All Fools entered the historical record when the Children of the Queen's Revels performed the play at Court before King James I on 1 January 1605. Based on that fact, "the play was probably on the Blackfriars stage in 1604." [3]

The date of the play's composition is complicated by a notation in "Henslowe's Diary," the general term for the records that Philip Henslowe kept of his business at the Rose Theatre from 1591 to 1609. An undated note from the first half of 1599 records a payment to Chapman of £8 10s. for "The World Runs a Wheels & now All Fools But the Fool." [4] Some critics interpret these as two successive titles for an earlier version of All Fools, played by Henslowe's Admiral's Men at the Rose in 1599, and later revised for the Children of the Queen's Revels at Blackfriars. [5] Others, however, consider them separate plays. [3]

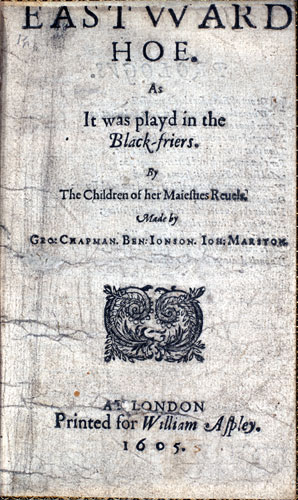

All Fools was first published in 1605, in a quarto printed by George Eld for the publisher Thomas Thorpe. [3] [6] This was the only edition of the work issued during the 17th century. (A sonnet dedicating the play to Sir Thomas Walsingham, which was printed in 1825 in an edition prepared by the noted literary forger John Payne Collier and preserved nowhere else, is now generally considered a fake.) [7]

Synopsis

Chapman based the plot of All Fools on two classical Roman comedies by Terence, the Heauton Timorumenos and the Adelphoe . [8] As to be expected with Terentian and Terence-influenced comedy, the plot of All Fools centers on two old men and their children. The two seniors are knights of Florence named Gostanzo and Marc Antonio. Gostanzo is a brashly acquisitive and manipulative old man, an "old, politique, dissembling knight" who believes that "Honesty is but a defect of wit." In contrast, Marc Antonio is a mellower-tempered gentleman who follows a course of "simple honesty."

Each of the knights has two children: Gostanzo is the father of a son, Valerio, and a daughter, Bellomora, while Marc Antonio has two sons, Fortunio and Rynaldo. Valerio has received the education appropriate to a young gentleman, though his father keeps him down on the farm, busy with the tasks of husbandry; and Bellomora is secluded at home. This inhibits the love lives of both young people. Valerio has entered into a secret marriage with the comely but poor Gratiana, yet cannot acknowledge his marriage publicly due to paternal opposition. Marc Antonio's elder son Fortunio is in love with Bellamora, but has no opportunity to court her.

The nosy Gostanzo happens to catch sight of the group of young people, and notes Valerio and Gratiana together. As the others retreat, the witty young Rynaldo persuades Gostanzo that Gratiana is actually the secret wife of his brother Fortunio. Rynaldo manipulatively presses Gostanzo to keep the secret; Gostanzo agrees...and instantly goes to Marc Antonio to inform him. Marc Antonio is skeptical that his son is secretly married; in response Gostanzo talks up a tower of speculation and possibility, in which Marc Antonio's righteous indignation drives Fortunio to run off to the wars and lose various limbs. Gostanzo works up his own solution to this non-existent problem: Fortunio and Gratiana will come to live in Gostanzo's house, and Gostanzo will persuade Fortunio of the error of his ways.

This plan, when carried out, gives the young people exactly what they want. Valerio and his wife Gratiana are under the same roof, under his father's nose; and Fortunio can woo Bellomora. Yet Gostanzo's busybody nature cannot rest; spying on his guests, he notes that his son Valerio is too affectionate with Fortunio's "wife" Gratiana. He cooks up a further plan, to send Gratiana to the house of her "father-in-law" Marc Antonio, to prevent Fortunio from being "cuckolded" in his (non-existent) marriage. Marc Antonio remains skeptical. Gostanzo is so sure he's right that when Valerio gives a deceptive confession of his marriage, Gostanzo thinks that his son is fooling with Marc Antonio and gives his son a facetious pardon for his fault.

The outcome is that once the full story comes out at the end of the play, Valerio has gained his father's public blessing of his marriage with Gratiana. Gostanzo, a self-expressed admirer of wit, has to concede his son's cleverness. Meanwhile, Fortunio has made the most of his opportunity and married Bellomora.

The play has a subplot on the topic of male jealousy: Cornelio is irrationally and excessively jealous of his faithful wife Gazetta, and quarrels with the man he thinks is her lover. He duels with and wounds the courtier Doriotto, and threatens to divorce his wife – which allows opportunities for medical humor with Pock the surgeon, and legal humor with a Notary. (The Notary even provides a specific date for the play in his divorce document: 17 November 1500.) In the end, the divorce does not occur; Cornelio admits that he was only trying to teach his wife a lesson.

In the closing tavern scene, everyone gets his share of come-uppance (except for the mild Marc Antonio). Gostanzo is forced to concede that, as Marc Antonio has put it, "too much wisdom evermore / Outshoots the truth."