Don Miguel Gregorio Antonio Ignacio Hidalgo y Costilla Gallaga Mandarte y Villaseñor, commonly known as Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla or simply Miguel Hidalgo, was a Catholic priest, leader of the Mexican War of Independence, and is recognized as the Father of the Nation.

The Cry of Dolores occurred in Dolores, Mexico, on 16 September 1810, when Roman Catholic priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla rang his church bell and gave the call to arms that triggered the Mexican War of Independence. The Cry of Dolores is most commonly known by the locals as "El Grito de Independencia".

José María Teclo Morelos Pérez y Pavón was a Mexican Catholic priest, statesman and military leader who led the Mexican War of Independence movement, assuming its leadership after the execution of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla in 1811.

Guanajuato, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Guanajuato, is one of the 32 states that make up the Federal Entities of Mexico. It is divided into 46 municipalities and its capital city is Guanajuato.

The Mexican War of Independence was an armed conflict and political process resulting in Mexico's independence from the Spanish Empire. It was not a single, coherent event, but local and regional struggles that occurred within the same period, and can be considered a revolutionary civil war. It culminated with the drafting of the Declaration of Independence of the Mexican Empire in Mexico City on September 28, 1821, following the collapse of royal government and the military triumph of forces for independence.

Ignacio José de Allende y Unzaga, commonly known as Ignacio Allende, was a captain of the Spanish Army in New Spain who came to sympathize with the Mexican independence movement. He attended the secret meetings organized by Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez, where the possibility of an independent Mexico was discussed. He fought along with Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla in the first stage of the struggle, eventually succeeding him in leadership of the rebellion. Allende was captured by Spanish colonial authorities while he was in Coahuila and executed for treason in Chihuahua.

Juan Aldama was a Mexican revolutionary rebel soldier during the Mexican War of Independence in 1810.

José Mariano Jiménez was a Mexican engineer and rebel officer active at the beginning of the Mexican War of Independence.

The Bajío is a cultural and geographical region within the central Mexican plateau which roughly spans from northwest of Mexico City to the main silver mines in the northern-central part of the country. This includes the states of Querétaro, Guanajuato, parts of Jalisco, Aguascalientes and parts of Zacatecas, San Luis Potosí and Michoacán.

Francisco Javier Venegas de Saavedra y Ramínez de Arenzana, 1st Marquess of Reunión and New Spain, KOC was a Spanish general in the Spanish War of Independence and later viceroy of New Spain from September 14, 1810, to March 4, 1813, during the first phase of the Mexican War of Independence.

Félix María Calleja del Rey y de la Gándara, primer conde de Calderón was a Spanish military officer and viceroy of New Spain from March 4, 1813, to September 20, 1816, during Mexico's War of Independence. For his service in New Spain, Calleja was awarded with the title Count of Calderon.

Jose Mariano de Abasolo (1783–1816) was a Mexican revolutionist, born at Dolores, Guanajuato. He participated in the revolution started by Miguel Hidalgo.

The Battle of Calderón Bridge was a decisive battle in the Mexican War of Independence. It was fought in January 1811 on the banks of the Calderón River 60 km (37 mi) east of Guadalajara in present-day Zapotlanejo, Jalisco.

La Marquesa National Park, with the official name Parque Nacional Insurgente Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, is a National park in the State of Mexico, in central Mexico.

Events in the year 1810 in Mexico.

Francisco Ignacio de Elizondo Villarreal,, was a royalist military officer during the Mexican war of independence against Spain. He is mostly known for his capture of insurgent leaders Miguel Hidalgo, Ignacio Allende, José Mariano Jiménez, and Juan Aldama at the Wells of Baján, Coahuila in 1811. Initially a supporter of Mexican independence who converted to the royalist cause, Elizondo is sometimes compared to the American Benedict Arnold. In 1813, after a successful campaign against rebel armies he was assassinated by one of his junior officers.

The siege of Cuautla was a battle of the War of Mexican Independence that occurred from 19 February through 2 May 1812 at Cuautla, Morelos. The Spanish royalist forces loyal to the Spanish, commanded by Félix María Calleja, besieged the town of Cuautla and its Mexican rebel defenders fighting for independence from the Spanish Empire. The rebels were commanded by José María Morelos y Pavón, Hermenegildo Galeana, and Mariano Matamoros. The battle results are disputed, but it is generally agreed that the battle resulted more favorably for the Spanish whose siege was ultimately successful with the Mexican withdrawal on 2 May 1812.

The following is a partial timeline (1810–1812) of the Mexican War of Independence (1810–1821), its antecedents and its aftermath. The war pitted the royalists, supporting the continued adherence of Mexico to Spain, versus the insurgents advocating Mexican independence from Spain. After a struggle of more than 10 years the insurgents prevailed.

Wells of Baján are water wells located between Saltillo and Monclova in the northern Mexican state of Coahuila. The small community near the wells is called Acatita de Baján. In the first phase of the Mexican War of Independence, revolutionary leaders Miguel Hidalgo, Ignacio Allende, José Mariano Jiménez, and Juan Aldama, plus nearly 900 men in the rebel army were captured here on March 21, 1811, by 150 soldiers commanded by Ignacio Elizondo. Elizondo pretended to be a supporter of the struggle to overthrow Spanish rule, lured the rebels into a trap, and captured them with little resistance. The four leaders and many of their followers were tried and executed.

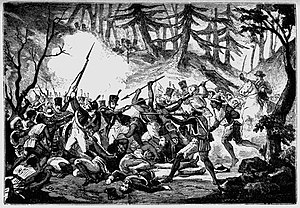

The Capture of Alhóndiga de Granaditas was a military action carried out in Guanajuato, viceroyalty of New Spain, on September 28, 1810, between the royalist soldiers of the province and the insurgents commanded by Miguel Hidalgo and Ignacio Allende. The fear unleashed in the social circles of the provincial capital made the intendant, Juan Antonio Riaño, ask the population to barrack in the Alhóndiga de Granaditas, a granary built in 1800, and in whose construction Miguel Hidalgo had participated as an advisor to his old friend Riaño. After several hours of combat, Riaño was killed and the Spaniards who had taken refuge there wished to surrender. The military in the viceroy's service continued the fight, until the insurgents managed to enter and then massacred not only the few guards that defended it, but also the numerous families of civilians who had taken refuge there. Many historians consider this confrontation more like a mutiny or massacre of civilians than a battle, since there were no conditions of military equality between the two sides.