Keynesian economics are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand strongly influences economic output and inflation. In the Keynesian view, aggregate demand does not necessarily equal the productive capacity of the economy. Instead, it is influenced by a host of factors – sometimes behaving erratically – affecting production, employment, and inflation.

Microeconomics is a branch of mainstream economics that studies the behavior of individuals and firms in making decisions regarding the allocation of scarce resources and the interactions among these individuals and firms. Microeconomics focuses on the study of individual markets, sectors, or industries as opposed to the national economy as whole, which is studied in macroeconomics.

Macroeconomics is a branch of economics that deals with the performance, structure, behavior, and decision-making of an economy as a whole. For example, using interest rates, taxes, and government spending to regulate an economy's growth and stability. This includes regional, national, and global economies.

Neoclassical economics is an approach to economics in which the production, consumption, and valuation (pricing) of goods and services are observed as driven by the supply and demand model. According to this line of thought, the value of a good or service is determined through a hypothetical maximization of utility by income-constrained individuals and of profits by firms facing production costs and employing available information and factors of production. This approach has often been justified by appealing to rational choice theory, a theory that has come under considerable question in recent years.

In economics, general equilibrium theory attempts to explain the behavior of supply, demand, and prices in a whole economy with several or many interacting markets, by seeking to prove that the interaction of demand and supply will result in an overall general equilibrium. General equilibrium theory contrasts to the theory of partial equilibrium, which analyzes a specific part of an economy while its other factors are held constant. In general equilibrium, constant influences are considered to be noneconomic, therefore, resulting beyond the natural scope of economic analysis. The noneconomic influences is possible to be non-constant when the economic variables change, and the prediction accuracy may depend on the independence of the economic factors.

This aims to be a complete article list of economics topics:

Sir John Richards Hicks was a British economist. He is considered one of the most important and influential economists of the twentieth century. The most familiar of his many contributions in the field of economics were his statement of consumer demand theory in microeconomics, and the IS–LM model (1937), which summarised a Keynesian view of macroeconomics. His book Value and Capital (1939) significantly extended general-equilibrium and value theory. The compensated demand function is named the Hicksian demand function in memory of him.

In macroeconomics, aggregate demand (AD) or domestic final demand (DFD) is the total demand for final goods and services in an economy at a given time. It is often called effective demand, though at other times this term is distinguished. This is the demand for the gross domestic product of a country. It specifies the amount of goods and services that will be purchased at all possible price levels. Consumer spending, investment, corporate and government expenditure, and net exports make up the aggregate demand.

In classical economics, Say's law, or the law of markets, is the claim that the production of a product creates demand for another product by providing something of value which can be exchanged for that other product. So, production is the source of demand. In his principal work, A Treatise on Political Economy, Jean-Baptiste Say wrote: "A product is no sooner created, than it, from that instant, affords a market for other products to the full extent of its own value." And also, "As each of us can only purchase the productions of others with his own productions – as the value we can buy is equal to the value we can produce, the more men can produce, the more they will purchase."

In economics, effective demand (ED) in a market is the demand for a product or service which occurs when purchasers are constrained in a different market. It contrasts with notional demand, which is the demand that occurs when purchasers are not constrained in any other market. In the aggregated market for goods in general, demand, notional or effective, is referred to as aggregate demand. The concept of effective supply parallels the concept of effective demand. The concept of effective demand or supply becomes relevant when markets do not continuously maintain equilibrium prices.

Consumption is the act of using resources to satisfy current needs and wants. It is seen in contrast to investing, which is spending for acquisition of future income. Consumption is a major concept in economics and is also studied in many other social sciences.

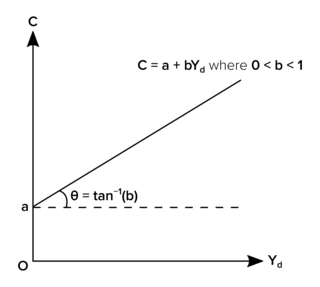

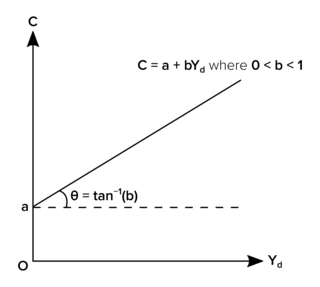

In economics, the consumption function describes a relationship between consumption and disposable income. The concept is believed to have been introduced into macroeconomics by John Maynard Keynes in 1936, who used it to develop the notion of a government spending multiplier.

In economics, an aggregate is a summary measure. It replaces a vector that is composed of many real numbers by a single real number, or a scalar. Consequently, there occur various problems that are inherent in the formulations that use aggregated variables.

Dynamic stochastic general equilibrium modeling is a macroeconomic method which is often employed by monetary and fiscal authorities for policy analysis, explaining historical time-series data, as well as future forecasting purposes. DSGE econometric modelling applies general equilibrium theory and microeconomic principles in a tractable manner to postulate economic phenomena, such as economic growth and business cycles, as well as policy effects and market shocks.

Microfoundations are an effort to understand macroeconomic phenomena in terms of economic agents' behaviors and their interactions. Research in microfoundations explores the link between macroeconomic and microeconomic principles in order to explore the aggregate relationships in macroeconomic models.

The neoclassical synthesis (NCS), neoclassical–Keynesian synthesis, or just neo-Keynesianism was a neoclassical economics academic movement and paradigm in economics that worked towards reconciling the macroeconomic thought of John Maynard Keynes in his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). It was formulated most notably by John Hicks (1937), Franco Modigliani (1944), and Paul Samuelson (1948), who dominated economics in the post-war period and formed the mainstream of macroeconomic thought in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s.

New classical macroeconomics, sometimes simply called new classical economics, is a school of thought in macroeconomics that builds its analysis entirely on a neoclassical framework. Specifically, it emphasizes the importance of rigorous foundations based on microeconomics, especially rational expectations.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to economics:

Macroeconomic theory has its origins in the study of business cycles and monetary theory. In general, early theorists believed monetary factors could not affect real factors such as real output. John Maynard Keynes attacked some of these "classical" theories and produced a general theory that described the whole economy in terms of aggregates rather than individual, microeconomic parts. Attempting to explain unemployment and recessions, he noticed the tendency for people and businesses to hoard cash and avoid investment during a recession. He argued that this invalidated the assumptions of classical economists who thought that markets always clear, leaving no surplus of goods and no willing labor left idle.

The Principle of Effective Demand is the title ofchapter 3 of John Maynard Keynes's book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. The principle presented in that chapter is that the aggregate demand function and the aggregate supply function intersect each other at the point of effective demand and that this point can be consistent with a state of under-employment and under-capacity utilization. Another way of expressing this, in pre-Keynesian terminology, is to say that "demand creates its own supply" which gives primacy to a shifting demand function that can be insufficient to give an economy full employment in the long term, in contrast to the Say's law which insists "supply creates its own demand" and doesn't allow the possibility of long term unemployment as the supply figure is always, by definition, a fixed amount that demand will match.