to preserve certain traditional beliefs and practices of the church. They feel that the church leadership has shifted or departed from key doctrinal "pillars" ever since the middle of the 20th century. Specifically, they point to the publication in 1957 of a book entitled Seventh-day Adventists Answer Questions on Doctrine; which they feel undermines historic Adventist theology in favor of theology more compatible with evangelicalism. Historic Adventism has been erroneously applied by some to any Adventists that adhere to the teachings of the church as reflected in the church's fundamental beliefs such as the Sabbath or the Spirit of Prophecy. They misapply those who hold to mainstream traditional Adventist beliefs as synonymous with Historic Adventist.

George Raymond Knight is a leading Seventh-day Adventist historian, author, and educator. He is emeritus professor of church history at Andrews University. As of 2014 he is considered to be the best-selling and influential voice for the past three decades within the denomination.

Benjamin George Wilkinson (1872–1968) was a Seventh-day Adventist missionary, educator, and theologian. He served also as Dean of Theology at the Seventh-day Adventist Washington Missionary College which is located in Takoma Park, Maryland, near Washington, D.C. Wilkinson is considered one of the originators of the King James Only beliefs.

Ellet Joseph "E.J." Waggoner was a Seventh-day Adventist particularly known for his impact on the theology of the church, along with friend and associate Alonzo T. Jones at the 1888 Minneapolis General Conference Session. At the meeting of the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists Ellet J. Waggoner along with Alonzo T. Jones presented a message on justification supported by Ellen G. White, but resisted by church leaders such as G. I. Butler and others. He supported theological issues such as the meaning of "righteousness by faith", the nature of the Godhead, the relationship between law and grace, and Justification and its relationship to Sanctification.

Thought Inspiration is a form of divine inspiration in which revelation takes place in the mind of the writer, as opposed to verbal inspiration, in which the word of God is communicated directly to the writer. The theologian George La Piana claims that after 19th century advancements in philological and historical criticism showed sacred books of different religions to be similar in form and content, the "theological doctrine of biblical inspiration which had put these books in a class by themselves underwent a rapid change, from 'verbal inspiration' to 'thought inspiration' and from 'thought inspiration' to a vague 'moral inspiration,' such as could be attributed to many a book of ancient philosophy or poetry."

William Warren Prescott (1855–1944) was an administrator, educator, and scholar in the early Seventh-day Adventist Church.

Edward E. Heppenstall was a leading Bible scholar and theologian of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. A 1985 questionnaire of North American Adventist lecturers revealed Heppenstall was the Adventist writer who had most influenced them.

Seventh-day Adventists believe that Ellen G. White, one of the church's co-founders, was a prophetess, understood today as an expression of the New Testament spiritual gift of prophecy.

The Seventh-day Adventist Church pioneers were members of Seventh-day Adventist Church, part of the group of Millerites, who came together after the Great Disappointment across the United States and formed the Seventh-day Adventist Church. In 1860, the pioneers of the fledgling movement settled on the name, Seventh-day Adventist, representative of the church's distinguishing beliefs. Three years later, on May 21, 1863, the General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists was formed and the movement became an official organization.

The Pillars of Adventism are landmark doctrines for Seventh-day Adventists. They are Bible doctrines that define who they are as a people of faith; doctrines that are "non-negotiables" in Adventist theology. The Seventh-day Adventist church teaches that these Pillars are needed to prepare the world for the second coming of Jesus Christ, and sees them as a central part of its own mission. Adventists teach that the Seventh-day Adventist Church doctrines were both a continuation of the reformation started in the 16th century and a movement of the end time rising from the Millerites, bringing God's final messages and warnings to the world.