Geghard is a medieval monastery in the Kotayk province of Armenia, being partially carved out of the adjacent mountain, surrounded by cliffs. It is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site with enhanced protection status.

Sevanavank is a monastic complex located on a peninsula at the northwestern shore of Lake Sevan in the Gegharkunik Province of Armenia, not far from the town of Sevan. Initially the monastery was built at the southern shore of a small island. After the artificial draining of Lake Sevan, which started in the era of Joseph Stalin, the water level fell about 20 metres, and the island transformed into a peninsula. At the southern shore of this newly created peninsula, a guesthouse of the Armenian Writers' Union was built. The eastern shore is occupied by the Armenian president's summer residence, while the monastery's still active seminary moved to newly constructed buildings at the northern shore of the peninsula.

Kitbuqa Noyan, also spelled Kitbogha, Kitboga, or Ketbugha, was an Eastern Christian of the Naimans, a group that was subservient to the Mongol Empire. He was a lieutenant and confidant of the Mongol Ilkhan Hulagu, assisting him in his conquests in the Middle East including the sack of Baghdad in 1258. When Hulagu took the bulk of his forces back with him to attend a ceremony in Mongolia, Kitbuqa was left in control of Syria, and was responsible for further Mongol raids southwards towards the Mamluk Sultanate based in Cairo. He was killed at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260.

Nakharar was a hereditary title of the highest order given to houses of the ancient and medieval Armenian nobility.

The Orbelian lords of the province of Syunik were a noble family of Armenia, with a long history of political influence documented in inscriptions throughout the provinces of Vayots Dzor and Syunik, and recorded by the family historian Bishop Stepanos in his 1297 History of Syunik.

Haghpat Monastery, also known as Haghpatavank, is a medieval monastery complex in Haghpat, Armenia, built between the 10th and 13th century.

Hasan-Jalalyan is a medieval Armenian dynasty that ruled over parts of the South Caucasus. From the early thirteenth century, the family held sway in Khachen in what are now the regions of lower Karabakh, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Syunik in modern Armenia. The family was founded by Hasan-Jalal Dawla, an Armenian feudal prince from Khachen. The Hasan-Jalalyans maintained their autonomy over the course of several centuries of nominal foreign domination by the Seljuk Turks, Persians and Mongols. They, along with the other Armenian princes and meliks of Khachen, saw themselves as holding the last bastion of Armenian independence in the region.

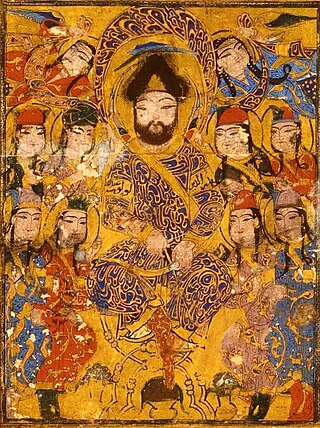

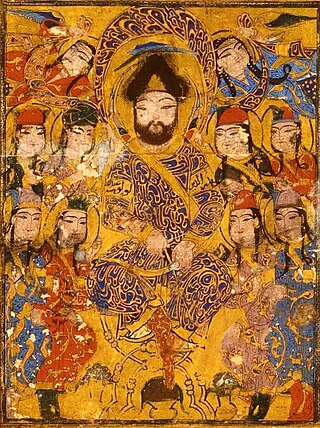

Badr al-Din Lu'lu' was successor to the Zengid emirs of Mosul, where he governed in variety of capacities from 1234 to 1259 following the death of Nasir ad-Din Mahmud. He was the founder of the short-lived Luluid dynasty. Originally a slave of the Zengid ruler Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I, he was the first Middle-Eastern mamluk to transcend servitude and become an emir in his own right, founding the dynasty of the Lu'lu'id emirs (1234-1262), and anticipating the rise of the Bahri Mamluks of the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt by twenty years. He preserved control of al-Jazira through a series of tactical submissions to larger neighboring powers, at various times recognizing Ayyubid, Rûmi Seljuq, and Mongol overlords. His surrender to the Mongols after 1243 temporarily spared Mosul the destruction experienced by other settlements in Mesopotamia.

Arghun Agha, also Arghun Aqa or Arghun the Elder was a Mongol noble of the Oirat clan in the 13th century. He was a governor in the Mongol-controlled area of Persia from 1243 to 1255, before the Ilkhanate was created by Hulagu. Arghun Agha was in control of the four districts of eastern and central Persia, as decreed by the great khan Möngke Khan.

Zakarid Armenia alternatively known as the Zakarid Period, describes a historical period in the Middle Ages during which the Armenian vassals of the Kingdom of Georgia were ruled by the Zakarid-Mkhargrzeli dynasty. The city of Ani was the capital of the princedom. The Zakarids were vassals to the Bagrationi dynasty in Georgia, but frequently acted independently and at times titled themselves as kings. In 1236, they fell under the rule of the Mongol Empire as a vassal state with local autonomy.

Spitakavor Monastery, is a 14th-century Armenian monastic complex, 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) north of Vernashen village, near the town of Yeghegnadzor of Vayots Dzor Province, Armenia.

Tanahat Monastery, is an 8th-century monastery 7 km south-east of Vernashen village in the Vayots Dzor Province of Armenia. It was built between the 8th and 13th centuries. The monastery was also called the Red Monastery because it was built of red stone. Tanahat monastery was built on the site of a pagan temple, which was dedicated to the Armenian goddess Anahit. A Christian temple was founded here in the 5th century. The early medieval cemetery is scattered next to the monastery. Tanahat Monastery functioned until the late Middle Ages and is now in good condition. According to the historian Stepanos Archbishop Orbelyan, in 735 the body of Stepanos Syunetsi was buried in Tanade monastery and a small chapel was built over the grave.

Avag Zakarian was an Armenian noble of the Zakarid line, and a Court official of the Kingdom of Georgia, as atabeg and amirspasalar of Georgia from 1227 to 1250.

Zakare III Zakarian was a 13th century Armenian noble and a Court official of the Kingdom of Georgia, holding the position of amirspasalar (Commander-in-Chief) for the Georgian army.

Prosh Khaghbakian, also known as Hasan Prosh, was an Armenian prince who was a vassal of the Zakarid princes of Armenia. He was a member of the Khaghbakian dynasty, which is also known as the Proshian dynasty after him. He was the supreme commander (sparapet) of the Zakarid army from 1223 to 1284, succeeding his father Vasak. He was one of the main Greater Armenian lords to execute the alliance between his suzerain the Georgian king David Ulu and the Mongol Prince Hulagu, during the Mongol conquest of Middle East (1258–1260).

Shahnshah Zakarian was a member of the Armenian Zakarid dynasty, and a Court official of the Kingdom of Georgia, holding the office of amirspasalar (Commander-in-Chief) of the Georgian army. He was the son of Zakare II Zakarian, and the father of Zakare III Zakarian, who participated to the Siege of Baghdad in 1258.

The Proshyan dynasty, also Khaghbakians or Xaghbakian-Proshians, was a family of the Armenian nobility, named after its founder Prince Prosh Khaghbakian. The dynasty was a vassal of Zakarid Armenia during the 13th–14th century CE, established as nakharar feudal lords as a reward for their military successes. Zakarid Armenia was itself vassal of the Kingdom of Georgia from 1201, effectively falling under Mongol control after 1236, while Georgian rule only remained nominal. The Proshyans were princes of Bjni, Garni, Geghard and Noravank. The family prospered as an ally of the Mongols, following the Mongol invasions of Armenia and Georgia, as did the Zakarians and Orbelians. Despite heavy Mongol taxes, they benefited from trade routes to China under the control of the Mongols, and built many magnificent churches and monasteries.

Grigor Khaghbakian was a Prince of the Armenian Khaghbakian family in the province of Zakarid Armenia, Kingdom of Georgia. Together with his wife Zaz, he built the Surp Stepanos church at Aghjots Vank in 1217.

The Kingdom of Georgia from 1256 to 1329, sometimes called the Kingdom of Eastern Georgia was the official prolongation of the Kingdom of Georgia from 1256 to 1329, but limited in its rule to the geographical areas of central and eastern Georgia, while the western part of the country temporarily seceded to form the Kingdom of Western Georgia under its own line of kings. The secession followed a transitional period when the rule of the Kingdom of Georgia was jointly assumed by the cousins David VI and David VII from 1246 to 1256. The entity split into two parts when David VI, revolting from the Mongol hegemony, seceded in the western half of the kingdom and formed the Kingdom of Western Georgia in 1256. David VII was relegated to the rule of Eastern Georgia. During his reign, Eastern Georgia went into further decline under the Mongol overlordship.

The Siege of Mayyafariqin in 1259–1260 was a Mongol siege against the last Ayyubid ruler Al-Kamil Muhammad in his city of Mayyāfāriqīn. The Siege of Mayyāfāriqīn closely followed the 1258 Siege of Baghdad and marked the beginning of the Mongol campaigns in Syria.