The Athenian Band Cup (MET 17.230.5) is an Attic Greek kylix attributed to the Oakeshott Painter. [1] It is further classified as a band cup, a type of Little-Master cup.

The Athenian Band Cup (MET 17.230.5) is an Attic Greek kylix attributed to the Oakeshott Painter. [1] It is further classified as a band cup, a type of Little-Master cup.

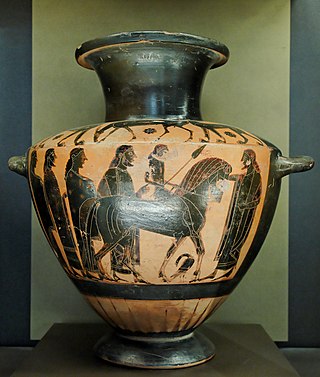

This terracotta band cup, or kylix, is 16.4 cm high and has a diameter of 28.4 cm. At present, it is exhibited in Gallery 155 (Greek Art: Sixth Century B.C.) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. [2]

The band serves as a miniature frieze, on one side showing the return of Hephaistos to Olympus, and on the other the wine god Dionysus with his wife, Ariadne.

Dionysus is indicated by his holding of a band cup, his long beard, and the thyrsus appearing staff or ivy vine. Ariadne has a shared gaze with Dionysus on the side featuring their encounter, and is the only female depicted wearing a mantle. In the other side of the cup, Hephaistos is depicted on his mule, or horse, being led by Dionysus, just as in the archaic story. The mule is shown to have an erect penis and all of the satyrs are depicted with obnoxiously long, erect penises, adding toward the theme of sexual excitement and celebration. Such themes were commonly seen on band cups used in symposiums. Both of these main scenes are surrounded by satyrs and maenads, who are depicted in a rhythmic dance.

A single figure stares at the viewer of the artwork; it is a satyr that can be found behind Hephaistos' mule. The outwardly facing satyr invites the viewer to become a participant in the scene of dancing maenads, which were similar to girls who could be seen dancing at a party. [3] The on looking satyr is a common element in subsequent versions 'Return of Hepaistos' artworks, as can be seen in similarly depicted works, such as the column krater ascribed to Lydos. [4] [5]

The band cup is often depicted with imagery of Dionysus and served as a vessel used to hold wine at parties. [3] Exploiting the circumstance in which band cups would exclusively be used, the imagery acts as encouragement, in addition to the wine, to engage in similar acts in the real world. [3]

This band cup shows an uninhibited procession, a common depiction of Dionysian myth. [6]

Author Mary Moore discusses the importance of the viewer facing Satyr, being that it brings attention to the scene of Hephaistos and Dionysus, in which these two figures have their gazes fixated on each other which reflects the significance of their interaction. [6] Author Anne Mackay elaborates on the decision artists who chose to depict outwardly facing figures as not simply a traditional motif, but as technique to direct viewer's attention and in which connected the world the artist's figure inhabits to the real world of the viewer. [4] Furthermore, the outwardly facing satyr invites the viewer to become a participant in the scene of dancing maenads, which were similar to girls who could be seen dancing at a party. [3] The gaze of the outwardly facing figure is a classic example of breaking the fourth wall, and the gaze often urges the viewer to share the figure's emotion. [4]

In Greek mythology, Silenus was a companion and tutor to the wine god Dionysus. He is typically older than the satyrs of the Dionysian retinue (thiasos), and sometimes considerably older, in which case he may be referred to as a Papposilenus. Silen and its plural sileni refer to the mythological figure as a type that is sometimes thought to be differentiated from a satyr by having the attributes of a horse rather than a goat, though usage of the two words is not consistent enough to permit a sharp distinction.

In Greek mythology, maenads were the female followers of Dionysus and the most significant members of the thiasus, the god's retinue. Their name, which comes from μαίνομαι, literally translates as 'raving ones'. Maenads were known as Bassarids, Bacchae, or Bacchantes in Roman mythology after the penchant of the equivalent Roman god, Bacchus, to wear a bassaris or fox skin.

In Ancient Greece a thyrsus or thyrsos was a wand or staff of giant fennel covered with ivy vines and leaves, sometimes wound with taeniae and topped with a pine cone, artichoke, fennel, or by a bunch of vine-leaves and grapes or ivy-leaves and berries, carried during Hellenic festivals and religious ceremonies. The thyrsus is typically associated with the Greek god Dionysus, and represents a symbol of prosperity, fertility, and hedonism similarly to Dionysus.

In the pottery of ancient Greece, a kylix is the most common type of cup in the period, usually associated with the drinking of wine. The cup often consists of a rounded base and a thin stem under a basin. The cup is accompanied by two handles on opposite sides.

In Ancient Greece, the symposium was a part of a banquet that took place after the meal, when drinking for pleasure was accompanied by music, dancing, recitals, or conversation. Literary works that describe or take place at a symposium include two Socratic dialogues, Plato's Symposium and Xenophon's Symposium, as well as a number of Greek poems, such as the elegies of Theognis of Megara. Symposia are depicted in Greek and Etruscan art, that shows similar scenes.

Exekias was an ancient Greek vase painter and potter who was active in Athens between roughly 545 BC and 530 BC. Exekias worked mainly in the black-figure technique, which involved the painting of scenes using a clay slip that fired to black, with details created through incision. Exekias is regarded by art historians as an artistic visionary whose masterful use of incision and psychologically sensitive compositions mark him as one of the greatest of all Attic vase painters. The Andokides painter and the Lysippides Painter are thought to have been students of Exekias.

The Kleophon Painter is the name given to an anonymous Athenian vase painter in the red-figure style who flourished in the mid-to-late 5th century BC. He is thus named because one of the works attributed to him bears an inscription in praise of a youth named "Kleophon". He appears to have been originally from the workshop of Polygnotos, and in turn to have taught the so-called Dinos Painter. Three vases suggest a collaboration with the Achilles Painter, while a number of black-figure works have also been attributed to him by some scholars.

The Borghese Vase is a monumental bell-shaped krater sculpted in Athens from Pentelic marble in the second half of the 1st century BC as a garden ornament for the Roman market; it is now in the Louvre Museum.

Lydos was an Attic vase painter in the black-figure style. Active between about 560 and 540 BC, he was the main representative of the "Lydos Group". His signature, ό Λυδός, ho Lydos, inscribed on two vases, is informative regarding the cultural background of the artist. Either he immigrated to Athens from the Lydian Empire of King Kroisos, or he was born in Athens as the son of Lydian parents. In any case, he learned his trade in Athens.

Psiax was an Attic vase painter of the transitional period between the black-figure and red-figure styles. His works date to circa 525 to 505 BC and comprise about 60 surviving vases, two of which bear his signature. Initially he was allocated the name "Menon Painter" by John Beazley. Only later was it realised that the artist was identical with the painters signing as "Psiax".

The pottery of ancient Greece has a long history and the form of Greek vase shapes has had a continuous evolution from Minoan pottery down to the Hellenistic period. As Gisela Richter puts it, the forms of these vases find their "happiest expression" in the 5th and 6th centuries BC, yet it has been possible to date vases thanks to the variation in a form’s shape over time, a fact particularly useful when dating unpainted or plain black-gloss ware.

The Pan Painter was an ancient Greek vase-painter of the Attic red-figure style, probably active c. 480 to 450 BC. John Beazley attributed over 150 vases to his hand in 1912:

Cunning composition; rapid motion; quick deft draughtsmanship; strong and peculiar stylisation; a deliberate archaism, retaining old forms, but refining, refreshing, and galvanizing them; nothing noble or majestic, but grace, humour, vivacity, originality, and dramatic force: these are the qualities which mark the Boston krater, and which characterize the anonymous artist who, for the sake of convenience, may be called the 'master of the Boston Pan-vase', or, more briefly, 'the Pan-master'.

The Painter of Nicosia Olpe was an ancient Greek vase painter, who was producing work around 575 BC to 475 BC, and these dates are concluded from the vases that were found and attributed to the specific painter. All of the pieces are black-figure, and this can also be determined by the dates. The majority of vases that he painted were larger pieces; this is not something that he had control over, but he did have control over the scenes on the vases.

Eye-cup is the term describing a specific cup type in ancient Greek pottery, distinguished by pairs of eyes painted on the external surface.

The Crouching Satyr Eye-Cup is a ceramic vessel located in gallery 215B in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Massachusetts, is an ancient Greek kylix dating to the Archaic Period. The cup, which was used within Ancient Greek symposiums as a form of entertainment amongst drunken revelers, was bought in London from an old collection, and eventually purchased by the MFA from Edward Perry Warren in March 1903.

Python was a Greek vase painter in the city of Poseidonia in Campania, Southern Italy, one of the major cities of Magna Graecia in the fourth Century BC. Together with his close collaborator and likely master Asteas, Python is one of only two vase painters from Southern Italy whose names have survived on extant works. It has even been suggested that the joint workshop of Asteas and Python in Paestum was a family business.

The hoplites were soldiers from Ancient Greece who were usually free citizens. They had a very uniform and distinct appearance; specifically they were armed with a spear (dory) in their right hand and a heavy round shield in their left.

The calyx krater by the artist called the "Painter of the Berlin Hydria" depicting an Amazonomachy is an ancient Greek painted vase in the red figure style, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. It is a krater, a bowl made for mixing wine and water, and specifically a calyx krater, where the bowl resembles the calyx of a flower. Vessels such as these were often used at a symposion, which was an elite party for drinking.

The kylix depicting athletic combats is a ceramic drinking cup made approximately in the late Archaic period, 490 B.C., in Attica. It is currently in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston as part of The Ancient World Collections. The artist, Onesimos, used red-figure technique for the decoration, which was invented in Athens around 530 B.C. and quickly became one of the leading modes of decoration Athenian potters used. Red-figure technique was favored because it allowed for a greater representation of garments, emotions and anatomy making it useful for artists, such as Onesimos, to use in painting athletic events.

Ancient Greek funerary vases are decorative grave markers made in ancient Greece that were designed to resemble liquid-holding vessels. These decorated vases were placed on grave sites as a mark of elite status. There are many types of funerary vases, such as amphorae, kraters, oinochoe, and kylix cups, among others. One famous example is the Dipylon amphora. Every-day vases were often not painted, but wealthy Greeks could afford luxuriously painted ones. Funerary vases on male graves might have themes of military prowess, or athletics. However, allusions to death in Greek tragedies was a popular motif. Famous centers of vase styles include Corinth, Lakonia, Ionia, South Italy, and Athens.