Related Research Articles

Heraclius was Byzantine emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Africa, led a revolt against the unpopular emperor Phocas.

The 620s decade ran from January 1, 620, to December 31, 629.

The 610s decade ran from January 1, 610, to December 31, 619.

Year 627 (DCXXVII) was a common year starting on Thursday of the Julian calendar. The denomination 627 for this year has been used since the early medieval period, when the Anno Domini calendar era became the prevalent method in Europe for naming years.

Shahrbaraz, was shah (king) of the Sasanian Empire from 27 April 630 to 9 June 630. He usurped the throne from Ardashir III, and was killed by Iranian nobles after forty days. Before usurping the Sasanian throne he was a spahbed (general) under Khosrow II (590–628). He is furthermore noted for his important role during the climactic Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, and the events that followed afterwards.

The Battle of the Yarmuk was a major battle between the army of the Byzantine Empire and the Arab Muslim forces of the Rashidun Caliphate. The battle consisted of a series of engagements that lasted for six days in August 636, near the Yarmouk River, along what are now the borders of Syria–Jordan and Syria-Israel, southeast of the Sea of Galilee. The result of the battle was a crushing Muslim victory that ended Roman rule in Syria after about seven centuries. The Battle of the Yarmuk is regarded as one of the most decisive battles in military history, and it marked the first great wave of early Muslim conquests after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, heralding the rapid advance of Islam into the then-Christian/Roman Levant.

This is a timeline of major events in the history of Jerusalem; a city that had been fought over sixteen times in its history. During its long history, Jerusalem has been destroyed twice, besieged 23 times, attacked 52 times, and captured and recaptured 44 times.

The Battle of Mu'tah took place in September 629, between the forces of Muhammad and the army of the Byzantine Empire and their Ghassanid vassals. It took place in the village of Mu'tah in Palaestina Salutaris at the east of the Jordan River and modern-day Karak.

The Jewish revolt against Heraclius was part of the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 and is considered the last serious Jewish attempt to gain autonomy in Palaestina Prima prior to modern times.

The Muslim conquest of the Levant, or Muslims conquest of Syria, was a 634–638 CE invasion of Byzantine Syria by the Rashidun Caliphate. A part of the wider Arab-Byzantine Wars, the Levant was brought under Arab Muslim rule and developed into the provincial region of Bilad al-Sham. Clashes between the Arabs and Byzantines on the southern Levantine borders of the Byzantine Empire had occurred during the lifetime of Muhammad, with the Battle of Muʿtah in 629 CE. However, the actual conquest did not begin until 634, two years after Muhammad's death. It was led by the first two Rashidun caliphs who succeeded Muhammad: Abu Bakr and Umar ibn al-Khattab. During this time, Khalid ibn al-Walid was the most important leader of the Rashidun army.

Shahen or Shahin was a senior Sasanian general (spahbed) during the reign of Khosrow II (590–628). He was a member of the House of Spandiyadh.

The Battle of Antioch took place in 613 outside Antioch, Turkey between a Byzantine army led by Emperor Heraclius and a Persian Sassanid army under Generals (spahbed) Shahin and Shahrbaraz as part of the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628. The victorious Persians were able to maintain a hold on the recently taken Byzantine territory. The victory paved the way for a further Sasanian advance into the Levant and Anatolia.

The Sasanian conquest of Jerusalem or Sasanian conquest of Palestine was a significant event in the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, having taken place in early 614. Amidst the conflict, Sasanian king Khosrow II had appointed Shahrbaraz, his spahbod, to lead an offensive into the Diocese of the East of the Byzantine Empire. Under Shahrbaraz, the Sasanian army had secured victories at Antioch as well as at Caesarea Maritima, the administrative capital of Palaestina Prima. By this time, the grand inner harbour had silted up and was useless, but the city continued to be an important maritime hub after Byzantine emperor Anastasius I Dicorus ordered the reconstruction of the outer harbour. Successfully capturing the city and the harbour had given the Sasanian Empire strategic access to the Mediterranean Sea. The Sasanians' advance was accompanied by the outbreak of a Jewish revolt against Heraclius; the Sasanian army was joined by Nehemiah ben Hushiel and Benjamin of Tiberias, who enlisted and armed Jews from across Galilee, including the cities of Tiberias and Nazareth. In total, between 20,000 and 26,000 Jewish rebels took part in the Sasanian assault on Jerusalem. By mid-614, the Jews and the Sasanians had captured the city, but sources vary on whether this occurred without resistance or after a siege and breaching of the wall with artillery. Following the Sasanians capture of Jerusalem tens of thousands of Byzantine Christians were massacred by the Jewish rebels.

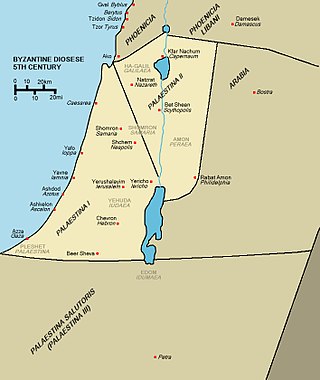

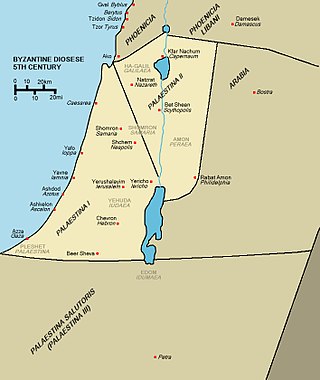

Palaestina Prima or Palaestina I was a Byzantine province that existed from the late 4th century until the Muslim conquest of the Levant in the 630s, in the region of Palestine. It was temporarily lost to the Sassanid Empire in 614, but re-conquered in 628.

Palaestina Secunda or Palaestina II was a province of the Byzantine Empire from 390, until its conquest by the Muslim armies in 634–636. Palaestina Secunda, a part of the Diocese of the East, roughly comprised the Galilee, Yizrael Valley, Bet Shean Valley and southern part of the Golan plateau, with its capital in Scythopolis. The province experienced the rise of Christianity under the Byzantines, but was also a thriving center of Judaism, after the Jews had been driven out of Judea by the Romans in the 1st and 2nd centuries.

The Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 was the final and most devastating of the series of wars fought between the Byzantine / Roman Empire and the Sasanian Empire of Iran. The previous war between the two powers had ended in 591 after Emperor Maurice helped the Sasanian king Khosrow II regain his throne. In 602 Maurice was murdered by his political rival Phocas. Khosrow declared war, ostensibly to avenge the death of the deposed emperor Maurice. This became a decades-long conflict, the longest war in the series, and was fought throughout the Middle East: in Egypt, the Levant, Mesopotamia, the Caucasus, Anatolia, Armenia, the Aegean Sea and before the walls of Constantinople itself.

Nicetas or Niketas was the cousin of Emperor Heraclius. He played a major role in the revolt against Phocas that brought Heraclius to the throne, where he captured Egypt for his cousin. Nicetas remained governor of Egypt thereafter, and participated also in the Byzantine–Sassanid War of 602–628, but failed to stop the Sassanid conquest of Egypt ca. 618/619. He disappears from the sources thereafter, but possibly served as Exarch of Africa until his death.

Domentziolus or Domnitziolus was a nephew of the Byzantine emperor Phocas, appointed curopalates and general in the East during his uncle's reign. He was one of the senior Byzantine military leaders during the opening stages of the Byzantine–Sassanid War of 602–628. His defeats opened the way for the fall of Mesopotamia and Armenia and the invasion of Anatolia by the Persians. In 610, Phocas was overthrown by Heraclius, and Domentziolus was captured but escaped serious harm.

Nehemiah ben Hushiel was described as a leader of the Jewish revolt against Heraclius. Nehemiah ben Hushiel appears in the 7th century Jewish book Sefer Zerubbabel where he represents the Messiah ben Joseph.

Niketas was a 7th-century Byzantine officer. He was the son and heir of the Sasanian Persian general and briefly shahanshah, Shahrbaraz.

References

- ↑ Th. Nöldeke; Grätz, Gesch (1906). Jewish Encyclopedia CHOSROES (KHOSRU) II. PARWIZ ("The Conqueror"). Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ↑ Haim Hillel Ben-Sasson (1976). A History of the Jewish People . Harvard University Press. p. 362. ISBN 9780674397309 . Retrieved 19 January 2014.

nehemiah ben hushiel.

- ↑ Edward Lipiński (2004). Itineraria Phoenicia. Peeters Publishers. pp. 542–543. ISBN 9789042913448 . Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ↑ Walter Emil Kaegi (2003). Heraclius, Emperor of Byzantium. Cambridge University Press. pp. 185, 189. ISBN 9780521814591 . Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ↑ Michael H. Dodgeon; Samuel N. C. Lieu, eds. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars Ad 363-628, Part 2. Taylor & Francis. pp. 227–228.

- ↑ Hagith Sivan (2008). Palestine in Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press. p. 2: Anastasian Landscapes page 8. ISBN 9780191608674 . Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- ↑ Berenbaum, Michael; Skolnik, Fred, eds. (2007). "Benjamin of Tiberias". Encyclopaedia Judaica . Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Detroit: Macmillan Reference. p. 362. ISBN 978-0-02-866097-4 . Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 Alfred Joshua Butler (1902). Arab Conquest of Egypt and the Last Thirty Years of the Roman Dominion. Clarendon Press. p. 134 . Retrieved 21 March 2014.

Egypt jews 630.

- ↑ David Nicolle (1994). Yarmuk AD 636: The Muslim Conquest of Syria. Osprey Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 9781855324145 . Retrieved 21 March 2014.[ permanent dead link ]

- ↑ Eutychius (1896). Eucherius about certain holy places: The library of the Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund in London. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ↑ Elli Kohen (2007). History of the Byzantine Jews: A Microcosmos in the Thousand Year Empire. University Press of America. ISBN 9780761836230 . Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ Lewis, David (2008). God's Crucible: Islam and the Making of Europe, 570–1215 . Norton. p. 69. ISBN 9780393064728.

- ↑ Jewish Encyclopedia BYZANTINE EXPIRE: Heraclius. Jewish Encyclopedia. 1906. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

In atonement for the violation of an oath to the Jews, the monks pledged themselves to a fast, which the Copts still observe; while the Syrians and the Melchite Greeks ceased to keep it after the death of Heraclius; Elijah of Nisibis ("Beweis der Wahrheit des Glaubens," translation by Horst, p. 108, Colmar, 1886) mocks at the observance.

- ↑ Walter Emil Kaegi (2003). Heraclius, Emperor of Byzantium. Cambridge University Press. p. 205. ISBN 9780521814591 . Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ↑ Abu Salih the Armenian; Abu al-Makarim (1895). Basil Thomas Alfred Evetts (ed.). "History of Churches and Monasteries", Abu Salih the Armenian c. 1266 - Part 7 of Anecdota Oxoniensia: Semitic series Anecdota oxoniensia. [Semitic series--pt. VII]. Clarendon Press. pp. 39–.

the emperor Heraclius, on his way to Jerusalem, promised his protection to the Jews of Palestine. (Abu Salih the Armenian, Abu al-Makarim, ed. Evetts 1895, p. 39, Part 7 of Anecdota Oxoniensia: Semitic series Anecdota oxoniensia. Semitic series--pt. VII) (Abu Salih the Armenian was just the Book's owner, the author is actually Abu al-Makarim.)