Rastafari, sometimes called Rastafarianism by outsiders, is an Abrahamic religion that developed in Jamaica during the 1930s. It is classified as both a new religious movement and a social movement by scholars of religion. There is no central authority in control of the movement and much diversity exists among practitioners, known as Rastafari or Rastas. The terms Rastafarian and Rastafarianism are often considered controversial among practitioners.

Marcus Mosiah Garvey Jr. was a Jamaican political activist. He was the founder and first President-General of the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League, through which he declared himself Provisional President of Africa. Garvey was ideologically a black nationalist and Pan-Africanist. His ideas came to be known as Garveyism.

Garveyism is an aspect of black nationalism that refers to the economic, racial and political policies of UNIA-ACL founder Marcus Garvey.

The Bobo Ashanti, also known as the Ethiopian African Black International Congress (E.A.B.I.C.), is a religious group originating in Bull Bay near Kingston, Jamaica.

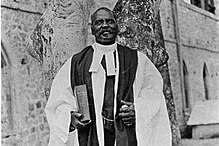

Leonard Percival Howell, also known as The Gong or G. G. Maragh, was a Jamaican religious figure. According to his biographer Hélène Lee, Howell was born into an Anglican family. He was one of the first preachers of the Rastafari movement, and is known by many as The First Rasta.

The Ethiopian Zion Coptic Church is a religious movement that originated in Jamaica during the 1940s and later spread to the United States, being incorporated in Florida in 1975. Its beliefs are based on both the Old and New testaments of the bible, as well as the teachings of Marcus Garvey, self-reliance, Afrocentricity and Ethiopianism. Their ceremonies include bible reading, chanting, and music incorporating elements from Nyahbinghi, Burru, Kumina and other indigenous traditions. The group holds many beliefs in common with the Rastafari, including the use of marijuana as a sacrament, but differ on many points, most significantly the matter of Haile Selassie's divinity.

The Ethiopian movement is a religious movement that began in southern Africa towards the end of the 19th and early 20th century, when two groups broke away from the Anglican and Methodist churches. One of the main reasons for breaking away was the growing idea that Africa had little to no history before the European colonisation of the continent, leaving many Africans upset at the prospect of their heritage and culture being erased through colonialism.

Michael George Henry OD, better known as Ras Michael, is a Jamaican reggae singer and Nyabinghi specialist. He also performs under the name of Dadawah.

The Rastafari movement in the United States echoes the Rastafari religious movement, which began in Jamaica and Ethiopia during the 1930s. Marcus Garvey, born in Jamaica, was influenced by the Ethiopian king Haile Selassie. Jamaican Rastafaris began emigrating to the United States in the 1960s and 1970s, and established communities throughout the country.

Bedwardism, more properly the Jamaica Native Baptist Free Church, was a religious movement of Jamaica.

Protestantism is the dominant religion in Jamaica. Protestants make up about 65% percent of the population. The five largest denominations in Jamaica are: The New Testament Church of God which is a part Church of God, Seventh-day Adventist, Baptist, Pentecostal and Anglican. The full list is below. Most of the Caribbean is Catholic; Jamaica's Protestantism is a legacy of missionaries that came to the island in the 18th and 19th centuries. Missionaries attempted to convert slaves to varying Protestant denominations of Moravians, Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians to name a few. As missionaries worked to convert slaves, African traditions mixed with the religion brought over by Europeans. Protestantism was associated with black nationalism in Jamaica, aiming to improve the lives of blacks who were governed by a white minority during colonial times. Today, Protestantism plays an important role in society by providing services to people in need.

Robert Athlyi Rogers, born in Anguilla, was the author of the Holy Piby, and founder of the "Afro-Athlican Constructive Church".

Black nationalism is a nationalist movement which seeks representation for black people as a distinct national identity, especially in racialized, colonial and postcolonial societies. Its earliest proponents saw it as a way to advocate for democratic representation in culturally plural societies or to establish self-governing independent nation-states for black people. Modern black nationalism often aims for the social, political, and economic empowerment of black communities within white majority societies, either as an alternative to assimilation or as a way to ensure greater representation and equality within predominantly Eurocentric or white cultures.

The Crown Colony of Jamaica and Dependencies was a British colony from 1655, when it was captured by the English Protectorate from the Spanish Empire. Jamaica became a British colony from 1707 and a Crown colony in 1866. The Colony was primarily used for sugarcane production, and experienced many slave rebellions over the course of British rule. Jamaica was granted independence in 1962.

Marley is a 2012 documentary-biographical film directed by Kevin Macdonald documenting the life of Bob Marley.

Joseph Robert Love, known as Dr. Robert Love, was a 19th-century Bahamian-born medical doctor, clergyman, teacher, journalist, politician and pan-Africanist. He lived, studied, and worked successively in the Bahamas, the United States of America, Haiti, and Jamaica. Love spent the last decades of his life in Jamaica, where he held political office, published a newspaper, and advocated for the island's black majority.

Augustown is a 2016 novel by Jamaican writer Kei Miller. Augustown was published in the UK by Weidenfeld & Nicolson in 2016 and by Pantheon Books in the US. It is Miller's third novel; he is also a poet.

Myal is an Afro-Jamaican spirituality. It developed via the creolization of African religions during the slave era in Jamaica. It incorporates ritualistic magic, spiritual possession and dancing. Unlike Obeah, its practices focus more on the connection of spirits with humans. Over time, Myal began to meld with Christian practices and created the religious tradition known as Revivalism.

The Rastafari movement developed out of the legacy of the Atlantic slave trade, in which over ten million Africans were enslaved and transported to the Americas between the 16th and 19th centuries. Once there, they were sold to European planters and forced to work on the plantations. Around a third of these transported Africans were relocated in the Caribbean, with under 700,000 being settled in Jamaica. In 1834, slavery in Jamaica was abolished after the British government passed the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. Racial prejudice nevertheless remained prevalent across Jamaican society. The overwhelming majority of Jamaica's legislative council was white throughout the 19th century, and those of African descent were treated as second-class citizens.

Free black people in Jamaica fell into two categories. Some secured their freedom officially, and lived within the slave communities of the Colony of Jamaica. Others ran away from slavery, and formed independent communities in the forested mountains of the interior. This latter group included the Jamaican Maroons, and subsequent fugitives from the sugar and coffee plantations of coastal Jamaica.