Related Research Articles

The Attica Prison Rebellion, also known as the Attica Prison Massacre, Attica Uprising or Attica Prison Riot, was the bloodiest prison riot in United States history, and is one of the best-known and most significant flashpoints of the prisoners' rights movement.

Goleniów is a town in Pomerania, northwestern Poland with 22,399 inhabitants (2004). It is the capital of Goleniów County in West Pomeranian Voivodeship ; previously it was in Szczecin Voivodeship (1975–1998). Town area is 12.5 square kilometres (4.8 sq mi), geographical situation 53°33'N and 14°49'E. It is situated in the centre of Goleniowska Forest on Goleniów Plain, near main roads numbers 3 and 6.

Nowogard is a town in northwestern Poland, in the West Pomeranian Voivodeship. As of 2004 it had a population of 16,733.

The ZOMO, known in English as Motorized Reserves of the Citizens' Militia, were paramilitary-police formations during the communist era in Poland. These elite units of Citizens' Militia (MO) were originally created to fight dangerous criminals, to provide security during mass events, and help in the case of natural disasters and other crises; however, they became known instead for their brutal and sometimes repressive lethal actions of riot control and their role in quelling civil rights protests.

The Iowa State Penitentiary (ISP) is an Iowa Department of Corrections maximum security prison for men located in the Lee County, Iowa community of Fort Madison. ISP is part of a larger correctional complex. The ISP itself is a 550-person maximum security unit. Also on the complex is a John Bennett Correctional Center - a 169-person medium security unit. Two minimum security farms with about 170 people are located within a few miles of the main complex. The complex also has a ten-person multiple care unit, and a 120-bed special needs unit for prisoners with mental illness or other diseases that require special medical care. In total there are currently about 950 inmates and 510 staff members.

Auburn Correctional Facility is a state prison on State Street in Auburn, New York, United States. It was built on land that was once a Cayuga village. It is classified as a maximum security facility.

William C. Holman Correctional Facility is an Alabama Department of Corrections prison located in unincorporated southwestern Escambia County, Alabama. The facility is along Alabama State Highway 21, 9 miles (14 km) north of Atmore in southern Alabama.

The Southern Ohio Correctional Facility is a maximum security prison located just outside Lucasville in Scioto County, Ohio. The prison was constructed in 1972. As of 2019, the warden is Ronald Erdos.

The Oklahoma State Penitentiary, nicknamed "Big Mac", is a prison of the Oklahoma Department of Corrections located in McAlester, Oklahoma, on 1,556 acres (6.30 km2). Opened in 1908 with 50 inmates in makeshift facilities, today the prison holds more than 750 male offenders, the vast majority of which are maximum-security inmates.

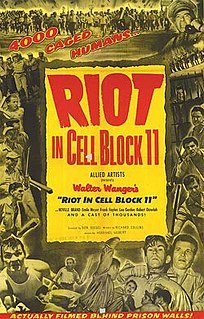

Riot in Cell Block 11 is a 1954 film noir crime film directed by Don Siegel and starring Neville Brand, Emile Meyer, Frank Faylen, Leo Gordon and Robert Osterloh. Quentin Tarantino called it "the best prison film ever made."

Leopoldov Prison is a 17th-century fortress built against Ottoman Turks that was converted into a high-security prison in the 19th century in the town of Leopoldov, Slovakia. Once the largest prison in the Kingdom of Hungary, in the 20th century it became known for housing political prisoners under the communist regime, notably the future communist President of Czechoslovakia Gustáv Husák.

Michigan State Prison or Jackson State Prison, which opened in 1839, was the first prison in Michigan. After 150 years, the prison was divided, starting in 1988, into four distinct prisons, still in Jackson: the Parnall Correctional Facility which is a minimum-security prison; the G. Robert Cotton Correctional Facility where prisoners can finish their general education; the Charles Egeler Reception and Guidance Center which is the common point of processing for all male state prisoners sentenced to any Michigan prison; and the Cooper Street Correctional Facility which is the common point for processing of all male state prisoners about to discharge, parole, or enter a community center or the camp program.

The Pacification of Wujek was a strike-breaking action by the Polish police and army at the Wujek Coal Mine in Katowice, Poland, culminating in the massacre of nine striking miners on December 16, 1981.

The Montana State Prison is a men's correctional facility of the Montana Department of Corrections in unincorporated Powell County, Montana, about 3.5 miles (5.6 km) west of Deer Lodge. The current facility was constructed between 1974 and 1979 in response to the continued degeneration of the original facility located in downtown Deer Lodge.

The Missouri State Penitentiary was a prison in Jefferson City, Missouri, that operated from 1836 to 2004. Part of the Missouri Department of Corrections, it served as the state of Missouri's primary maximum security institution. Before it closed, it was the oldest operating penal facility west of the Mississippi River. It was replaced by the Jefferson City Correctional Center, which opened on September 15, 2004.

The Kaohsiung Prison riot was a hostage situation that occurred at Kaohsiung Prison in Taiwan starting 11 February 2015. Six inmates, whose ringleader was a member of Bamboo Union, seized weapons, including assault rifles, and took the warden hostage for a 14-hour high-profile stand-off, which caught media attention nationwide. The group of inmates eventually committed mass suicide. The inmates protested that the former President of the Republic of China Chen Shui-bian, who jailed for 20 years for money laundering, was granted medical parole due to his status as a political prisoner while other prisoners were denied. This is the first ever prison riot with officials held hostage in the history of Taiwan.

The Kondengui and Buea prison riots occurred on July 22 and 24, 2019, respectively. While the first riot started off as a protest against poor prison conditions and unjust detainment, the second riot was carried out in support of the former. Both riots were violently quelled by security forces, and hundreds of prisoners were transported to undisclosed locations. The fate of these prisoners and rumors of casualties during the crushing of the riots had political implications in the ongoing Anglophone Crisis, and brought international attention to the prison conditions. Following the riots, many suspected participants were subjected to torture, and were brought to court and sentenced without their lawyers present.

The welcome parade or health trail or corredor polonês is a form of running the gauntlet used against new prisoners in some countries, including Poland in the twentieth century during the Polish People's Republic, and Egypt and Belarus in the twenty-first century.

The Guanare prison riot, also known as the Guanaremassacre, occurred in the Los Llanos prison in Guanare, Portuguesa state, Venezuela, on 1 May 2020. The events caused around 47 deaths, and 75 people were injured.

Political prisoners in Poland and Polish territories have existed throughout much of the 19th and 20th centuries. In the 19th century, some Polish political prisoners started using their situation of imprisonment to act politically. This phenomenon became visible as early as in the aftermath of the Greater Poland Uprising of 1848.

References

- ↑ The New York Times, At Least 3 Inmates are Dead in Riots at 4 Polish Prisons

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Adam Zadworny, Mozecie mnie juz puscic, Gazeta Wyborcza, 2009-12-11

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 "Wybuch buntu w polskich więzieniach". Archived from the original on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2011-07-10.

- 1 2 3 4 "Czas Warszawski, Lecą żurawie: Młoty w dłoń, kujmy broń, by Max Bronowicz". Archived from the original on 2011-10-03. Retrieved 2011-07-10.

- ↑ "Town of Czarne, tourist information". Archived from the original on 2012-03-26. Retrieved 2011-07-10.