Ahmad Shah Qajar was Shah of Persia (Iran) from 16 July 1909 to 15 December 1925, and the last ruling member of the Qajar dynasty.

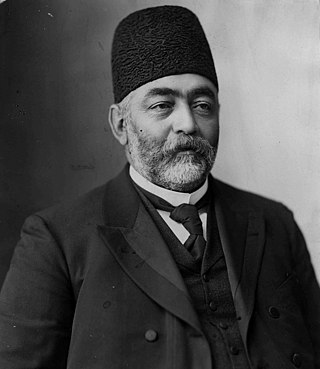

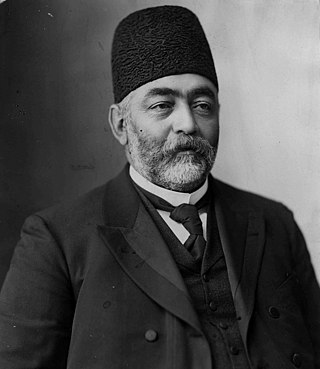

Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar Shah of Iran from 8 January 1907 to 16 July 1909. He was the sixth shah of the Qajar dynasty.

Fath-Ali Shah Qajar was the second Shah (king) of Qajar Iran. He reigned from 17 June 1797 until his death on 24 October 1834. His reign saw the irrevocable ceding of Iran's northern territories in the Caucasus, comprising what is nowadays Georgia, Dagestan, Azerbaijan, and Armenia, to the Russian Empire following the Russo-Persian Wars of 1804–1813 and 1826–1828 and the resulting treaties of Gulistan and Turkmenchay. Historian Joseph M. Upton says that he "is famous among Iranians for three things: his exceptionally long beard, his wasp-like waist, and his progeny."

Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar, was the fifth Qajar shah (king) of Iran, reigning from 1896 until his death in 1907. He is often credited with the creation of the Persian Constitution of 1906, which he approved of as one of his final actions as shah.

Naser al-Din Shah Qajar was the fourth Shah of Qajar Iran from 5 September 1848 to 1 May 1896 when he was assassinated. He was the son of Mohammad Shah Qajar and Malek Jahan Khanom and the third longest reigning monarch in Iranian history after Shapur II of the Sassanid dynasty and Tahmasp I of the Safavid dynasty. Nasser al-Din Shah had sovereign power for close to 51 years.

The Shāh Abdol-Azīm Shrine, also known as Shabdolazim, located in Rey, Iran, contains the tomb of ‘Abdul ‘Adhīm ibn ‘Abdillāh al-Hasanī. Shah Abdol Azim was a fifth generation descendant of Hasan ibn ‘Alī and a companion of Muhammad al-Taqī. He was entombed here after his death in the 9th century.

Prince Abbas Mirza Farman Farmaian Qajar (1890–1935) was an Iranian prince of the Qajar dynasty, the second son of Prince Abdol-Hossein Mirza Farmanfarma of Persia, one of the most preeminent political figures of his time and of the royal Princess Ezzat ed-Dowleh Qajar, the daughter of king Mozaffar-al-Din Shah. He was named after his great-grand father, crown prince Abbas Mirza, the son of Fath Ali Shah Qajar.

Mirzā Jahāngir Khān, also known as Mirzā Jahāngir Khān Shirāzi and Jahāngir-Khān-e Sūr-e-Esrāfil, was an Iranian writer and intellectual, and a revolutionary during the Iranian Constitutional Revolution (1905–1911). He is best known for his editorship of the progressive weekly newspaper Sur-e Esrāfil, of which he was also the founder. He was executed, at the age of 38, or 32, for his revolutionary zeal, following the successful coup d'état of Mohammad-Ali Shah Qajar in June 1908. His execution took place in Bāgh-e Shāh in Tehran, and was attended by Mohammad-Ali Shah himself. He shared this fate simultaneously with his fellow revolutionary Mirzā Nasro'llah Beheshti, better known as Malek al-Motakallemin. It has been reported that immediately before his execution he had said "Long live the constitutional government" and pointed to the ground and uttered the words "O Land, we are [being] killed for the sake of your preservation [/protection]".

Mirza Ali Asghar Khan, also known by his honorific titles of Amin al-Soltan and Atabak, served as Prime Minister of Iran under the Shah Naser al-Din, from May 1907 until his assassination in August 1907.

The Persian Constitutional Revolution, also known as the Constitutional Revolution of Iran, took place between 1905 and 1911 during the Qajar dynasty. The revolution led to the establishment of a parliament in Persia (Iran), and has been called an "epoch-making episode in the modern history of Persia".

Kamran Mirza was a Persian Prince of Qajar dynasty and third surviving son of Nasser al-Din Shah. He was the brother of Mass'oud Mirza Zell-e Soltan and Mozzafar al-Din Shah. He was also the progenitor of the Kamrani Family. He might have been Prime minister of Iran for a few days in April–May 1909, but this is not clearly referenced. Kamran Mirza also served as Iran's Commander-in-Chief, appointed in 1868 for the first time, and minister of war from 1880 to 1896 and from 1906 to 1907.

Mahmoud Afshartous, also written Afshartoos, was an Iranian general and chief of police during the government of Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh. Afshartous was abducted and killed by anti-Mossadegh conspirators led by MI6 which helped pave the way for the 1953 coup d'état.

Zarrinnaal or Zarrin Naal is the name of a dynasty of Kurdish tribal chiefs and state officials belonging to the Zarrin Kafsh tribe and originated from Sanandaj in Kurdistan Province of Iran. Their heads with the title of Beyg, Beyk or Beg (lit."lord") were the Aghas of Senneh and ruled their fiefdom during the time of four hundred years when the Safavids, Afsharids and finally Qajar dynasty reigned in Iran.

Ali Akbar Bahman was an Iranian diplomat and politician during the Qajar and Pahlavi eras.

Mohammad Taqi Mirza Hessam os-Saltaneh was a Persian Prince of the Qajar dynasty, son of Fath Ali Shah. He was Governor-General (beglerbegi) of Kermanshah and of Boroujerd.

The Khoy Khanate, also known as the Principality of Donboli, was a hereditary Kurdish khanate around Khoy and Salmas in Iran ruled by the Donboli tribe from 1210 until 1799. The khanate has been described as the most powerful khanate in the region during the second half of the 18th century. The official religion of this principality was originally Yezidism, until some rulers eventually converted to Islam. The principality has its origins under the Ayyubid dynasty and was ultimately dissolved in 1799 by Abbas Mirza. During this period, the status of principality oscillated between autonomous and independent.

The House of Bahmani, also called Bahmani-Qajar, is an aristocratic Iranian family belonging to one of the princely families of the Qajar dynasty, the ruling house that reigned Iran 1785–1925. The founder is Bahman Mirza Qajar (1810–1884), the younger brother of Mohammad Shah Qajar and formerly prince regent and governor of Azerbaijan 1841–1848.

Prince Anoushiravan Mirza "Zia' od-Dowleh" "Amir Touman" (1833-1899) was a Persian prince of the Qajar dynasty, politician, and governor.

The Iranian Enlightenment, sometimes called the first generation of intellectual movements in Iran, brought new ideas into traditional Iranian society from the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth century. During the rule of the Qajar dynasty, and especially after the defeat of Iran in its war with the Russian Empire, cultural exchanges led to the formation of new ideas among the educated class of Iran. This military defeat also encouraged the Qajar commanders to overcome Iran's backwardness. The establishment of Dar ul-Fonun, the first modern university in Iran and the arrival of foreign professors, caused the thoughts of European thinkers to enter Iran, followed by the first signs of enlightenment and intellectual movements in Iran.

Mahmud Mirza Qajar was an Iranian prince of the Qajar dynasty and the fifteenth son of Fath-Ali Shah, king (shah) of Qajar Iran. He was a patron of the arts and an accomplished calligrapher, poet, and anthologist in his own right.