She Stoops to Conquer is a comedy by Oliver Goldsmith, first performed in London in 1773. The play is a favourite for study by English literature and theatre classes in the English-speaking world. It is one of the few plays from the 18th century to have retained its appeal and is still regularly performed. The play has been adapted into a film several times, including in 1914 and 1923. Initially the play was titled Mistakes of a Night and the events within the play take place in one long night. In 1778, John O'Keeffe wrote a loose sequel, Tony Lumpkin in Town.

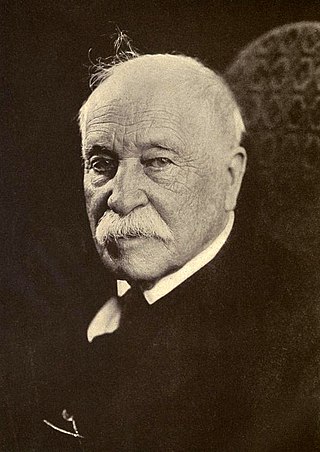

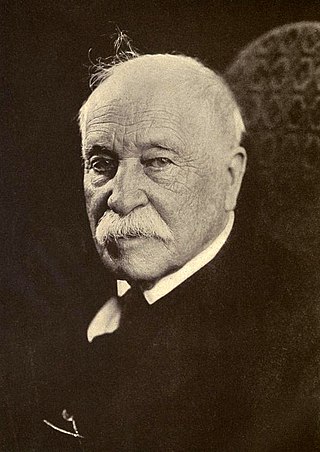

William Dean Howells was an American realist novelist, literary critic, and playwright, nicknamed "The Dean of American Letters". He was particularly known for his tenure as editor of The Atlantic Monthly, as well as for the novels The Rise of Silas Lapham and A Traveler from Altruria, and the Christmas story "Christmas Every Day," which was adapted into a 1996 film of the same name.

Varina Anne Banks Davis was the only First Lady of the Confederate States of America, and the longtime second wife of President Jefferson Davis. She moved to the presidential mansion in Richmond, Virginia, in mid-1861, and lived there for the remainder of the Civil War. Born and raised in the South and educated in Philadelphia, she had family on both sides of the conflict and unconventional views for a woman in her public role. She did not support the Confederacy's position on slavery, and was ambivalent about the war.

Frances Sargent Osgood was an American poet and one of the most popular women writers during her time. Nicknamed "Fanny", she was also famous for her exchange of romantic poems with Edgar Allan Poe.

How to Make an American Quilt is a 1995 American drama film based on the 1991 novel of the same name by Whitney Otto. Directed by Jocelyn Moorhouse, the film features Winona Ryder, Anne Bancroft, Ellen Burstyn, Kate Nelligan and Alfre Woodard. It is notable as being Jared Leto's film debut. Amblin Entertainment optioned Otto's novel in 1991, and were able to persuade Steven Spielberg to finance the screenplay's development. How to Make an American Quilt received mixed reviews from critics. It was a box-office success, grossing $41 million against a $10 million budget. The film was nominated for the Screen Actors Guild Award for Outstanding Performance by a Cast in a Motion Picture.

Virginia Eliza Poe was the wife of American writer Edgar Allan Poe. The couple were first cousins and publicly married when Virginia Clemm was 13 and Poe was 27. Biographers disagree as to the nature of the couple's relationship. Though their marriage was loving, some biographers suggest they viewed one another more like a brother and sister. In January 1842, she contracted tuberculosis, growing worse for five years until she died of the disease at the age of 24 in the family's cottage, at that time outside New York City.

Mary Katherine Horony Cummings, popularly known as Big Nose Kate, was a Hungarian-born American outlaw, gambler, prostitute and longtime companion and common-law wife of Old West gambler and gunfighter Doc Holliday. "Tough, stubborn and fearless", she was educated, but chose to work as a prostitute due to the independence it provided her. She is the only woman with whom Holliday is known to have had a relationship.

The Rise of Silas Lapham is a realist novel by William Dean Howells published in 1885. The story follows the materialistic rise of Silas Lapham from rags to riches, and his ensuing moral susceptibility. Silas earns a fortune in the paint business, but he lacks social standards, which he tries to attain through his daughter's marriage into the aristocratic Corey family. Silas' morality does not fail him. He loses his money but makes the right moral decision when his partner proposes the unethical selling of the mills to English settlers.

The Whole Family: a Novel by Twelve Authors (1908) is a collaborative novel told in twelve chapters, each by a different author. This unusual project was conceived by novelist William Dean Howells and carried out under the direction of Harper's Bazaar editor Elizabeth Jordan, who would write one of the chapters herself. Howells's idea for the novel was to show how an engagement or marriage would affect and be affected by an entire family. The project became somewhat curious for the way the authors' contentious interrelationships mirrored the sometimes dysfunctional family they described in their chapters. Howells had hoped Mark Twain would be one of the authors, but Twain did not participate. Other than Howells himself, Henry James was probably the best-known author to contribute. The novel was serialized in Harper's Bazaar in 1907–08 and published as a book by Harper's in late 1908.

A Modern Instance is a realistic novel written by William Dean Howells, and published in 1882 by J. R. Osgood & Co. The novel is about the deterioration of a once loving marriage under the influence of capitalistic greed. It is the first American novel by a canonical author to seriously consider divorce as a realistic outcome of marriage.

The Autumn Garden is a 1951 play by Lillian Hellman. The play is set in September, 1949 in a summer home in a resort on the Gulf of Mexico, about 100 miles from New Orleans. The play is a study of the defeats, disappointments and diminished expectations of people reaching middle age. For inspiration, Hellman drew on her memories of her time in her aunts' boardinghouse. Dashiell Hammett, who had been Hellman's lover for 20 years, helped her write the play and received 15 percent of the royalties. Of all Hellman's plays it was her favorite.

The Sleeping Car is a farce play in three parts by William Dean Howells, first published in the United States in 1883. This play takes place entirely within a 24-hour period on a railway sleeping car, and revolves around a woman's late night confusion regarding the premature appearance of her husband and brother. This work is one of Howells' minor works, but reflects the same tendencies towards literary realism as many of Howells' more famous works, including The Rise of Silas Lapham and A Modern Instance. This play is not well-read amongst modern readers, and is often overlooked in literary discussion due to its relative contemporary obscurity. Currently, this work is not being published by any publishing houses, but is available free through Project Gutenberg or other websites.

The Landlord at Lion's Head is a novel by American writer William Dean Howells. The book was first published in 1897 by Harper & Brothers.

The Lady of The Aroostook is a novel written by William Dean Howells in 1879. It was published in Cambridge, Massachusetts by H. O. Houghton and Company.

A Business Career is a novel by African-American author Charles Chesnutt that features the life of a "new woman" of the late 19th century; she enters the world of business instead of embracing the traditional roles of women. It explores a failed romance between two successful upper-class members. A family’s vendetta against the man who allegedly destroyed the family's fortune is revealed to be mistaken. The novel was unusual for its time as Chesnutt wrote only about white society.

Indian Summer is an 1886 novel by William Dean Howells. Though it was published after The Rise of Silas Lapham, it was written before The Rise of Silas Lapham. The setting for this novel was inspired by a trip Howells had recently taken with his family to Europe.

Dr. Breen's Practice is a novel, one of the earlier works by American author and literary critic William Dean Howells. Houghton Mifflin originally published the novel in 1881 in both Boston and New York. Howells wrote in the realist style, creating a faithful representation of the commonplace, and in this case describing everyday mannerisms that embody the daily lives of middle-class people.

An Imperative Duty is a short realist novel by William Dean Howells published in 1891. The novel explores the idea of "passing" through the racially mixed character of Rhoda Aldgate, a young woman whose aunt informs her that she is one-sixteenth African American. Rhoda lived her whole life "passing" as a white person.

Godolphin is a satirical 19th-century romance novel by British writer Edward Bulwer-Lytton. It is about the life of an idealistic man, Percy Godolphin, and his eventual lover, Constance Vernon. Written as a frame narrative, Godolphin provides a satirical insight into the day-to-day lives of the early 19th-century British elite. The story is told through the narration of two protagonists, Percy Godolphin and Constance Vernon, as they rise to prominence among the London elite.

How to Make an American Quilt (1991) is the debut novel of Whitney Otto. The novel tells the intersecting stories of several generations of women who together are part of the same quilting circle in the fictional town of Grasse, California. The novel was made into a movie of the same name in 1995 directed by Jocelyn Moorhouse and starring Winona Ryder as Finn Dodd.