Related Research Articles

The Country Wife is a Restoration comedy written by William Wycherley and first performed in 1675. A product of the tolerant early Restoration period, the play reflects an aristocratic and anti-Puritan ideology, and was controversial for its sexual explicitness even in its own time. The title contains a lewd pun with regard to the first syllable of "country". It is based on several plays by Molière, with added features that 1670s London audiences demanded: colloquial prose dialogue in place of Molière's verse, a complicated, fast-paced plot tangle, and many sex jokes. It turns on two indelicate plot devices: a rake's trick of pretending impotence to safely have clandestine affairs with married women, and the arrival in London of an inexperienced young "country wife", with her discovery of the joys of town life, especially the fascinating London men. The implied condition the Rake, Horner, claimed to suffer from was, he said, contracted in France whilst "dealing with common women". The only cure was to have a surgeon drastically reduce the extent of his manly stature; therefore, he could be no threat to any man's wife.

Richard Brome ; was an English dramatist of the Caroline era.

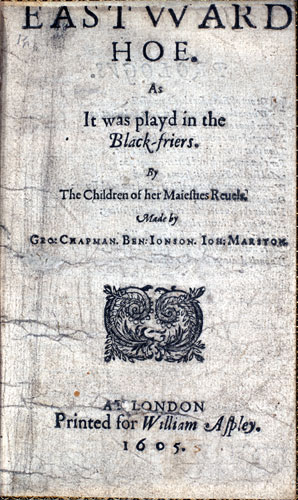

Eastward Hoe or Eastward Ho! is an early Jacobean-era stage play written by George Chapman, Ben Jonson and John Marston. The play was first performed at the Blackfriars Theatre by a company of boy actors known as the Children of the Queen's Revels in early August 1605, and it was printed in September the same year.

The Court Beggar is a Caroline era stage play written by Richard Brome. It was first performed by the acting company known as Beeston's Boys at the Cockpit Theatre. It has sometimes been identified as the seditious play, performed at the Cockpit in May 1640, which the Master of the Revels moved to have suppressed. However, the play's most recent editor, Marion O'Connor, dates it to "no earlier than the end of November 1640, and perhaps in the first months of 1641".

The Devil Is an Ass is a Jacobean comedy by Ben Jonson, first performed in 1616 and first published in 1631.

The Magnetic Lady, or Humours Reconciled is a Caroline-era stage play, the final comedy of Ben Jonson. It was licensed for performance by Sir Henry Herbert, the Master of the Revels, on 12 October 1632, and first published in 1641, in Volume II of the second folio collection of Jonson's works.

The English Moor, or the Mock Marriage is a Caroline era stage play, a comedy written by Richard Brome, noteworthy in its use of the stage device of blackface make-up. Registered in 1640, it was first printed in 1659, and, uniquely among the plays of Brome's canon, also survives in a manuscript version.

The Antipodes is a Caroline era stage play, a comedy written by Richard Brome c. 1636. Many critics have ranked The Antipodes as "his best play...Brome's masterpiece," and one of the best Caroline comedies – "gay, imaginative, and spirited...;" "the most sophisticated and ingenious of Brome's satires." Brome's play is "a funhouse mirror" in which the audience members could "view the nature of their society."

The Northern Lass is a Caroline era stage play, a comedy by Richard Brome that premiered onstage in 1629 and was first printed in 1632. A popular hit, and one of his earliest successes, the play provided a foundation for Brome's career as a dramatist.

The Mistaken Husband is a Restoration comedy in the canon of John Dryden's dramatic works, where it has constituted a long-standing authorship problem.

The New Academy, or the New Exchange is a Caroline era stage play, a comedy written by Richard Brome. It was first printed in 1659.

The Lovesick Court, or the Ambitious Politique is a Caroline-era stage play, a tragicomedy written by Richard Brome, and first published in 1659.

The City Wit, or the Woman Wears the Breeches is a Caroline era stage play, a comedy written by Richard Brome that is sometimes classed among his best works. It was first published when it was included in the Five New Plays of 1653, the collection of Brome works published by Humphrey Moseley, Richard Marriot, and Thomas Dring.

The Damoiselle, or the New Ordinary is a Caroline era stage play, a comedy by Richard Brome that was first published in the 1653 Brome collection Five New Plays, issued by Humphrey Moseley, Richard Marriot, and Thomas Dring.

The Queen's Exchange is a Caroline era stage play, a tragicomedy written by Richard Brome.

The Parson's Wedding is a Caroline era stage play, a comedy written by Thomas Killigrew. Often regarded as the author's best play, the drama has sometimes been considered an anticipation of Restoration comedy, written a generation before the Restoration; "its general tone foreshadows the comedy of the Restoration from which the play is in many respects indistinguishable."

A Fine Companion is a Caroline era stage play, a comedy written by Shackerley Marmion that was first printed in 1633. It is one of only three surviving plays by Marmion.

Mary Knep, also Knepp, Nepp, Knip, or Knipp, was an English actress and one of the first generation of female performers to appear on the public stage during the Restoration era.

Cupid's Whirligig, by Edward Sharpham (1576-1608), is a city comedy set in London about a husband that suspects his wife of having affairs with other men and is consumed with irrational jealousy. It was first published in quarto in 1607, entered in the Stationer's Register with the name "A Comedie called Cupids Whirlegigge." It was performed that year by the Children of the King's Revels in the Whitefriars Theatre where Ben Jonson's Epicene was also said to have been performed.

References

- ↑ James Orchard Halliwell-Phillipps, A Dictionary of Old English Plays, London, J. R. Smith, 1860; p. 159.

- ↑ Matthew Steggle, Richard Brome: Place and Politics on the Caroline Stage, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2004; p. 155.

- ↑ Clarence Edward Andrews, Richard Brome: A Study of His Life and Works, New York, Henry Holt, 1913; p. 107.

- ↑ Ira Clark, "The Widow Hunt on the Tudor-Stuart Stage," SEL: Studies in English Literature 1500–1900 Vol. 41 No. 2 (Spring 2001), pp. 399–416.

- ↑ Henry Benjamin Wheatley, London, Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions, London, Scribner & Welford, 1891; Vol. 2, pp. 82–3.

- ↑ Steggle, p. 141.

- ↑ Andrews, p. 77.

- ↑ Ira Clark, "The Marital Double Standard in Tudor and Stuart Lives and Writing: Some Problems," in: Medieval and Renaissance Drama in England, Vol. 9, edited by John Pitcher: Madison, NJ, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997; pp. 34–55.

- ↑ Mary Ann O'Donnell, Aphra Behn: An Annotated Bibliography of Primary and Secondary Sources, London, Ashgate, 2004; pp. 258–60.