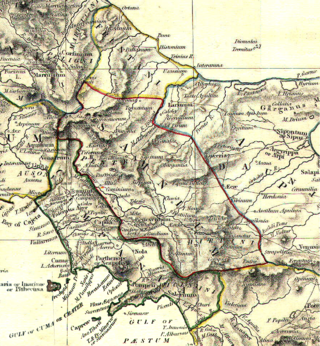

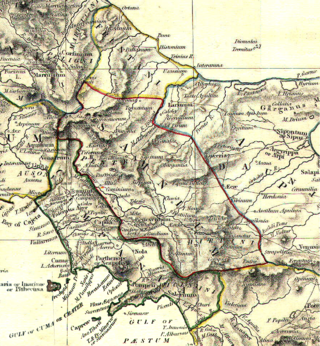

The Osci were an Italic people of Campania and Latium adiectum before and during Roman times. They spoke the Oscan language, also spoken by the Samnites of Southern Italy. Although the language of the Samnites was called Oscan, the Samnites were never referred to as Osci, nor were the Osci called Samnites.

The First, Second, and Third Samnite Wars were fought between the Roman Republic and the Samnites, who lived on a stretch of the Apennine Mountains south of Rome and north of the Lucanian tribe.

Marcus Valerius Corvus, also sometimes known as Corvinus, was a military commander and politician who served in the early-to-middle period of the Roman Republic. During his career he was elected consul six times, beginning at the age of twenty-three. He was appointed dictator twice and led the armies of the Republic in the First Samnite War. He occupied the curule chair twenty-one times throughout his career. According to legend, he lived to the age of one hundred.

The Battle of Mount Gaurus, 343 BC, was the first battle of the First Samnite War and also the first battle fought between the Roman Republic and the Samnites. The battle is described by the Roman historian Livy as part of Book Seven of his history of Rome, Ab Urbe Condita Libri, where he narrates how the Roman consul Marcus Valerius Corvus won a hard-fought battle against the Samnites at Mount Gaurus, near Cumae, in Campania. Modern historians however believe that most, if not all, of the detail in Livy's description has been invented by him or his sources.

Lucius Papirius Cursor was a celebrated politician and general of the early Roman Republic, who was five times consul, three times magister equitum, and twice dictator. He was the most important Roman commander during the Second Samnite War, during which he received three triumphs.

The Battle of Vesuvius was the first recorded battle of the Latin War. The battle was fought near Mount Vesuvius in 340 BC between the Romans, with their allies the Samnites, against a coalition of several peoples: Latins, Campanians, Volsci, Sidicini, and Aurunci. The surviving sources on the battle, however, focus almost solely on the Romans and the Latins.

Suessula was an ancient city of Campania, southern Italy, situated in the interior of the peninsula, near the frontier with Samnium, between Capua and Nola, and about 7 km northeast of Acerrae, Suessula is now a vanished city and the archeological site belongs to the city of Acerra, and not to San Felice a Cancello as reported in some sources.

The (Second) Latin War of 340–338 BC was a conflict between the Roman Republic and its neighbors, the Latin peoples of ancient Italy. It ended in the dissolution of the Latin League and incorporation of its territory into the Roman sphere of influence, with the Latins gaining partial rights and varying levels of citizenship.

The military campaigns of the Samnite Wars were an important stage in Roman expansion in the Italian Peninsula.

The Roman–Etruscan Wars, also known as the Etruscan Wars or the Etruscan–Roman Wars, were a series of wars fought between ancient Rome and the Etruscans. Information about many of the wars is limited, particularly those in the early parts of Rome's history, and in large part is known from ancient texts alone. The conquest of Etruria was completed in 265–264 BC.

Gaius Junius Bubulcus Brutus was a Roman general and statesman, he was elected consul of the Roman Republic thrice, he was also appointed dictator or magister equitum thrice, and censor in 307 BC. In 311, he made a vow to the goddess Salus that he went on to fulfill, becoming the first plebeian to build a temple. The temple was one of the first dedicated to an abstract deity, and Junius was one of the first generals to vow a temple and then oversee its establishment through the construction and dedication process.

The Roman–Latin wars were a series of wars fought between ancient Rome and the Latins, from the earliest stages of the history of Rome until the final subjugation of the Latins to Rome in the aftermath of the Latin War.

The Roman–Volscian wars were a series of wars fought between the Roman Republic and the Volsci, an ancient Italic people. Volscian migration into southern Latium led to conflict with that region's old inhabitants, the Latins under leadership of Rome, the region's dominant city-state. By the late 5th century BC, the Volsci were increasingly on the defensive and by the end of the Samnite Wars had been incorporated into the Roman Republic. The ancient historians devoted considerable space to Volscian wars in their accounts of the early Roman Republic, but the historical accuracy of much of this material has been questioned by modern historians.

The Roman conquest of the Hernici, an ancient Italic people, took place during the 4th century BC. For most of the 5th century BC, the Roman Republic had been allied with the other Latin states and the Hernici to successfully fend off the Aequi and the Volsci. In the early 4th century BC, this alliance fell apart. A war fought between Rome and the Hernici in the years 366–358 BC ended in Roman victory and the submission of the Hernici. Rome also defeated a rebellion by some Hernician cities in 307–306 BC. The rebellious Hernici were incorporated directly into the Roman Republic, while those who had stayed loyal retained their autonomy and nominal independence. In the course of the following century, the Hernici became indistinguishable from their Latin and Roman neighbours and disappeared as a separate people.

Gnaeus Fulvius Maximus Centumalus was a military commander and politician from the middle period of the Roman Republic, who became consul in 298 BC. He fought in the final wars against the Etruscans and later led armies in the Third Samnite War. He was appointed dictator in 263 BC with responsibility for overseeing the start of the Roman ship building effort in the First Punic War.

The Battle of Saticula, 343 BC, was the second of three battles described by the Roman historian Livy, in Book Seven of his history of Rome, Ab Urbe Condita, as taking place in the first year of the First Samnite War. According to Livy's extensive description, the Roman commander, the consul Aulus Cornelius Cossus was marching from Saticula when he was almost trapped by a Samnite army in a mountain pass. His army was only saved because one of his military tribunes, Publius Decius Mus, led a small group of men to seize a hilltop, distracting the Samnites and allowing the consul to escape. During the night Decius and his men were themselves able to escape. The next day the reunited Romans attacked the Samnites and completely routed them. Several other ancient authors also mention Decius' heroic acts. Modern historians are however sceptical of the historical accuracy of Livy's account, and have in particular noted the similarities with how a military tribune is said to have saved Roman army in 258 BC during the First Punic War.

Several ancient authors have written descriptions of a Roman army mutiny in 342 BC. According to the most well-known version, the mutiny originated in a group of Roman garrison soldiers wintering in Campania to protect the cities there against the Samnites. Subverted by the luxurious living of the Campanians, these soldiers conspired to take over their host cities. When the conspiracy was discovered, the conspirators formed a rebel army and marched against Rome. They were met by an army commanded by Marcus Valerius Corvus who had been nominated dictator to solve the crisis. Rather than do battle, Corvus managed to end the mutiny by peaceful means. All the mutineers received amnesty for their part in the rebellion and a series of laws were passed to address their political grievances.

The Sidicini were one of the Italic peoples of ancient Italy. Their territory extended northward from their capital, Teanum Sidicinum, along the valley of the Liri river up to Fregellae, covering around 3,000 square kilometres in total. They were neighbors of the Samnites and Campanians, and allies of the Ausones and Aurunci. Their language was Oscan.

Aulus Cornelius Cossus Arvina was a Roman statesman and general who served as both consul and Magister Equitum twice, and Dictator in 322 BC.

Gaius Sulpicius Longus was an accomplished general and statesman of the Roman Republic who served as Consul thrice and dictator once during his career, triumphing once over the Samnites and achieving great political success.