Related Research Articles

The Kiryat Shmona massacre was an attack by three members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - General Command on civilians in Kiryat Shmona, Israel during the Jewish holiday of Passover on 11 April 1974. Eighteen people were killed, 8 of them children, and 16 people were wounded.

Emmanuel Wilmer was a Haitian criminal, rebel, and anarchist killed in a United Nations armed assault on Cité Soleil that killed dozens of people. The assault was led by Brazilian general Augusto Heleno and was carried out by COMANF on July 6, 2005. Cité Soleil, the location where the assault occurred, was largely governed by Aristide-backed gangs affiliated with Fanmi Lavalas who monitored visitors via two roads that accessed the slum.

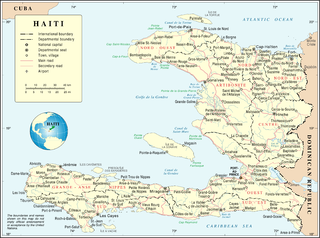

Cité Soleil is an extremely impoverished and densely populated commune located in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area in Haiti. Cité Soleil originally developed as a shanty town and grew to an estimated 200,000 to 400,000 residents, the majority of whom live in extreme poverty. The area is generally regarded as one of the poorest and most dangerous areas of the Western Hemisphere and it is one of the biggest slums in the Northern Hemisphere. The area has virtually no sewers and has a poorly maintained open canal system that serves as its sewage system, few formal businesses but many local commercial activities and enterprises, sporadic but largely unpaid for electricity, a few hospitals, and two government schools, Lycée Nationale de Cité Soleil, and École Nationale de Cité Soleil. For several years until 2007, the area was ruled by a number of gangs, each controlling their own sectors. But government control was reestablished after a series of operations in early 2007 by the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) with the participation of the local population.

Bel Air is a neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, Haiti. It is a slum area of the city and suffers from poverty. Crime is widespread, and kidnappings and killings have created panic among the local population. The neighborhood is also noted for housing a community of artists and craftsmen who produce inspired by Haitian Vodou, such as flags.

On 13 November 2018, a massacre began within the La Saline slums of Port-au-Prince, Haiti. According to reports, at least 71 civilians were killed over a 24-hour period. It is alleged that the killings were either due to local gang wars or the actions of Haitian officials attempting to quell anti-corruption protests.

The current political, economic, and social crisis began with protests in cities throughout Haiti on 7 July 2018 in response to increased fuel prices. These protests gradually evolved into demands for the resignation of the president, Jovenel Moïse. Led by opposition politician Jean-Charles Moïse, protesters demanded a transitional government, provision of social programs, and the prosecution of corrupt officials. From 2019 to 2021, massive protests called for the Jovenel Moïse government to resign. Moïse had come to power in the 2016 presidential election, which had voter turnout of only 21%. Previously, the 2015 elections had been annulled due to fraud. On 7 February 2021, supporters of the opposition allegedly attempted a coup d'état, leading to 23 arrests, as well as clashes between protestors and police.

Events in the year 2021 in Haiti.

Jimmy Chérizier, nicknamed Barbecue, is a Haitian gang leader, former police officer, and warlord who is the head of the Revolutionary Forces of the G9 Family and Allies, abbreviated as "G9" or "FRG9", a federation of over a dozen Haitian gangs based in Port-au-Prince. Known for often making public appearances in military camouflage and a beret, he calls himself the leader of an "armed revolution". Considered the most powerful warlord in Haiti, he is currently believed to be one of the country's most powerful figures.

In July 2022, an outbreak of gang violence occurred in the Haitian capital of Port-au-Prince, leaving 89 people dead and over 74 injured.

Events in the year 2022 in Haiti.

The socioeconomic and political crisis in Haiti has been marked by rising energy prices due to the 2022 global energy crisis, as well as protests, and civil unrest against the government of Haiti, armed gang violence, an outbreak of cholera, shortages of fuel and clean drinking water, as well as widespread acute hunger. It is a continuation of instability and protests that began in 2018.

Since 2020, Haiti's capital Port-au-Prince has been the site of an ongoing gang war. The government of Haiti and Haitian security forces have struggled to maintain their control of Port-au-Prince amid this conflict, with gangs reportedly controlling up to 90% of the city by 2023. In response to the escalating gang fighting, an armed vigilante movement, known as bwa kale, also emerged, with the purpose of fighting the gangs. On 2 October 2023, United Nations Security Council Resolution 2699 was approved, authorizing a Kenya-led "multinational security support mission" to Haiti. Until 2024, the war was between two major groups and their allies: the Revolutionary Forces of the G9 Family and Allies and the G-Pep. However, in February 2024 the two rival gangs formed a coalition opposing the government and the UN mission.

Between April 24 and May 6, 2022, clashes broke out between the 400 Mawozo gang and the Chen Mechan gang in Plaine du Cul-de-Sac, Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Nearly 200 people were killed, many of whom were civilians.

Events in the year 2024 in Haiti.

Vitel'Homme Innocent is a Haitian gang leader who was added to the FBI Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list on November 15, 2023, for his role in the 2021 Haitian missionary kidnappings. A reward of up to 2 million dollars is offered for information leading to his capture.

Between January 10 and 26, 2023, eighteen police officers were killed by Gan Grif, a gang operating in Port-au-Prince. The killings sparked riots in Port-au-Prince by Haitian police officers and police-affiliated gang Fantom 509, along with international condemnation.

Amid the unrest in Haiti since 2018, armed gangs stormed Haiti's two largest prisons in March 2024, resulting in more than 4,700 inmates escaping. The gangs demanded that prime minister Ariel Henry resign, attacking and closing Toussaint Louverture International Airport and preventing Henry from entering the country. The Haitian government declared a 72-hour state of emergency and a nighttime curfew in Ouest Department in an attempt to curb the violence and chaos. On 12 March 2024, Henry indicated his intention to resign as prime minister in response to the deteriorating security situation.

The Revolutionary Forces of the G9 Family and Allies is a federation of 12 gangs led by former Haitian police officer Jimmy "Barbecue" Chérizier, notorious for extrajudicial massacres. The G9, along with other affiliated gangs, controls over 80% of the capital Port-au-Prince.

Ernst Julme, known as Ti Greg, was a Haitian gang leader. He was reportedly the head of the Delmas 95 gang.

References

- ↑ "Gangs of Haiti: Expansion, power, and an escalating crisis" (PDF). Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. October 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 "Massacres in Bel Air and Cite Soleil Under the Indifferent Gaze of State Authorities" (PDF). National Human Rights Defense Network. May 20, 2021. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ↑ Chéry, Onz (2020-09-14). "Haiti PM: Helping during Bel Air massacre could have hurt more people". The Haitian Times. Retrieved 2023-08-28.

- ↑ Chéry, Onz (2020-09-10). "Haitian police drive armed bandits out of Bel Air". The Haitian Times. Retrieved 2023-08-28.

- ↑ Chéry, Onz (2020-10-06). "Bandits set houses on fire again in Bel Air". The Haitian Times. Retrieved 2023-08-28.

- ↑ Chéry, Onz (2020-10-19). "G9 members exchange shots with rival gang in Bel Air". The Haitian Times. Retrieved 2023-08-28.

- 1 2 3 Chéry, Onz (2021-04-02). "Battle for Bel Air Turns Fatal as Residents Resist Gang Takeover". The Haitian Times. Retrieved 2023-08-28.

- ↑ Charles, Jacqueline (April 2, 2021). "Gang attack in Haiti neighborhood left bodies, homes charred". Miami Herald. Retrieved August 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Haiti - FLASH : Attack in Bel Air, all the details and assessment (investigation) - HaitiLibre.com : Haiti news 7/7". www.haitilibre.com. Retrieved 2023-08-28.

- ↑ "Haiti - FLASH : Violent armed clashes, burned houses, of wounded and dead in Bel-Air - HaitiLibre.com : Haiti news 7/7". www.haitilibre.com. Retrieved 2023-08-28.