Related Research Articles

Botulism is a rare and potentially fatal illness caused by a toxin produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum. The disease begins with weakness, blurred vision, feeling tired, and trouble speaking. This may then be followed by weakness of the arms, chest muscles, and legs. Vomiting, swelling of the abdomen, and diarrhea may also occur. The disease does not usually affect consciousness or cause a fever.

Botulinum toxin, or botulinum neurotoxin, is a highly potent neurotoxic protein produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum and related species. It prevents the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine from axon endings at the neuromuscular junction, thus causing flaccid paralysis. The toxin causes the disease botulism. The toxin is also used commercially for medical and cosmetic purposes. Botulinum toxin is an acetylcholine release inhibitor and a neuromuscular blocking agent.

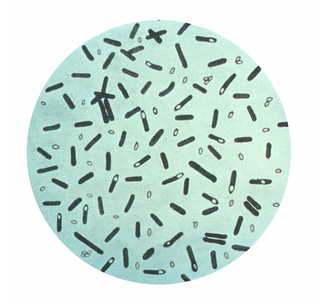

Clostridium botulinum is a gram-positive, rod-shaped, anaerobic, spore-forming, motile bacterium with the ability to produce botulinum toxin, which is a neurotoxin.

Tetanus toxin (TeNT) is an extremely potent neurotoxin produced by the vegetative cell of Clostridium tetani in anaerobic conditions, causing tetanus. It has no known function for clostridia in the soil environment where they are normally encountered. It is also called spasmogenic toxin, tentoxilysin, tetanospasmin, or tetanus neurotoxin. The LD50 of this toxin has been measured to be approximately 2.5–3 ng/kg, making it second only to the related botulinum toxin (LD50 2 ng/kg) as the deadliest toxin in the world. However, these tests are conducted solely on mice, which may react to the toxin differently from humans and other animals.

The pintail or northern pintail is a duck species with wide geographic distribution that breeds in the northern areas of Europe and across the Palearctic and North America. It is migratory and winters south of its breeding range to the equator. Unusually for a bird with such a large range, it has no geographical subspecies if the possibly conspecific duck Eaton's pintail is considered to be a separate species.

Avian influenza, also known as avian flu or bird flu, is a disease caused by the influenza A virus, which primarily affects birds but can sometimes affect mammals including humans. Wild aquatic birds are the primary host of the influenza A virus, which is enzootic in many bird populations.

Scavengers are animals that consume dead organisms that have died from causes other than predation or have been killed by other predators. While scavenging generally refers to carnivores feeding on carrion, it is also a herbivorous feeding behavior. Scavengers play an important role in the ecosystem by consuming dead animal and plant material. Decomposers and detritivores complete this process, by consuming the remains left by scavengers.

Dioctophyme renale, commonly referred to as the giant kidney worm, is a parasitic nematode (roundworm) whose mature form is found in the kidneys of mammals. D. renale is distributed worldwide, but is less common in Africa and Oceania. It affects fish-eating mammals, particularly mink and dogs. Human infestation is rare, but results in kidney destruction, usually of one kidney and hence not fatal. A 2019 review listed a total of 37 known human cases of dioctophymiasis in 10 countries with the highest number (22) in China. Upon diagnosis through tissue sampling, the only treatment is surgical excision.

Flaccid paralysis is a neurological condition characterized by weakness or paralysis and reduced muscle tone without other obvious cause. This abnormal condition may be caused by disease or by trauma affecting the nerves associated with the involved muscles. For example, if the somatic nerves to a skeletal muscle are severed, then the muscle will exhibit flaccid paralysis. When muscles enter this state, they become limp and cannot contract. This condition can become fatal if it affects the respiratory muscles, posing the threat of suffocation. It also occurs in the spinal shock stage in complete transection of the spinal cord occurring in injuries such as gunshot wounds.

A water bird, alternatively waterbird or aquatic bird, is a bird that lives on or around water. In some definitions, the term water bird is especially applied to birds in freshwater ecosystems, although others make no distinction from seabirds that inhabit marine environments. Some water birds are more terrestrial while others are more aquatic, and their adaptations will vary depending on their environment. These adaptations include webbed feet, beaks, and legs adapted to feed in the water, and the ability to dive from the surface or the air to catch prey in water.

Fowl cholera is also called avian cholera, avian pasteurellosis and avian hemorrhagic septicemia.

Histomoniasis is a commercially significant disease of poultry, particularly of chickens and turkeys, due to parasitic infection of a protozoan, Histomonas meleagridis. The protozoan is transmitted to the bird by the nematode parasite Heterakis gallinarum. H. meleagridis resides within the eggs of H. gallinarum, so birds ingest the parasites along with contaminated soil or food. Earthworms can also act as a paratenic host.

Animal lead poisoning is a veterinary condition and pathology caused by increased levels of the heavy metal lead in an animal's body.

Clostridium tertium is an anaerobic, motile, gram-positive bacterium. Although it can be considered an uncommon pathogen in humans, there has been substantial evidence of septic episodes in human beings. C. tertium is easily decolorized in Gram-stained smears and can be mistaken for a Gram-negative organism. However, C.tertium does not grow on selective media for Gram-negative organisms.

Patricia G. Parker is a North American evolutionary biologist who uses molecular techniques to assess social structures, particularly in avian populations. Her interests have shaped her research in disease transmission and population size, particularly in regard to bird conservation. She received her B.S. in Zoology in 1975 and her Ph.D. in Behavioral Ecology in 1984, both from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. From 1991 to 2000, Parker was an Assistant and Associate Professor in the Department of Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology at Ohio State University. From 2000 to 2022, she was the Des Lee Professor of Zoological Studies at the University of Missouri–St. Louis.

Eustrongylidosis is a parasitic disease that mainly affects wading birds worldwide; however, the parasite's complex, indirect lifecycle involves other species, such as aquatic worms and fish. Moreover, this disease is zoonotic, which means the parasite can transmit disease from animals to humans. Eustrongylidosis is named after the causative agent Eustrongylides, and typically occurs in eutrophicated waters where concentrations of nutrients and minerals are high enough to provide ideal conditions for the parasite to thrive and persist. Because eutrophication has become a common issue due to agricultural runoff and urban development, cases of eustrongylidosis are becoming prevalent and hard to control. Eustrongylidosis can be diagnosed before or after death by observing behavior and clinical signs, and performing fecal flotations and necropsies. Methods to control it include preventing eutrophication and providing hosts with uninfected food sources in aquaculture farms. Parasites are known to be indicators of environmental health and stability, so should be studied further to better understand the parasite's lifecycle and how it affects predator-prey interactions and improve conservation efforts.

Avian vacuolar myelinopathy (AVM) is a fatal neurological disease that affects various waterbirds and raptors. It is most common in the bald eagle and American coot, and it is known in the killdeer, bufflehead, northern shoveler, American wigeon, Canada goose, great horned owl, mallard, and ring-necked duck. Avian vacuolar myelinopathy is a newly discovered disease that was first identified in the field in 1994 when dead bald eagles were found near DeGray Lake in Arkansas in the United States. Since then, it has spread to four more states and infested multiple aquatic systems including 10 reservoirs. The cause of death is lesions on the brain and spinal cord. A neurotoxin called aetokthonotoxin produced by cyanobacteria causes the disease.

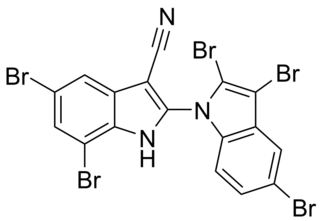

Aetokthonotoxin (AETX), colloquially known as eagle toxin, is a chemical compound that was identified in 2021 as the cyanobacterial neurotoxin causing vacuolar myelinopathy (VM) in eagles in North America. As the biosynthesis of aetokthonotoxin depends on the availability of bromide ions in freshwater systems and requires an interplay between the toxin-producing cyanobacterium Aetokthonos hydrillicola and the host plant it requires to live, it took more than 25 years to identify aetokthonotoxin as the VM-inducing toxin after the disease has first been diagnosed in bald eagles in 1994. The toxin cascades through the food-chain: Among other animals, it builds up in fish and waterfowl such as coots or ducks which feed on hydrilla colonized with the cyanobacterium. Aetokthonotoxin is transmitted to raptors, such as the bald eagle, as they prey on AETX poisoned animals. The total synthesis of AETX was achieved in 2021, the enzymatic functions of the 5 enzymes involved in AETX biosynthesis were described in 2022.

Baylisascaris schroederi is a species of roundworm in the family Ascarididae. It occurs in China and is a parasite of giant pandas. Many wild giant pandas are infected with this parasite.

Eric A. Johnson is a microbiologist and an academic. He is a retired Professor of Bacteriology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, serving from 1985 to 2020.

References

- 1 2 Kadlec, John (2002). "Avian Botulism in Great Salt Lake Marshes: Perspectives and Possible Mechanisms". Wildlife Society Bulletin. 30 (3): 983–989.

- ↑ LaFrancois, Brenda; Stephen C. Riley; David S. Blehert; Anne E. Ballmann (2011). "Links between type E botulism outbreaks, lake levels, and surface water temperatures in Lake Michigan, 1963–2008". Journal of Great Lakes Research. 37 (1): 86–91. Bibcode:2011JGLR...37...86L. doi:10.1016/j.jglr.2010.10.003.

- 1 2 3 Rocke, Tonie; Michael D. Samuel; Pamela K. Swift; Gregory S. Yarris (2000). "Efficacy of a Type C botulism vaccine in green-winged teal". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 36 (3): 489–493. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-36.3.489. PMID 10941734.

- ↑ Yule, Adam; Ian K. Barker; John W. Austin; Richard D. Moccia (2006). "Toxicity of Clostridium Botulinum Type E Neurotoxin to Great Lakes Fish: Implications for Avian Botulism". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 42 (3): 479–493. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-42.3.479 . hdl: 10214/24249 . PMID 17092878.

- 1 2 3 4 Soos, Catherine; Gary Wobeser (2006). "Identification of Primary Substrate in the Initiation of Avian Botulism Outbreaks". Journal of Wildlife Management. 70 (1): 43–53. doi:10.2193/0022-541x(2006)70[43:iopsit]2.0.co;2.

- 1 2 Takeda, Masato; Kentaro Tsukamoto; Tomoko Kohda; Miki Matsui; Masafumi Mukamoto; Shunji Kozaki (2005). "Characterization of the Nerotoxin produced by isolates associated with avian botulism". Avian Diseases. 49 (3): 376–381. doi:10.1637/7347-022305r1.1. PMID 16252491.

- 1 2 Work, Thierry; John L. Klavitter; Michelle H. Reynolds; David Blehert (2010). "Avian Botulism: A Case Study in Translocated Endangered Laysan Ducks (Anas Laysanensis) on Midway Atoll". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 46 (2): 499–506. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-46.2.499. PMID 20688642.

- ↑ Franciosa, G; L. Fenicia; C. Caldiani; P. Aureli (1996). "PCR for detection of Clostridium botulinum type C in avian and environmental samples". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 34 (4): 882–885. doi:10.1128/jcm.34.4.882-885.1996. PMC 228910 . PMID 8815101.