In quantum mechanics, the uncertainty principle is any of a variety of mathematical inequalities asserting a fundamental limit to the accuracy the values for certain related pairs of physical quantities of a particle, such as position, x, and momentum, p, can be predicted from initial conditions appearing a trade-off between them.

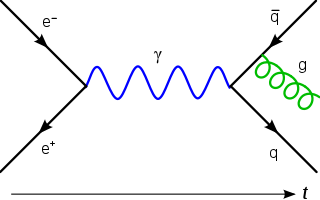

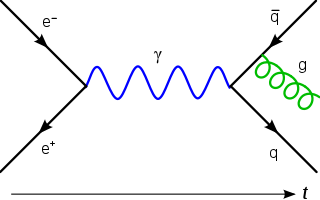

In particle physics, the Dirac equation is a relativistic wave equation derived by British physicist Paul Dirac in 1928. In its free form, or including electromagnetic interactions, it describes all spin-1⁄2 massive particles, called "Dirac particles", such as electrons and quarks for which parity is a symmetry. It is consistent with both the principles of quantum mechanics and the theory of special relativity, and was the first theory to account fully for special relativity in the context of quantum mechanics. It was validated by accounting for the fine structure of the hydrogen spectrum in a completely rigorous way.

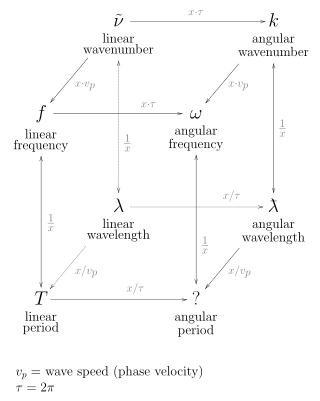

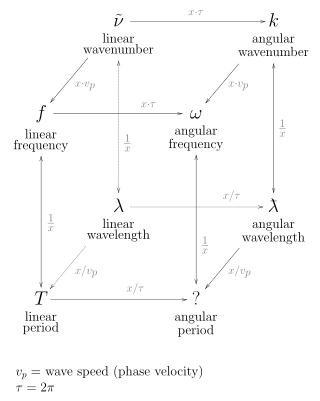

In the physical sciences, the wavenumber, also known as repetency, is the spatial frequency of a wave, measured in cycles per unit distance or radians per unit distance. It is analogous to temporal frequency, which is defined as the number of wave cycles per unit time or radians per unit time.

Hawking radiation is the theoretical thermal black body radiation released outside a black hole's event horizon. This is counterintuitive because once ordinary electromagnetic radiation is inside the event horizon, it cannot escape. It is named after the physicist Stephen Hawking, who developed a theoretical argument for its existence in 1974. Hawking radiation is predicted to be extremely faint and is many orders of magnitude below the current best telescopes' detecting ability.

In physics, specifically in quantum mechanics, a coherent state is the specific quantum state of the quantum harmonic oscillator, often described as a state which has dynamics most closely resembling the oscillatory behavior of a classical harmonic oscillator. It was the first example of quantum dynamics when Erwin Schrödinger derived it in 1926, while searching for solutions of the Schrödinger equation that satisfy the correspondence principle. The quantum harmonic oscillator arise in the quantum theory of a wide range of physical systems. For instance, a coherent state describes the oscillating motion of a particle confined in a quadratic potential well. The coherent state describes a state in a system for which the ground-state wavepacket is displaced from the origin of the system. This state can be related to classical solutions by a particle oscillating with an amplitude equivalent to the displacement.

In physics, black hole thermodynamics is the area of study that seeks to reconcile the laws of thermodynamics with the existence of black hole event horizons. As the study of the statistical mechanics of black-body radiation led to the development of the theory of quantum mechanics, the effort to understand the statistical mechanics of black holes has had a deep impact upon the understanding of quantum gravity, leading to the formulation of the holographic principle.

The black hole information paradox is a puzzle that appears when the predictions of quantum mechanics and general relativity are combined. The theory of general relativity predicts the existence of black holes that are regions of spacetime from which nothing — not even light — can escape. In the 1970s, Stephen Hawking applied the rules of quantum mechanics to such systems and found that an isolated black hole would emit a form of radiation called Hawking radiation. Hawking also argued that the detailed form of the radiation would be independent of the initial state of the black hole, and would depend only on its mass, electric charge and angular momentum.

In particle physics, the Klein–Nishina formula gives the differential cross section of photons scattered from a single free electron, calculated in the lowest order of quantum electrodynamics. It was first derived in 1928 by Oskar Klein and Yoshio Nishina, constituting one of the first successful applications of the Dirac equation. The formula describes both the Thomson scattering of low energy photons and the Compton scattering of high energy photons, showing that the total cross section and expected deflection angle decrease with increasing photon energy.

The old quantum theory is a collection of results from the years 1900–1925 which predate modern quantum mechanics. The theory was never complete or self-consistent, but was rather a set of heuristic corrections to classical mechanics. The theory is now understood as the semi-classical approximation to modern quantum mechanics. The main and final accomplishments of the old quantum theory were the determination of the modern form of the periodic table by Edmund Stoner and the Pauli Exclusion Principle which were both premised on the Arnold Sommerfeld enhancements to the Bohr model of the atom.

In quantum mechanics, a two-state system is a quantum system that can exist in any quantum superposition of two independent quantum states. The Hilbert space describing such a system is two-dimensional. Therefore, a complete basis spanning the space will consist of two independent states. Any two-state system can also be seen as a qubit.

In quantum physics, the spin–orbit interaction is a relativistic interaction of a particle's spin with its motion inside a potential. A key example of this phenomenon is the spin–orbit interaction leading to shifts in an electron's atomic energy levels, due to electromagnetic interaction between the electron's magnetic dipole, its orbital motion, and the electrostatic field of the positively charged nucleus. This phenomenon is detectable as a splitting of spectral lines, which can be thought of as a Zeeman effect product of two relativistic effects: the apparent magnetic field seen from the electron perspective and the magnetic moment of the electron associated with its intrinsic spin. A similar effect, due to the relationship between angular momentum and the strong nuclear force, occurs for protons and neutrons moving inside the nucleus, leading to a shift in their energy levels in the nucleus shell model. In the field of spintronics, spin–orbit effects for electrons in semiconductors and other materials are explored for technological applications. The spin–orbit interaction is at the origin of magnetocrystalline anisotropy and the spin Hall effect.

In physics, Larmor precession is the precession of the magnetic moment of an object about an external magnetic field. The phenomenon is conceptually similar to the precession of a tilted classical gyroscope in an external torque-exerting gravitational field. Objects with a magnetic moment also have angular momentum and effective internal electric current proportional to their angular momentum; these include electrons, protons, other fermions, many atomic and nuclear systems, as well as classical macroscopic systems. The external magnetic field exerts a torque on the magnetic moment,

The theoretical and experimental justification for the Schrödinger equation motivates the discovery of the Schrödinger equation, the equation that describes the dynamics of nonrelativistic particles. The motivation uses photons, which are relativistic particles with dynamics described by Maxwell's equations, as an analogue for all types of particles.

In quantum mechanics, the Pauli equation or Schrödinger–Pauli equation is the formulation of the Schrödinger equation for spin-½ particles, which takes into account the interaction of the particle's spin with an external electromagnetic field. It is the non-relativistic limit of the Dirac equation and can be used where particles are moving at speeds much less than the speed of light, so that relativistic effects can be neglected. It was formulated by Wolfgang Pauli in 1927.

The Planck constant, or Planck's constant, is a fundamental physical constant of foundational importance in quantum mechanics. The constant gives the relationship between the energy of a photon and its frequency, and by the mass-energy equivalence, the relationship between mass and frequency. Specifically, a photon's energy is equal to its frequency multiplied by the Planck constant. The constant is generally denoted by . The reduced Planck constant, or Dirac constant, equal to divided by , is denoted by .

In linear algebra, a raising or lowering operator is an operator that increases or decreases the eigenvalue of another operator. In quantum mechanics, the raising operator is sometimes called the creation operator, and the lowering operator the annihilation operator. Well-known applications of ladder operators in quantum mechanics are in the formalisms of the quantum harmonic oscillator and angular momentum.

Symmetries in quantum mechanics describe features of spacetime and particles which are unchanged under some transformation, in the context of quantum mechanics, relativistic quantum mechanics and quantum field theory, and with applications in the mathematical formulation of the standard model and condensed matter physics. In general, symmetry in physics, invariance, and conservation laws, are fundamentally important constraints for formulating physical theories and models. In practice, they are powerful methods for solving problems and predicting what can happen. While conservation laws do not always give the answer to the problem directly, they form the correct constraints and the first steps to solving a multitude of problems.

The Planck relation is a fundamental equation in quantum mechanics which states that the energy of a photon, E, known as photon energy, is proportional to its frequency, ν:

Magnetic resonance is a quantum mechanical resonant effect that can appear when a magnetic dipole is exposed to a static magnetic field and perturbed with another, oscillating electromagnetic field. Due to the static field, the dipole can assume a number of discrete energy eigenstates, depending on the value of its angular momentum quantum number. The oscillating field can then make the dipole transit between its energy states with a certain probability and at a certain rate. The overall transition probability will depend on the field's frequency and the rate will depend on its amplitude. When the frequency of that field leads to the maximum possible transition probability between two states, a magnetic resonance has been achieved. In that case, the energy of the photons composing the oscillating field matches the energy difference between said states. If the dipole is tickled with a field oscillating far from resonance, it is unlikely to transition. That is analogous to other resonant effects, such as with the forced harmonic oscillator. The periodic transition between the different states is called Rabi cycle and the rate at which that happens is called Rabi frequency. The Rabi frequency should not be confused with the field's own frequency. Since many atomic nuclei species can behave as a magnetic dipole, this resonance technique is the basis of nuclear magnetic resonance, including nuclear magnetic resonance imaging and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

The Nilsson model is a nuclear shell model treating the atomic nucleus as a deformed sphere. In 1953, the first experimental examples were found of rotational bands in nuclei, with their energy levels following the same J(J+1) pattern of energies as in rotating molecules. Quantum mechanically, it is impossible to have a collective rotation of a sphere, so this implied that the shape of these nuclei was nonspherical. In principle, these rotational states could have been described as coherent superpositions of particle-hole excitations in the basis consisting of single-particle states of the spherical potential. But in reality, the description of these states in this manner is intractable, due to the large number of valence particles—and this intractability was even greater in the 1950s, when computing power was extremely rudimentary. For these reasons, Aage Bohr, Ben Mottelson, and Sven Gösta Nilsson constructed models in which the potential was deformed into an ellipsoidal shape. The first successful model of this type is the one now known as the Nilsson model. It is essentially a nuclear shell model using a harmonic oscillator potential, but with anisotropy added, so that the oscillator frequencies along the three Cartesian axes are not all the same. Typically the shape is a prolate ellipsoid, with the axis of symmetry taken to be z.