Related Research Articles

The Bacchanali were unofficial, privately funded popular Roman festivals of Bacchus, based on various ecstatic elements of the Greek Dionysia. They were almost certainly associated with Rome's native cult of Liber, and probably arrived in Rome itself around 200 BC. Like all mystery religions of the ancient world, very little is known of their rites. They seem to have been popular and well-organised throughout the central and southern Italian peninsula.

In Greek mythology, Pittheus was the king of Troezen, city in Argolis, which he had named after his brother Troezen.

The Senate was the governing and advisory assembly of the aristocracy in the ancient Roman Republic. It was not an elected body, but one whose members were appointed by the consuls, and later by the censors, which were appointed by the aristocratic Centuriate Assembly. After a Roman magistrate served his term in office, it usually was followed with automatic appointment to the Senate. According to the Greek historian Polybius, the principal source on the Constitution of the Roman Republic, the Roman Senate was the predominant branch of government. Polybius noted that it was the consuls who led the armies and the civil government in Rome, and it was the Roman assemblies which had the ultimate authority over elections, legislation, and criminal trials. However, since the Senate controlled money, administration, and the details of foreign policy, it had the most control over day-to-day life. The power and authority of the Senate derived from precedent, the high caliber and prestige of the senators, and the Senate's unbroken lineage, which dated back to the founding of the Republic in 509 BC. It developed from the Senate of the Roman Kingdom, and became the Senate of the Roman Empire.

Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso was a Roman statesman during the reigns of Augustus and Tiberius. He served as consul in 7 BC, after which he was appointed governor of Hispania and consul of Africa. Piso is best known for being accused of poisoning and killing Germanicus, the heir of emperor Tiberius.

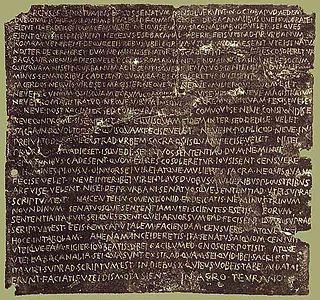

The senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus is an Old Latin inscription dating to 186 BC. It was discovered in 1640 at Tiriolo, in Calabria, southern Italy. Published by the presiding praetor, it conveys the substance of a decree of the Roman Senate prohibiting the Bacchanalia throughout all Italy, except in certain special cases which must be approved specifically by the Senate.

Aerarium, from aes + -ārium, was the name given in Ancient Rome to the public treasury, and in a secondary sense to the public finances.

The senatus consultum ultimum is the modern term given to resolutions of the Roman Senate lending its moral support for magistrates to use the full extent of their powers and ignore the laws to safeguard the state.

The Lex Papia et Poppaea, also referred to as the Lex Iulia et Papia, was a Roman law introduced in 9 AD to encourage and strengthen marriage. It included provisions against adultery and against celibacy after a certain age and complemented and supplemented Augustus' Lex Iulia de maritandis ordinibus of 18 BC and the Lex Iulia de adulteriis coercendis of 17 BC. The law was introduced by the suffect consuls of that year, Marcus Papius Mutilus and Quintus Poppaeus Secundus, although they themselves were unmarried.

Quintus Junius Arulenus Rusticus was a Roman Senator and a friend and follower of Thrasea Paetus, and like him an ardent admirer of Stoic philosophy. Arulenus Rusticus attained a suffect consulship in the nundinium of September to December 92 with Gaius Julius Silanus as his colleague. He was one of a group of Stoics who opposed the perceived tyranny and autocratic tendencies of certain emperors, known today as the Stoic Opposition.

The Roman Senate was the highest and constituting assembly of ancient Rome and its aristocracy. With different powers throughout its existence it lasted from the first days of the city of Rome as the Senate of the Roman Kingdom, to the Senate of the Roman Republic and Senate of the Roman Empire and eventually the Byzantine Senate of the Eastern Roman Empire, existing well into the post-classical era and Middle Ages.

The gens Carvilia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome, which first distinguished itself during the Samnite Wars. The first member of this gens to achieve the consulship was Spurius Carvilius Maximus, in 293 BC.

A senatus consultum is a text emanating from the senate in Ancient Rome. It is used in the modern phrase senatus consultum ultimum.

The gens Cosconia was a plebeian family at Rome. Members of this gens are first mentioned in the Second Punic War, but none ever obtained the honours of the consulship; the first who held a curule office was Marcus Cosconius, praetor in 135 BC.

The aes hordearium was an annual allotment of 2,000 asses paid during the Roman Republic to an equus publicus for his military horse's upkeep. This money was paid by single women, which included both maidens and widows (viduae), and orphans (orbi), provided they possessed a certain amount of property, on the principle, as Barthold Georg Niebuhr remarks, "that in a military state, the women and children ought to contribute for those who fight in behalf of them and the commonwealth; it being borne in mind, that they were not included in the census." The equites had a right to distrain if the aes hordearium was not paid.

The aes equestre was an allotment paid during the Roman Republic to each cavalryman to provide him with a horse. This was said to have been instituted by Servius Tullius as part of his reorganization of the military. This allotment was 10,000 asses, to be given to the Equus publicus out of the public treasury of Rome. A similar allotment, the aes hordearium paid for the horses' upkeep, and was funded by a tax of 2,000 ases annually on unmarried women and orphans possessing a certain amount of property

The gens Seria was a minor plebeian family at ancient Rome. Members of this gens rose to prominence during the second century, attaining the consulship twice, and holding various other offices under the Nerva-Antonine dynasty.

In ancient Rome, contubernium was a quasi-marital relationship between two slaves or between a slave (servus) and a free person who was usually a former slave or the child of a former slave. A slave involved in such a relationship was called contubernalis, the basic and general meaning of which was "companion".

The ancient Roman state encountered various kinds of external and internal emergencies. As such, they developed various responses to those issues.

Gnaeus Aufidius was a nobleman of ancient Rome, a member of the Aufidia gens, who lived in the 2nd century BC.