Gregorio Allegri was a Catholic priest and Italian composer of the Roman School and brother of Domenico Allegri; he was also a singer. He was born and died in Rome. He is chiefly known for his Miserere for two choirs.

The magic lantern, also known by its Latin name lanterna magica, was an early type of image projector that used pictures—paintings, prints, or photographs—on transparent plates, one or more lenses, and a light source. Because a single lens inverts an image projected through it, slides were inserted upside down in the magic lantern, rendering the projected image correctly oriented.

Athanasius Kircher was a German Jesuit scholar and polymath who published around 40 major works of comparative religion, geology, and medicine. Kircher has been compared to fellow Jesuit Roger Joseph Boscovich and to Leonardo da Vinci for his vast range of interests, and has been honoured with the title "Master of a Hundred Arts". He taught for more than 40 years at the Roman College, where he set up a wunderkammer. A resurgence of interest in Kircher has occurred within the scholarly community in recent decades.

Johann Jakob Froberger was a German Baroque composer, keyboard virtuoso, and organist. Among the most famous composers of the era, he was influential in developing the musical form of the suite of dances in his keyboard works. His harpsichord pieces are highly idiomatic and programmatic.

Johann Caspar Kerll was a German baroque composer and organist. He is also known as Kerl, Gherl, Giovanni Gasparo Cherll and Gaspard Kerle.

Johann David Heinichen was a German Baroque composer and music theorist who brought the musical genius of Venice to the court of Augustus II the Strong in Dresden. After he died, Heinichen's music attracted little attention for many years. As a music theorist, he is credited as one of the inventors of the circle of fifths.

Gaspar Schott was a German Jesuit and scientist, specializing in the fields of physics, mathematics and natural philosophy, and known for his industry.

The doctrine of the affections, also known as the doctrine of affects, doctrine of the passions, theory of the affects, or by the German term Affektenlehre was a theory in the aesthetics of painting, music, and theatre, widely used in the Baroque era (1600–1750). Literary theorists of that age, by contrast, rarely discussed the details of what was called "pathetic composition", taking it for granted that a poet should be required to "wake the soul by tender strokes of art". The doctrine was derived from ancient theories of rhetoric and oratory. Some pieces or movements of music express one Affekt throughout; however, a skillful composer like Johann Sebastian Bach could express different affects within a movement.

Johann Paul Schor (1615–1674), known in Rome as Giovanni Paolo Tedesco, was an Austrian artist. He was the preeminent designer of decorative arts in Baroque Rome, providing drawings for state beds, fireworks, coaches, silver, textiles and even banquet setpieces executed in sugar. His numerous drawings have often been attributed in the past to Bernini.

The stylus fantasticus is a style of early baroque music, especially for the instrumental music.

A cat organ, also called cat piano, is a hypothetical musical instrument which consists of a line of cats fixed in place with their tails stretched out underneath a keyboard so that they cry out when a key is pressed. The cats would be arranged according to the natural tone of their voices.

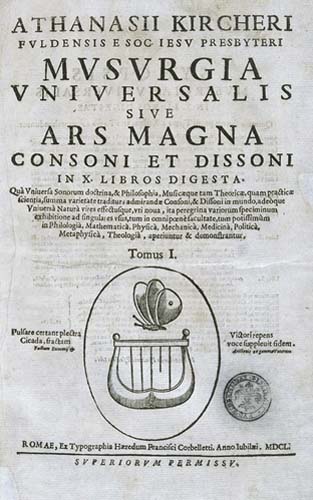

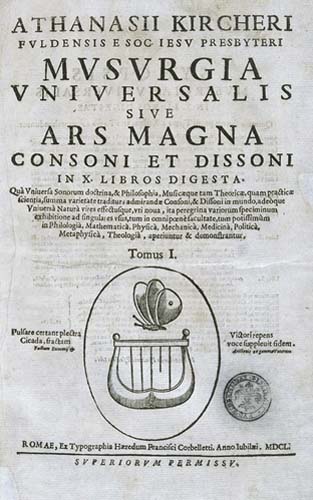

Musurgia Universalis, sive Ars Magna Consoni et Dissoni is a 1650 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was printed in Rome by Ludovico Grignani and dedicated to Archduke Leopold Wilhelm of Austria. It was a compendium of ancient and contemporary thinking about music, its production and its effects. It explored, in particular, the relationship between the mathematical properties of music with health and rhetoric. The work complements two of Kircher's other books: Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica had set out the secret underlying coherence of the universe and Ars Magna Lucis et Umbrae had explored the ways of knowledge and enlightenment. What Musurgia Universalis contained, through its exploration of dissonance within harmony, was an explanation of the presence of evil in the world.

Johann (Johannes) Speth was a German organist and composer. He was born in Speinshart, some 150 km from Nuremberg, but spent most of his life in Augsburg, where he worked as cathedral organist for two years. His only surviving music is a 1693 collection, Ars Magna Consoni et Dissoni, which includes toccatas, Magnificat versets and variations in the south German style.

Kunstkammer is the title of Jeffrey Ching's Fifth Symphony, composed in Berlin from 12 October 2004 to 6 February 2005, and revised in December 2005

John Birchensha (c.1605–1681) was an English Baroque music theorist. He presented at the Royal Society and made an impression on its members in the 1660s and 1670s.

The Organum Mathematicum was an information device or teaching machine that was invented by the Jesuit polymath and scholar Athanasius Kircher in the middle of the 17th century. With proper instruction and use, the device could assist in a wide assortment of calculations, including arithmetic, cryptography, and music.

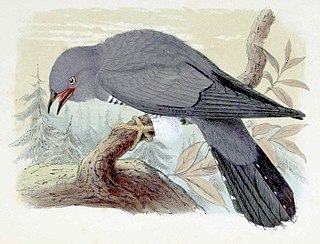

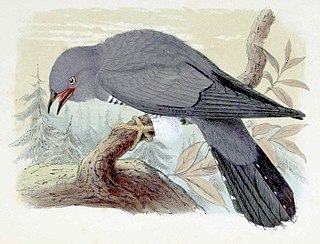

Birdsong has played a role in Western classical music since at least the 14th century, when composers such as Jean Vaillant quoted birdsong in some of their compositions. Among the birds whose song is most often used in music are the nightingale and the cuckoo.

Phonurgia Nova is a 1673 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It is notable for being the first book ever dedicated entirely to the science of acoustics, and for containing the earliest description of an aeolian harp. It was dedicated to the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I and printed in Kempten by Rudoph Dreherr.

Polygraphia nova et universalis ex combinatoria arte directa is a 1663 work by the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher. It was one of Kircher's most highly regarded works and his only complete work on the subject of cryptography, although he made passing references to the topic elsewhere. The book was distributed as a private gift to selected European rulers, some of who also received an arca steganographica, a presentation chest containing wooden tallies used to encrypt and decrypt codes.

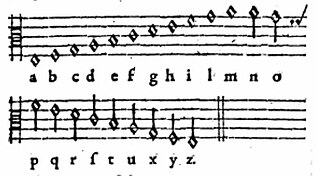

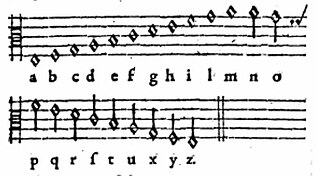

In cryptography, a music cipher is an algorithm for the encryption of a plaintext into musical symbols or sounds. Music-based ciphers are related to, but not the same as musical cryptograms. The latter were systems used by composers to create musical themes or motifs to represent names based on similarities between letters of the alphabet and musical note names, such as the BACH motif. Whereas music ciphers were systems typically used by cryptographers to hide or encode messages for reasons of secrecy or espionage.