The institution of slavery in the European colonies in North America, which eventually became part of the United States of America, developed due to a combination of factors. Primarily, the labor demands for establishing and maintaining European colonies resulted in the Atlantic slave trade. Slavery existed in every European colony in the Americas during the early modern period, and both Africans and indigenous peoples were targets of enslavement by Europeans during the era.

The legal institution of human chattel slavery, comprising the enslavement primarily of Africans and African Americans, was prevalent in the United States from its founding in 1776 until 1865, predominantly in the South. Slavery was established throughout European colonization in the Americas. From 1526, during the early colonial period, it was practiced in what became Britain's colonies, including the Thirteen Colonies that formed the United States. Under the law, an enslaved person was treated as property that could be bought, sold, or given away. Slavery lasted in about half of U.S. states until abolition in 1865, and issues concerning slavery seeped into every aspect of national politics, economics, and social custom. In the decades after the end of Reconstruction in 1877, many of slavery's economic and social functions were continued through segregation, sharecropping, and convict leasing. Involuntary servitude as a punishment for crime is still legal in the United States.

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract called an "indenture", may be entered voluntarily for a prepaid lump sum, as payment for some good or service, purported eventual compensation, or debt repayment. An indenture may also be imposed involuntarily as a judicial punishment. The practice has been compared to the similar institution of slavery, although there are differences.

Edmund Sears Morgan was an American historian and an authority on early American history. He was the Sterling Professor of History at Yale University, where he taught from 1955 to 1986. He specialized in American colonial history, with some attention to English history. Thomas S. Kidd says he was noted for his incisive writing style, "simply one of the best academic prose stylists America has ever produced." He covered many topics, including Puritanism, political ideas, the American Revolution, slavery, historiography, family life, and numerous notables such as Benjamin Franklin.

A headright refers to a legal grant of land given to settlers during the period of European colonization in the Americas. A "headright" includes both the grant of land and the owner that claims the land. The person who has a right to the land is the one who paid to transport people to a colony. Headrights are most notable for their role in the expansion of the Thirteen Colonies; the Virginia Company gave headrights to settlers, and the Plymouth Company followed suit. The headright system was used in several colonies, including Maryland, Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina. Most headrights were for 1 to 1,000 acres (4.0 km2) of land, and were granted to those who were willing to cross the Atlantic and help populate the colonies. Headrights were granted to anyone who would pay for the transportation costs of an indentured laborer. These land grants consisted of 50 acres (0.20 km2) for someone newly moving to the area and 100 acres (0.40 km2) for people previously living in the area. By ensuring the landowning masters had legal ownership of all land acquired, the indentured laborers after their indenture period had passed had little opportunity to procure their own land. This kept a large portion of the citizens of the Thirteen Colonies poor and led to tensions between the laborers and the landowners.

Partus sequitur ventrem was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies in the Americas which defined the legal status of children born there; the doctrine mandated that children of enslaved mothers would inherit the legal status of their mothers. As such, children of enslaved women would be born into slavery. The legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem was derived from Roman civil law, specifically the portions concerning slavery and personal property (chattels), as well as the common law of personal property; analogous legislation existed in other civilizations including Medieval Egypt in Africa and Korea in Asia.

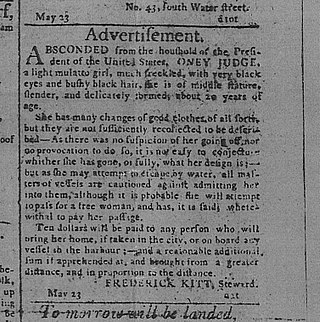

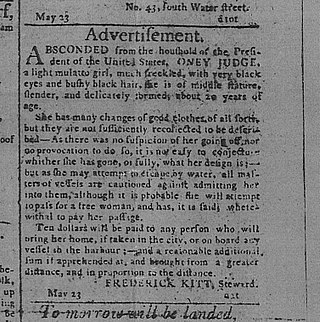

The history of George Washington and slavery reflects Washington's changing attitude toward the ownership of human beings. The preeminent Founding Father of the United States and a hereditary slaveowner, Washington became uneasy with it, though kept the opinion in private communications only. Slavery was then a longstanding institution dating back over a century in Virginia where he lived; it was also longstanding in other American colonies and in world history. Washington's will immediately freed one of his slaves, and required his remaining 123 slaves to serve his wife and be freed no later than her death; they ultimately became free one year after his own death.

The Virginia Slave Codes of 1705, were a series of laws enacted by the Colony of Virginia's House of Burgesses in 1705 regulating the interactions between slaves and citizens of the crown colony of Virginia. The enactment of the Slave Codes is considered to be the consolidation of slavery in Virginia, and served as the foundation of Virginia's slave legislation. All servants from non-Christian lands became slaves. There were forty one parts of this code each defining a different part and law surrounding the slavery in Virginia. These codes overruled the other codes in the past and any other subject covered by this act are canceled.

John Casor, a servant in Northampton County in the Colony of Virginia, in 1655 became one of the first people of African descent in the Thirteen Colonies to be enslaved for life as a result of a civil suit.

Anthony Johnson was a man from Angola who achieved wealth in the early 17th-century Colony of Virginia. Held as an "indentured servant" in 1621, he earned his freedom after several years and was granted land by the colony.

Living in a wide range of circumstances and possessing the intersecting identity of both black and female, enslaved women of African descent had nuanced experiences of slavery. Historian Deborah Gray White explains that "the uniqueness of the African-American female's situation is that she stands at the crossroads of two of the most well-developed ideologies in America, that regarding women and that regarding the Negro." Beginning as early on in enslavement as the voyage on the Middle Passage, enslaved women received different treatment due to their gender. In regard to physical labor and hardship, enslaved women received similar treatment to their male counterparts, but they also frequently experienced sexual abuse at the hand of their enslavers who used stereotypes of black women's hypersexuality as justification.

The trafficking of enslaved Africans to what became New York began as part of the Dutch slave trade. The Dutch West India Company trafficked eleven enslaved Africans to New Amsterdam in 1626, with the first slave auction held in New Amsterdam in 1655. With the second-highest proportion of any city in the colonies, more than 42% of New York City households enslaved African people by 1703, often as domestic servants and laborers. Others worked as artisans or in shipping and various trades in the city. Enslaved Africans were also used in farming on Long Island and in the Hudson Valley, as well as the Mohawk Valley region.

When the Dutch and Swedes established colonies in the Delaware Valley of what is now Pennsylvania, in North America, they quickly imported enslaved Africans for labor; the Dutch also transported them south from their colony of New Netherland. Enslavement was documented in this area as early as 1639. William Penn and the colonists who settled in Pennsylvania tolerated slavery. Still, the English Quakers and later German immigrants were among the first to speak out against it. Many colonial Methodists and Baptists also opposed it on religious grounds. During the Great Awakening of the late 18th century, their preachers urged slaveholders to free their slaves. High British tariffs in the 18th century discouraged the importation of additional slaves, and encouraged the use of white indentured servants and free labor.

Elizabeth Key Grinstead (or Greenstead) (c. 1630 or 1632 – 1665) was one of the first Black people in the Thirteen Colonies to sue for freedom from slavery and win. Key won her freedom and that of her infant son, John Grinstead, on July 21, 1656, in the Colony of Virginia.

Slavery in Maryland lasted over 200 years, from its beginnings in 1642 when the first Africans were brought as slaves to St. Mary's City, to its end after the Civil War. While Maryland developed similarly to neighboring Virginia, slavery declined in Maryland as an institution earlier, and it had the largest free black population by 1860 of any state. The early settlements and population centers of the province tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay. Maryland planters cultivated tobacco as the chief commodity crop, as the market for cash crops was strong in Europe. Tobacco was labor-intensive in both cultivation and processing, and planters struggled to manage workers as tobacco prices declined in the late 17th century, even as farms became larger and more efficient. At first, indentured servants from England supplied much of the necessary labor but, as England's economy improved, fewer came to the colonies. Maryland colonists turned to importing indentured and enslaved Africans to satisfy the labor demand.

Slavery in Virginia began with the capture and enslavement of Native Americans during the early days of the English Colony of Virginia and through the late eighteenth century. They primarily worked in tobacco fields. Africans were first brought to colonial Virginia in 1619, when 20 Africans from present-day Angola arrived in Virginia aboard the ship The White Lion.

Slaves in the United States were often subjected to sexual abuse and rape, the denial of education, and punishments like whippings. Families were often split up by the sale of one or more members, usually never to see or hear of each other again.

John Punch was an Angolan-born resident of the colony of Virginia who became its first legally enslaved person in British colonial America under criminal law. In contrast, John Casor became the first legally enslaved person of the colonies under civil law, having committed no crime.

White Southerners, are White Americans from the Southern United States, originating from the various waves of Northwestern European immigration to the region beginning in the 17th century. A significant motivator in the creation of a unified white Southern identity was white supremacism.

Irish indentured servants were Irish people who became indentured servants in territories under the control of the British Empire, such as the British West Indies, British North America and later Australia.