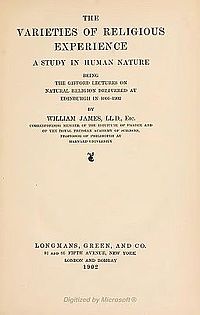

Summary

Dewey's overarching theme in A Common Faith is the role of distinct religious experience (separate from religions themselves, as outlined in the first chapter) in realizing human potential through action and imagination. Dewey lays out the direct purpose of this work in his closing statement at the end of the third chapter: "Here are all the elements for a religious faith that shall not be confined to sect, class, or race. Such a faith has always been implicitly the common faith of mankind. It remains to make it explicit and militant" (p. 80). [1] Much like in many of Dewey's other works, democracy is a common theme throughout his statements in A Common Faith.

There are three major themes present in A Common Faith. The first establishes distinct differences between "the religious" and religions themselves as experience. The second affirms God as "creative intersection of the ideal or possible and the real or actual," while the third establishes "the infusion of the religious as a pervasive mode of experience into democratic life" (Alexander, p. 23). [2]

In his review of A Common Faith, A. E. Elder states that "There is potential in man a religious attitude towards life - a natural capacity for faith - which can so enrich life and advance human well-being, that if through misunderstanding or other causes it is suppressed, then human life as a whole is adversely affected and remains a poor and stunted thing" (p. 235). [3] However, this religious attitude is not necessarily expressed through devotion to one particular religion; Dewey argues that this faith is present in experience itself. R.S. states in his review of A Common Faith that "…the central argument, as those who are acquainted with Professor Dewey's philosophy might expect, is designed to show that religion should be detached from its supernatural associations within organized historical institutions, and widened, on the basis of its function in experience, so as to cover all devotion to ideal ends inclusive enough to integrate a whole self and arouse emotional support" (p. 584). [4]

In reference to the idea of the religious in A Common Faith, Baurain states that for Dewey, "…the religious is characterized by a rejection of creeds, doctrines, rituals, and other elements of organized religion. Instead, an authentically religious attitude or orientation is existential and humanist. Moral faith rests not upon a divine Supreme Being or divinely revealed truths, but upon the dynamic potential of inquiry to discover knowledge and pursue ideals, that is, to act on experiential knowledge in order to improve life". [5] Central to this work is the idea that religious experience itself is not explicitly tied to singular religions, and that experience can and should be creatively harnessed to enrich life.

According to Ralston, Dewey unified the ideal and the real under the banner of religious experience in A Common Faith so as to avoid the metaphysical dualisms implicit in most doctrinal religion: "Dewey’s union of the ideal and the real under the heading of religious likewise reflects an attempt to 'convert the ontological . . . into the logical' by showing that religious is a quality of lived experience, not of a supernatural thing, church, object of reverence, divine idol or realm of supersensible objects. To do otherwise endangers the process of inquiry by bifurcating reality into pregiven realms of religious and nonreligious objects; the former transcending the experiential conditions of the latter." [6]

However, Dewey carefully defines the difference between ‘religion’ and ‘the religious’ in the first chapter of A Common Faith. M. C. Otto traces this difference, stating of A Common Faith that "Perhaps the most arresting thing is the distinction insisted upon between religion, any religion past or present, and the religious attitude or function. This is so sharply drawn that it almost seems as if Mr. Dewey were saying that every activity in the world may take on a religious character, excepting religion" (p. 496). [7]

Alexander posits that "...one of the central points Dewey seeks to make in A Common Faith is that both "faith" and the religious attitude have nothing to do with "doctrines" of any sort... Dewey states explicitly that his lectures were addressed to the antireligious naturalists and humanists who, he feared, had set up a new dualism, that between "Man vs. Nature," in place of the old" (p. 356). [8] In this way, this common faith is a push against the strict, binding doctrines of religious creed or scientific law that suppressed creativity and lived experience, disenfranchising many. In fact, in direct reference to A Common Faith, Dewey himself states that "…my book was written for the people who feel inarticulately that they have the essence of the religious with them and yet are repelled by the religions" (quoted in Webster p. 622). [9]

Dewey utilizes the word ‘common’ in the title of this body of work, referring to the potential for religious expression and spirituality in everyone and echoing his views on democracy. Alexander states, "To see something as "common," for Dewey, is to grasp it imaginatively in terms of its possibilities for growth. Dewey's use of the word "common" should not be taken to indicate a complacent optimism based on satisfaction with things as they are now. To grasp the possibilities in the present requires creative exploration and struggle" (p. 23). [10] Much in line with Dewey's other philosophies, Alexander goes on to say that "…a "common faith" means a faith in the potentialities of human life to become genuinely fulfilled in meaning and value, but only if those potentialities are actualized through action" (p. 21). [11]

Ultimately, in order to achieve this ‘common faith,’ Alexander states, "Dewey urges that we put the question of revealed truth aside and look at the effect such experiences have on the lives of the individuals who undergo them" (p. 24). [12]