Related Research Articles

James McCune Smith was an American physician, apothecary, abolitionist and author who was born in Manhattan. He was the first African American to hold a medical degree, awarded by the University of Glasgow in Glasgow, Scotland. After his return to the United States, he became the first African American to run a pharmacy in the nation.

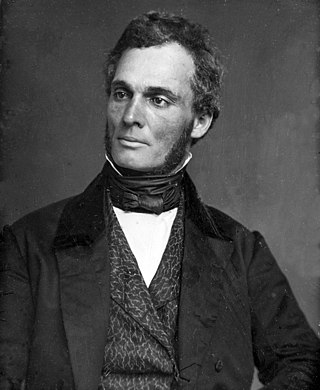

Robert Purvis was an American abolitionist in the United States. He was born in Charleston, South Carolina, and was likely educated at Amherst Academy, a secondary school in Amherst, Massachusetts. He spent most of his life in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In 1833 he helped found the American Anti-Slavery Society and the Library Company of Colored People. From 1845 to 1850 he served as president of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and also traveled to Britain to gain support for the movement.

Theodore Sedgwick Wright (1797–1847), sometimes Theodore Sedgewick Wright, was an African-American abolitionist and minister who was active in New York City, where he led the First Colored Presbyterian Church as its second pastor. He was the first African American to attend Princeton Theological Seminary, from which he graduated in 1828 or 1829. In 1833 he became a founding member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, an interracial group that included Samuel Cornish, a Black Presbyterian, and many Congregationalists, and served on its executive committee until 1840.

A dress code is a set of rules, often written, with regard to what clothing groups of people must wear. Dress codes are created out of social perceptions and norms, and vary based on purpose, circumstances, and occasions. Different societies and cultures are likely to have different dress codes, Western dress codes being a prominent example.

A Dorcas society is a local group of people, usually based in a church, with a mission of providing clothing to the poor. Dorcas societies are named after Dorcas, a person described in the Acts of the Apostles.

Freedom's Journal was the first African-American owned and operated newspaper published in the United States. Founded by Rev. John Wilk and other free Black men in New York City, it was published weekly starting with the 16 March 1827 issue. Freedom's Journal was superseded in 1829 by The Rights of All, published between 1829 and 1830 by Samuel Cornish, the former senior editor of the Journal. The View covered it as part of Black History Month in 2021.

Thomas L. Jennings was an American Moor inventor, tradesman, entrepreneur, and abolitionist in New York City, New York. He has the distinction of being the first American Moor patent-holder in history; he was granted the patent in 1821 for his novel method of dry cleaning. Jennings' invention, along with his business expertise, yielded a significant personal fortune much of which he put into the Abolitionist movement in the United States.

Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley was an American seamstress, activist, and writer who lived in Washington, D.C. She was best known as the personal dressmaker and confidante of Mary Todd Lincoln.

Thomas Dalton (1794–1883) was a free African American raised in Massachusetts who was dedicated to improving the lives of people of color. He was active with his wife Lucy Lew Dalton, Charlestown, Massachusetts, in the founding or ongoing activities of local educational organizations, including the Massachusetts General Colored Association, New England Anti-Slavery Society, Boston Mutual Lyceum, and Infant School Association, and campaigned for school integration, which was achieved in 1855.

Lucretia Mott was an American Quaker, abolitionist, women's rights activist, and social reformer. She had formed the idea of reforming the position of women in society when she was amongst the women excluded from the World Anti-Slavery Convention held in London in 1840. In 1848, she was invited by Jane Hunt to a meeting that led to the first public gathering about women's rights, the Seneca Falls Convention, during which Mott co-wrote the Declaration of Sentiments.

The American Equal Rights Association (AERA) was formed in 1866 in the United States. According to its constitution, its purpose was "to secure Equal Rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color or sex." Some of the more prominent reform activists of that time were members, including women and men, blacks and whites.

The Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS) was founded in December 1833 and dissolved in March 1870 following the ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. It was founded by eighteen women, including Mary Ann M'Clintock, Margaretta Forten, her mother Charlotte, and Forten's sisters Sarah and Harriet.

Sarah Mapps Douglass was an American educator, abolitionist, writer, and public lecturer. Her painted images on her written letters may be the first or earliest surviving examples of signed paintings by an African-American woman. These paintings are contained within the Cassey Dickerson Album, a rare collection of 19th-century friendship letters between a group of women.

John Telemachus Hilton was an African-American abolitionist, author, and businessman, who established barber, furniture dealer, and employment agency businesses. He was a Prince Hall Mason and established the Prince Hall National Grand Lodge of North America and served as its first National Grand Master for ten years. He also was a founding member of the Massachusetts General Colored Association, and active member and author in the Anti-Slavery movement.

Caroline Still Anderson was an American physician, educator, and activist. She was a pioneering physician in the Philadelphia African-American community and one of the first Black women to become a physician in the United States.

Henrietta Green Regulus Ray (1808–1836) was an African-American female activist living in New York City who advocated for women's education and independence. She helped found the African Dorcas Association, an organization that worked to provide clothing to students of the African Free School, and she became the organization's secretary in 1828. In 1834, she married Rev. Charles B. Ray, an African-American abolitionist and owner and editor of the Colored American, a weekly newspaper. Around the same time as her marriage, she also was elected as the first president of the New York Female Literary Society, which was "formed for the purpose of acquiring literary and scientific knowledge." She died in 1836 of tuberculosis.

Harriet Forten Purvis was an African-American abolitionist and first generation suffragist. With her mother and sisters, she formed the first biracial women's abolitionist group, the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. She hosted anti-slavery events at her home and with her husband Robert Purvis ran an Underground Railroad station. Robert and Harriet also founded the Gilbert Lyceum. She fought against segregation and for the right for blacks to vote after the Civil War.

Amy Hester "Hetty" Reckless was a runaway slave who became part of the American abolitionist movement. She campaigned against slavery and was part of the Underground Railroad, operating a Philadelphia safe house. She fought against prostitution and vice, working toward improving education and skills for the black community. Through efforts including operating a women's shelter, supporting Sunday Schools and attending conferences, she became a leader in the abolitionist community. After her former master's death, she returned to New Jersey and continued working to assist escaping slaves throughout the Civil War.

Grace Bustill Douglass was an African-American abolitionist and women's rights advocate. Her family was one of the first prominent free black families in the United States. Her family's history is one of the best documented for a black family during this period, dating from 1732 until 1925.

Hester Lane, was an American abolitionist, philanthropist, entrepreneur, and political activist. Born into slavery in Maryland, she settled down in New York as a free woman. Lane was known in New York for her approach to adding color pigment to walls using whitewash, freeing slaves in Maryland through purchasing them, and the controversy surrounding her failed nomination to the American Anti-Slavery Society. She died in July 1849 during the cholera epidemic.

References

- ↑ "Timeline: African Free School". MyHistory.Org. New-York Historical Society.

- 1 2 3 Fasick, Laura (2014-02-16). "African Dorcas Society—an early PTA?". Teacups and Tyrants-Viewing today through the light of the past. Retrieved 2016-10-06.

- ↑ Harris, Leslie M. (2004). In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226317755.

- 1 2 Alexander, Leslie M. (2008). African or American?: Black Identity and Political Activism in New York City, 1784-1861. University of Illinois Press.

- ↑ "Constitution (of the African Dorcas Association)". Freedom's Journal. 1828.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Yellin, Jean Fagan; Van Horne, John C. (1994). The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women's Political Culture in Antebellum America . Ithaca, New York: Library Company of Philadelphia. pp. 123–127. ISBN 0801480116.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Alexander, Leslie; Rucker, Walter C. (2010). Encyclopedia of African American History . Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 295–296. ISBN 9781851097692.

- ↑ Bacon, Jacqueline (2007). Freedom's Journal: The First African-American Newspaper. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. pp. 139–142. ISBN 9780739118931.