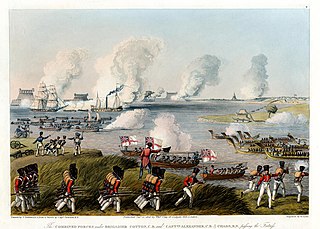

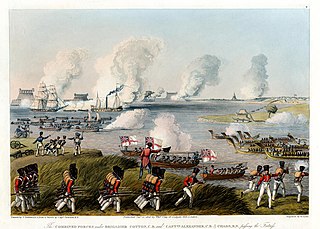

The First Anglo-Burmese War, also known as the First Burma War, was the first of three wars fought between the British and Burmese empires in the 19th century. The war, which began primarily over the control of what is now Northeastern India, ended in a decisive British victory, giving the British total control of Assam, Manipur, Cachar and Jaintia as well as Arakan Province and Tenasserim. The Burmese submitted to a British demand to pay an indemnity of one million pounds sterling, and signed a commercial treaty.

The Battle of the Admin Box took place on the southern front of the Burma campaign from 5 to 23 February 1944, in the South-East Asian Theatre of World War II.

The Battle of Danubyu was a battle between the British Empire and the Konbaung Dynasty as part of the First Anglo-Burmese War.

The battle of Prome was a land-based battle between the Kingdom of Burma and the British Empire that took place near the city of Prome, modern day Pyay, in 1825 as part of the First Anglo-Burmese War. It was the last-ditch effort by the Burmese to drive out the British from Lower Burma. The poorly equipped Burmese army despite the advantage in numbers suffered a defeat. The British army's subsequent march toward north threatened Ava, which led to peace negotiation by the Kingdom of Burma.

Myawaddy Mingyi U Sa was a Konbaung-era Burmese poet, composer, playwright, general and statesman. In a royal service career that spanned over six decades, the Lord of Myawaddy served under four kings in various capacities, and was a longtime secretary to King Bagyidaw. Multi-talented Sa is best remembered for his innovative contributions to classical Burmese music and drama, as well as for his brilliant military service.

The Rajput Regiment is one of the oldest infantry regiments of the Indian Army, tracing its origin back to 1778 with the raising of the 24th Regiment of Bengal Native Infantry. The 1st battalion of the regiment was formed in 1798.

Bagyidaw was the seventh king of the Konbaung dynasty of Burma from 1819 until his abdication in 1837. Prince of Sagaing, as he was commonly known in his day, was selected as crown prince by his grandfather King Bodawpaya in 1808, and became king in 1819 after Bodawpaya's death. Bagyidaw moved the capital from Amarapura back to Ava in 1823.

General Maha Bandula was commander-in-chief of the Royal Burmese Armed Forces from 1821 until his death in 1825 in the First Anglo-Burmese War. Bandula was a key figure in the Konbaung dynasty's policy of expansionism in Manipur and Assam that ultimately resulted in the war and the beginning of the downfall of the dynasty. Nonetheless, the general, who died in action, is celebrated as a national hero by the Burmese for his resistance to the British. Today, some of the most prominent places in the country are named after him.

The 26th Indian Infantry Division, was an infantry division of the Indian Army during World War II. It fought in the Burma Campaign.

The Maha Bandula Park or Maha Bandula Garden is a public park, located in downtown Yangon, Burma. The park is bounded by Maha Bandula Garden Street in the east, Sule Pagoda Road in the west, Konthe Road in the south and Maha Bandula Road in the north, and is surrounded by some of the important buildings in the area such as the Sule Pagoda, the Yangon City Hall and the High Court. The park is named after General Maha Bandula who fought against the British in the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826).

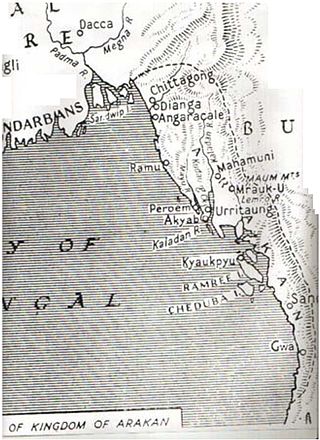

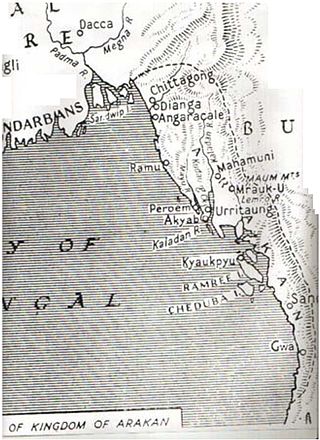

The Kingdom of Mrauk-U was a kingdom that existed on the Arakan littoral from 1429 to 1785. Based in the capital Mrauk-U, near the eastern coast of the Bay of Bengal, the kingdom ruled over what is now Rakhine State, Myanmar and southern part of Chittagong Division, Bangladesh. Though started out as a protectorate of the Bengal Sultanate from 1429 to 1531, Mrauk-U went on to conquer Chittagong with the help of the Portuguese. It twice fended off the Toungoo Burma's attempts to conquer the kingdom in 1546–1547, and 1580–1581. At its height of power, it briefly controlled the Bay of Bengal coastline from the Sundarbans to the Gulf of Martaban from 1599 to 1603. In 1666, it lost control of Chittagong after a war with the Mughal Empire. Its reign continued until 1785, when it was conquered by the Konbaung dynasty of Burma.

The military history of Myanmar (Burma) spans over a millennium, and is one of the main factors that have shaped the history of the country, and to a certain degree, the history of Southeast Asia. At various times in history, successive Burmese kingdoms were also involved in warfare against their neighbouring states in the surrounding regions of modern Burmese borders—from Bengal, Manipur and Assam in the west, to Yunnan (the southern China) in the northeast, to Laos and Siam in the east and southeast.

Min Bin was a king of Arakan from 1531 to 1554, "whose reign witnessed the country's emergence as a major power". Aided by Portuguese mercenaries and their firearms, his powerful navy and army pushed the boundaries of the kingdom deep into Bengal, where coins bearing his name and styling him sultan were struck, and even interfered in the affairs of mainland Burma.

The city of Chattogram (Chittagong) is traditionally centred around its seaport which has existed since the 4th century BCE. One of the world's oldest ports with a functional natural harbor for centuries, Chittagong appeared on ancient Greek and Roman maps, including on Ptolemy's world map. Chittagong port is the oldest and largest natural seaport and the busiest port of Bay of Bengal. It was located on the southern branch of the Silk Road. The city was home to the ancient independent Buddhist kingdoms of Bengal like Samatata and Harikela. It later fell under of the rule of the Gupta Empire, the Gauda Kingdom, the Pala Empire, the Sena Dynasty, the Deva Dynasty and the Arakanese kingdom of Waithali. Arab Muslims traded with the port from as early as the 9th century. Historian Lama Taranath is of the view that the Buddhist king Gopichandra had his capital at Chittagong in the 10th century. According to Tibetan tradition, this century marked the birth of Tantric Buddhism in the region. The region has been explored by numerous historic travellers, most notably Ibn Battuta of Morocco who visited in the 14th century. During this time, the region was conquered and incorporated into the independent Sonargaon Sultanate by Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah in 1340 AD. Sultan Ghiyasuddin Azam Shah constructed a highway from Chittagong to Chandpur and ordered the construction of many lavish mosques and tombs. After the defeat of the Sultan of Bengal Ghiyasuddin Mahmud Shah in the hands of Sher Shah Suri in 1538, the Arakanese Kingdom of Mrauk U managed to regain Chittagong. From this time onward, until its conquest by the Mughal Empire, the region was under the control of the Portuguese and the Magh pirates for 128 years.

Min Khayi was the second king of the Mrauk-U Kingdom from 1433 to 1459.

Min Razagyi, also known as Salim Shah, was king of Arakan from 1593 to 1612. His early reign marked the continued ascent of the coastal kingdom, which reached full flight in 1599 by defeating its nemesis Toungoo Dynasty, and temporarily controlling the Bay of Bengal coastline from the Sundarbans to the Gulf of Martaban until 1603. But the second half of his reign saw the limits of his power: he lost the Lower Burmese coastline in 1603 and a large part of Bengal coastline in 1609 due to insurrections by Portuguese mercenaries. He died in 1612 while struggling to deal with Portuguese raids on the Arakan coast itself.

The Toungoo–Mrauk-U War was a military conflict that took place in Arakan from 1545 to 1547 between the Toungoo Dynasty and the Kingdom of Mrauk U. The western kingdom successfully fended off the Toungoo invasions, and kept its independence. The war had a deterrence effect: Mrauk U would not see another Toungoo invasion until 1580.

Arakan is the historical geographical name of Rakhine State, Myanmar. The region was called Arakan for centuries until the Burmese military junta changed its name in 1989. The people of the region were known as Arakanese.

Arakan Division was an administrative division of the British Empire, covering modern-day Rakhine State, Myanmar, which was the historical region of Arakan. It bordered the Bengal Presidency of British India to the north. The Bay of Bengal was located on its western coastline. Arakan Division had a multiethnic population. It was a leading rice exporter.

The restoration of Min Saw Mon was a military campaign led by the Bengal Sultanate to help Min Saw Mon regain control of his Launggyet Dynasty. The campaign was successful. Min Saw Mon was restored to the Launggyet throne, and northern Arakan became a vassal state of the Bengal Sultanate.