Charles II was King of Spain from 1665 to 1700. The last monarch from the House of Habsburg, which had ruled Spain since 1516, he died without children, leading to a European conflict over his successor.

The Viceroyalty of Peru, officially known as the Kingdom of Peru, was a Spanish imperial provincial administrative district, created in 1542, that originally contained modern-day Peru and most of the Spanish Empire in South America, governed from the capital of Lima. Along with the Viceroyalty of New Spain, Peru was one of two Spanish viceroyalties in the Americas from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries.

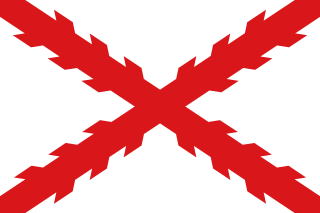

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered in the European Age of Discovery. It achieved a global scale, controlling vast portions of the Americas, Africa, various islands in Asia and Oceania, as well as territory in other parts of Europe. It was one of the most powerful empires of the early modern period, becoming known as "the empire on which the sun never sets". At its greatest extent in the late 1700s and early 1800s, the Spanish Empire covered over 13 million square kilometres, making it one of the largest empires in history.

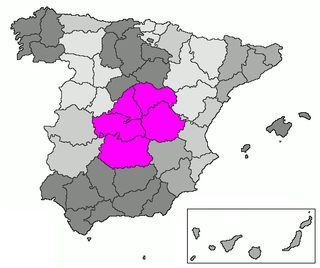

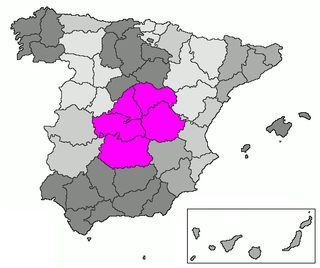

New Castile is a historic region of Spain. It roughly corresponds to the medieval Moorish Taifa of Toledo, taken during the Reconquista of the peninsula by Christians and thus becoming the southern part of Castile. The extension of New Castile was formally defined after the 1833 territorial division of Spain as the sum of the following provinces: Ciudad Real, Cuenca, Guadalajara, Madrid and Toledo.

The University of Salamanca is a public research university in Salamanca, Spain. Founded in 1218 by King Alfonso IX, it is the oldest university in the Hispanic world and one of the oldest in the world in continuous operation. It has over 30,000 students from 50 different nationalities.

Habsburg Spain refers to Spain and the Hispanic Monarchy, also known as the Catholic Monarchy, in the period from 1516 to 1700 when it was ruled by kings from the House of Habsburg. It had territories around the world, including modern-day Spain, a piece of south-eastern France, eventually Portugal and many other lands outside the Iberian Peninsula, including in the Americas and Asia. In this period the Spanish Empire was at the zenith of its influence and power. It then expanded to include territories over the five continents, consisting of much of the American continent and islands thereof, the West Indies in the Americas, the Low Countries, Italian territories and parts of France in Europe and the Philippines and other possessions in Southeast Asia. The period of Spanish history has also been referred to as the "Age of Expansion".

The Asiento de Negros was a monopoly contract between the Spanish Crown and various merchants for the right to provide enslaved Africans to colonies in the Spanish Americas. The Spanish Empire rarely engaged in the transatlantic slave trade directly from Africa itself, choosing instead to contract out the importation to foreign merchants from nations more prominent in that part of the world, typically Portuguese and Genoese, but later the Dutch, French, and British. The Asiento did not concern French or British Caribbean, or Brazil, but only Spanish America.

The Iberian Union is a historiographical term used to describe the personal union of the Kingdom of Portugal with the Monarchy of Spain, which in turn was itself the dynastic union of the crowns of Castile and Aragon, and of their respective colonial empires, that existed between 1580 and 1640 and brought the entire Iberian Peninsula except Andorra, as well as Portuguese and Spanish overseas possessions, under the Spanish Habsburg monarchs Philip II, Philip III, and Philip IV. The union began after the Portuguese succession crisis of 1580 and the ensuing War of the Portuguese Succession, and lasted until the Portuguese Restoration War, during which the House of Braganza was established as Portugal's new ruling dynasty with the acclamation of John IV as the new king of Portugal.

Leonese is a set of vernacular Romance language varieties currently spoken in northern and western portions of the historical region of León in Spain, the village of Riudenore and Guadramil in Portugal, sometimes considered another language. In the past, it was spoken in a wider area, including most of the historical region of Leon. The current number of Leonese speakers is estimated at 20,000 to 50,000. Spanish is now the predominant language in the area.

Thomas of Villanova, OSA, born Tomás García y Martínez, was a Spanish friar of the Order of Saint Augustine who was a noted preacher, ascetic and religious writer of his day. He became an archbishop who was famous for the extent of his care for the poor of his see.

The Crown of Castile was a medieval polity in the Iberian Peninsula that formed in 1230 as a result of the third and definitive union of the crowns and, some decades later, the parliaments of the kingdoms of Castile and León upon the accession of the then Castilian king, Ferdinand III, to the vacant Leonese throne. It continued to exist as a separate entity after the personal union in 1469 of the crowns of Castile and Aragon with the marriage of the Catholic Monarchs up to the promulgation of the Nueva Planta decrees by Philip V in 1716.

Fernando de Alencastre Noroña y Silva, 1st Duke of Linares, GE was a Spanish nobleman and military officer. He also served as Viceroy of New Spain, from January 15, 1711 to August 15, 1716.

Lope de Barrientos (1382–1469), sometimes called Obispo Barrientos, was a powerful clergyman and statesman of the Crown of Castile during the 15th century, although his prominence and the influence he wielded during his lifetime is not a subject of common study in Spanish history.

Gabriel von Salamanca was a Spanish nobleman who served as general treasurer and archchancellor of the Habsburg archduke Ferdinand I of Austria from 1521 to 1526. He was elevated to a Count of Ortenburg in 1524.

The history of Lima, the capital of Peru, began with its foundation by Francisco Pizarro on January 18, 1535. The city was established on the valley of the Rímac River in an area populated by the Ichma polity. It became the capital of the Viceroyalty of Peru and site of a Real Audiencia in 1543. In the 17th century, the city prospered as the center of an extensive trade network despite damage from earthquakes and the threat of pirates. However, prosperity came to an end in the 18th century due to an economic downturn and the Bourbon Reforms.

The Region of León, Leonese region or Leonese Country is a historic territory defined by the 1833 Spanish administrative organisation. The Leonese region encompassed the provinces of Salamanca, Zamora, and León, now part of the modern Spanish autonomous community of Castile and León. As is the case with other historical regions, and continuing with centuries of history, the inhabitants of the Leonese region are still called Leonese. Even today, according with official autonomous government, the historical territorial adjective is used in addition with the modern annexed territory, the rest of Old Castile, being "Castilians and Leonese".

Habsburg Spain was at the height of its power and cultural influence at the beginning of the 17th century, but military, political, and economic difficulties were already being discussed within Spain. In the coming decades these difficulties grew and saw France gradually taking Spain's place as Europe's leading power through the later half of the century. Many different factors, including the decentralized political nature of Spain, inefficient taxation, a succession of weak kings, power struggles in the Spanish court and a tendency to focus on the American colonies instead of Spain's domestic economy, all contributed to the decline of the Habsburg rule of Spain.

The Polysynodial System, Polysynodial Regime or System of Councils was the way of organization of the composite monarchy ruled by the Catholic Monarchs and the Spanish Habsburgs, which entrusted the central administration in a group of collegiate bodies (councils) already existing or created ex novo. Most of the councils were formed by lawyers trained in academic study of Roman law. After its creation in 1521, the Council of State, chaired by the monarch and formed by the high nobility and clergy, became the supreme body of the monarchy. The polysynodial system met its demise in the early 18th century in the wake of the promulgation of the Nueva Planta decrees by the incoming Bourbon dynasty, which organized a system underpinned by Secretaries of State.

The Treaty of Madrid, also known as the Earl of Sandwich's Treaty, was signed on 23 May, 1667 by England and Spain. It was one of a series of agreements made in response to French expansion under King Louis XIV.

The decline of Spain was the gradual process of financial and military exhaustion and attrition and suffered by metropolitan Spain throughout the 17th century, in particular when viewed in comparison with ascendant rival powers of France and England. The decline occurred during the reigns of the last kings of Habsburg Spain: Philip III, Philip IV and Charles II. Concurrent with the military and economic issues there was a depopulation in metropolitan Spain. The Spanish decline was a historical process simultaneous to the purpoted general crisis of the 17th century that swept most of Eurasia, but which was especially serious for Spain.