Under the English common law, an accomplice is a person who actively participates in the commission of a crime, even if they take no part in the actual criminal offense. For example, in a bank robbery, the person who points the gun at the teller and demands the money is guilty of armed robbery. Anyone else directly involved in the commission of the crime, such as the lookout or the getaway car driver, is an accomplice, even if in the absence of an underlying offense keeping a lookout or driving a car would not be an offense.

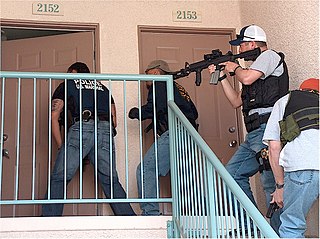

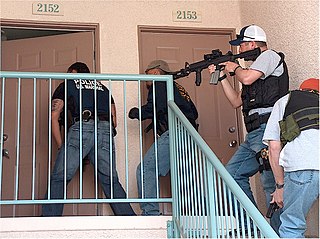

Knock-and-announce, in United States law criminal procedure, is an ancient common law principle, incorporated into the Fourth Amendment, which requires law enforcement officers to announce their presence and provide residents with an opportunity to open the door prior to a search.

Dennis Jacobs is a senior United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution creates several constitutional rights, limiting governmental powers regarding both criminal procedure and civil matters. It was ratified, along with nine other articles, in 1791 as part of the Bill of Rights. The Fifth Amendment applies to every level of the government, including the federal, state, and local levels, in regard to any "person". The Supreme Court furthered the protections of this amendment through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In United States law, a federal enclave is a parcel of federal property within a state that is under the "Special Maritime and Territorial Jurisdiction of the United States". In 1960, the year of the latest comprehensive inquiry, 7% of federal property had enclave status. Of the land with federal enclave status, 57% was under "concurrent" state jurisdiction. The remaining 43%, on which some state laws do not apply, was scattered almost at random throughout the United States. In 1960, there were about 5,000 enclaves, with about one million people living on them. While a comprehensive inquiry has not been performed since 1960, these statistics are likely much lower today, since many federal enclaves were military bases that have been closed and transferred out of federal ownership.

United States v. Weitzenhoff, 35 F.3d 1275 is a legal opinion from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals that addresses the confusing mens rea requirement of a federal environmental law that imposed criminal sanctions on certain polluters. The main significance of the court's opinion was that it interpreted the word "knowingly" in the statute to mean a general awareness of the wrongfulness of one's actions or the likelihood of illegality, rather than an actual knowledge of the statute being violated. Circuit Court Judge Betty Binns Fletcher authored the majority's legal opinion in this case.

Tax protesters in the United States advance a number of constitutional arguments asserting that the imposition, assessment and collection of the federal income tax violates the United States Constitution. These kinds of arguments, though related to, are distinguished from statutory and administrative arguments, which presuppose the constitutionality of the income tax, as well as from general conspiracy arguments, which are based upon the proposition that the three branches of the federal government are involved together in a deliberate, on-going campaign of deception for the purpose of defrauding individuals or entities of their wealth or profits. Although constitutional challenges to U.S. tax laws are frequently directed towards the validity and effect of the Sixteenth Amendment, assertions that the income tax violates various other provisions of the Constitution have been made as well.

A tax protester is someone who refuses to pay a tax claiming that the tax laws are unconstitutional or otherwise invalid. Tax protesters are different from tax resisters, who refuse to pay taxes as a protest against a government or its policies, or a moral opposition to taxation in general, not out of a belief that the tax law itself is invalid. The United States has a large and organized culture of people who espouse such theories. Tax protesters also exist in other countries.

United States v. Lara, 541 U.S. 193 (2004), was a United States Supreme Court landmark case which held that both the United States and a Native American (Indian) tribe could prosecute an Indian for the same acts that constituted crimes in both jurisdictions. The Court held that the United States and the tribe were separate sovereigns; therefore, separate tribal and federal prosecutions did not violate the Double Jeopardy Clause.

United States v. Peoni, 100 F.2d 401, was a criminal case that the prosecution must establish that the mental state of an accomplice to a crime include a purpose to aid or encourage, and thereby facilitate the criminal conduct of the principal. This showing of purpose is contrasted with showing knowledge that the principal would commit the crime, which does not necessarily imply that the purpose of acting to aid or abet was to facilitate the criminal act of the principal.

The Insanity Defense Reform Act of 1984 (IDRA) was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan on October 12, 1984, amending the United States federal laws governing defendants with mental diseases or defects to make it significantly more difficult to obtain a verdict of not guilty only by reason of insanity.

The Assistance of Counsel Clause of the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution provides: "In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right...to have the Assistance of Counsel for his defence."

Several statutes, mostly codified in Title 18 of the United States Code, provide for federal prosecution of public corruption in the United States. Federal prosecutions of public corruption under the Hobbs Act, the mail and wire fraud statutes, including the honest services fraud provision, the Travel Act, and the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) began in the 1970s. "Although none of these statutes was enacted in order to prosecute official corruption, each has been interpreted to provide a means to do so." The federal official bribery and gratuity statute, 18 U.S.C. § 201, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) 15 U.S.C. § 78dd, and the federal program bribery statute, 18 U.S.C. § 666 directly address public corruption.

The Assimilative Crimes Act, 18 U.S.C. § 13, makes state law applicable to conduct occurring on lands reserved or acquired by the Federal government as provided in 18 U.S.C. § 7(3), when the act or omission is not made punishable by an enactment of Congress.

Walker Process Equipment, Inc. v. Food Machinery & Chemical Corp., 382 U.S. 172 (1965), was a 1965 decision of the United States Supreme Court that held, for the first time, that enforcement of a fraudulently procured patent violated the antitrust laws and provided a basis for a claim of treble damages if it caused a substantial anticompetitive effect.

United States v. Pohlot, 827 F.2d 889, is a criminal case that summarized diverse uses of the expression "diminished capacity".

United States v. Brawner, 471 F.2d 969, is decision by the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in which the Court held that a person is not responsible for criminal conduct if at the time of such conduct as a result of mental disease or defect, he lacked substantial capacity either to appreciate the criminality of his conduct or conform his conduct to the requirements of the law.

United States v. Giovanetti, 919 F.2d 1223, is a criminal case that interpreted the jury instruction known as the ostrich instruction, that willful ignorance counted as knowledge where required for a guilty mind in complicity to commit a crime. The court held that willful ignorance required a positive act to avoid knowledge, otherwise it reduces the mens rea requirement of proving "knowledge" to merely proving "negligence".

Julius Ness "Jay" Richardson is an American judge and lawyer who serves as a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. He was formerly an Assistant United States Attorney for the District of South Carolina.