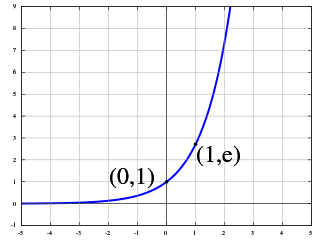

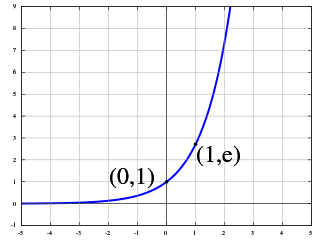

In mathematics, the exponential function is the unique real function which maps zero to one and has a derivative equal to its value. The exponential of a variable is denoted or , with the two notations used interchangeably. It is called exponential because its argument can be seen as an exponent to which a constant number e ≈ 2.718, the base, is raised. There are several other definitions of the exponential function, which are all equivalent although being of very different nature.

In finance, discounting is a mechanism in which a debtor obtains the right to delay payments to a creditor, for a defined period of time, in exchange for a charge or fee. Essentially, the party that owes money in the present purchases the right to delay the payment until some future date. This transaction is based on the fact that most people prefer current interest to delayed interest because of mortality effects, impatience effects, and salience effects. The discount, or charge, is the difference between the original amount owed in the present and the amount that has to be paid in the future to settle the debt.

The net present value (NPV) or net present worth (NPW) is a way of measuring the value of an asset that has cashflow by adding up the present value of all the future cash flows that asset will generate. The present value of a cash flow depends on the interval of time between now and the cash flow because of the Time value of money. It provides a method for evaluating and comparing capital projects or financial products with cash flows spread over time, as in loans, investments, payouts from insurance contracts plus many other applications.

In economics and finance, present value (PV), also known as present discounted value(PDV), is the value of an expected income stream determined as of the date of valuation. The present value is usually less than the future value because money has interest-earning potential, a characteristic referred to as the time value of money, except during times of negative interest rates, when the present value will be equal or more than the future value. Time value can be described with the simplified phrase, "A dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow". Here, 'worth more' means that its value is greater than tomorrow. A dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow because the dollar can be invested and earn a day's worth of interest, making the total accumulate to a value more than a dollar by tomorrow. Interest can be compared to rent. Just as rent is paid to a landlord by a tenant without the ownership of the asset being transferred, interest is paid to a lender by a borrower who gains access to the money for a time before paying it back. By letting the borrower have access to the money, the lender has sacrificed the exchange value of this money, and is compensated for it in the form of interest. The initial amount of borrowed funds is less than the total amount of money paid to the lender.

In finance and economics, interest is payment from a debtor or deposit-taking financial institution to a lender or depositor of an amount above repayment of the principal sum, at a particular rate. It is distinct from a fee which the borrower may pay to the lender or some third party. It is also distinct from dividend which is paid by a company to its shareholders (owners) from its profit or reserve, but not at a particular rate decided beforehand, rather on a pro rata basis as a share in the reward gained by risk taking entrepreneurs when the revenue earned exceeds the total costs.

The time value of money refers to the fact that there is normally a greater benefit to receiving a sum of money now rather than an identical sum later. It may be seen as an implication of the later-developed concept of time preference.

The weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is the rate that a company is expected to pay on average to all its security holders to finance its assets. The WACC is commonly referred to as the firm's cost of capital. Importantly, it is dictated by the external market and not by management. The WACC represents the minimum return that a company must earn on an existing asset base to satisfy its creditors, owners, and other providers of capital, or they will invest elsewhere.

Stock valuation is the method of calculating theoretical values of companies and their stocks. The main use of these methods is to predict future market prices, or more generally, potential market prices, and thus to profit from price movement – stocks that are judged undervalued are bought, while stocks that are judged overvalued are sold, in the expectation that undervalued stocks will overall rise in value, while overvalued stocks will generally decrease in value. A target price is a price at which an analyst believes a stock to be fairly valued relative to its projected and historical earnings.

Rational pricing is the assumption in financial economics that asset prices – and hence asset pricing models – will reflect the arbitrage-free price of the asset as any deviation from this price will be "arbitraged away". This assumption is useful in pricing fixed income securities, particularly bonds, and is fundamental to the pricing of derivative instruments.

Bond valuation is the process by which an investor arrives at an estimate of the theoretical fair value, or intrinsic worth, of a bond. As with any security or capital investment, the theoretical fair value of a bond is the present value of the stream of cash flows it is expected to generate. Hence, the value of a bond is obtained by discounting the bond's expected cash flows to the present using an appropriate discount rate.

In finance, the duration of a financial asset that consists of fixed cash flows, such as a bond, is the weighted average of the times until those fixed cash flows are received. When the price of an asset is considered as a function of yield, duration also measures the price sensitivity to yield, the rate of change of price with respect to yield, or the percentage change in price for a parallel shift in yields.

In finance, bond convexity is a measure of the non-linear relationship of bond prices to changes in interest rates, and is defined as the second derivative of the price of the bond with respect to interest rates. In general, the higher the duration, the more sensitive the bond price is to the change in interest rates. Bond convexity is one of the most basic and widely used forms of convexity in finance. Convexity was based on the work of Hon-Fei Lai and popularized by Stanley Diller.

Actuarial notation is a shorthand method to allow actuaries to record mathematical formulas that deal with interest rates and life tables.

In finance, leverage, also known as gearing, is any technique involving borrowing funds to buy an investment.

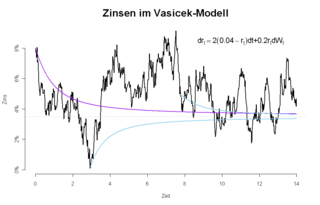

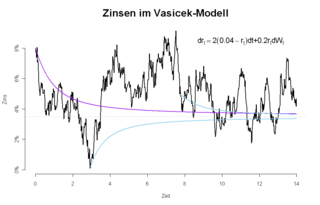

In finance, the Vasicek model is a mathematical model describing the evolution of interest rates. It is a type of one-factor short-rate model as it describes interest rate movements as driven by only one source of market risk. The model can be used in the valuation of interest rate derivatives, and has also been adapted for credit markets. It was introduced in 1977 by Oldřich Vašíček, and can be also seen as a stochastic investment model.

In finance, return is a profit on an investment. It comprises any change in value of the investment, and/or cash flows which the investor receives from that investment over a specified time period, such as interest payments, coupons, cash dividends and stock dividends. It may be measured either in absolute terms or as a percentage of the amount invested. The latter is also called the holding period return.

Fixed-income attribution is the process of measuring returns generated by various sources of risk in a fixed income portfolio, particularly when multiple sources of return are active at the same time.

In finance, a T-forward measure is a pricing measure absolutely continuous with respect to a risk-neutral measure, but rather than using the money market as numeraire, it uses a bond with maturity T. The use of the forward measure was pioneered by Farshid Jamshidian (1987), and later used as a means of calculating the price of options on bonds.

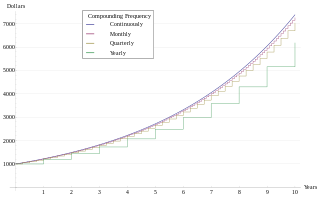

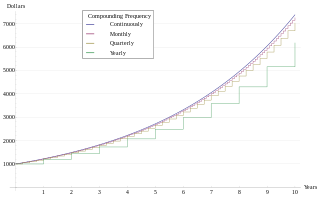

Analogous to continuous compounding, a continuous annuity is an ordinary annuity in which the payment interval is narrowed indefinitely. A (theoretical) continuous repayment mortgage is a mortgage loan paid by means of a continuous annuity.

In investment, an annuity is a series of payments made at equal intervals. Examples of annuities are regular deposits to a savings account, monthly home mortgage payments, monthly insurance payments and pension payments. Annuities can be classified by the frequency of payment dates. The payments (deposits) may be made weekly, monthly, quarterly, yearly, or at any other regular interval of time. Annuities may be calculated by mathematical functions known as "annuity functions".