A flare, also sometimes called a fusée, fusee, or bengala, bengalo in several European countries, is a type of pyrotechnic that produces a bright light or intense heat without an explosion. Flares are used for distress signaling, illumination, or defensive countermeasures in civilian and military applications. Flares may be ground pyrotechnics, projectile pyrotechnics, or parachute-suspended to provide maximum illumination time over a large area. Projectile pyrotechnics may be dropped from aircraft, fired from rocket or artillery, or deployed by flare guns or handheld percussive tubes.

USS Housatonic was a screw sloop-of-war of the United States Navy, gaining its namesake from the Housatonic River of New England.

H. L. Hunley, also known as the Hunley, CSS H. L. Hunley, or CSS Hunley, was a submarine of the Confederate States of America that played a small part in the American Civil War. Hunley demonstrated the advantages and dangers of undersea warfare. She was the first combat submarine to sink a warship (USS Housatonic), although Hunley was not completely submerged and, following her attack, was lost along with her crew before she could return to base. Twenty-one crewmen died in the three sinkings of Hunley during her short career. She was named for her inventor, Horace Lawson Hunley, shortly after she was taken into government service under the control of the Confederate States Army at Charleston, South Carolina.

The Confederate States Navy (CSN) was the naval branch of the Confederate States Armed Forces, established by an act of the Confederate States Congress on February 21, 1861. It was responsible for Confederate naval operations during the American Civil War against the United States's Union Navy.

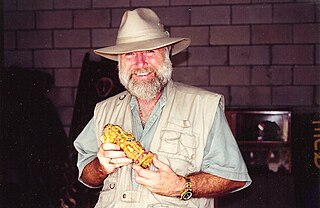

The National Underwater and Marine Agency (NUMA) is a private non-profit organization in the United States founded in 1979. Originally it was a fictional US government organization in the novels of author Clive Cussler. Cussler later created and, until his death in 2020, led the actual organization which is dedicated to "preserving our maritime heritage through the discovery, archaeological survey and conservation of shipwreck artifacts.” Additionally "NUMA does not actively seek private funding. Most of the financial support for the projects comes from the royalties from Clive Cussler’s books."

Horace Lawson Hunley was a Confederate marine engineer during the American Civil War. He developed early hand-powered submarines, the most famous of which was posthumously named for him, 'H. L. Hunley'.

A spar torpedo is a weapon consisting of a bomb placed at the end of a long pole, or spar, and attached to a boat. The weapon is used by running the end of the spar into the enemy ship. Spar torpedoes were often equipped with a barbed spear at the end, so it would stick to wooden hulls. A fuse could then be used to detonate it.

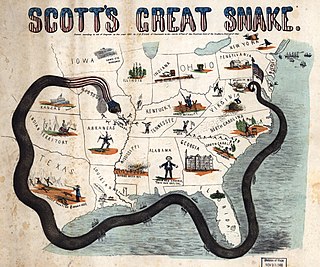

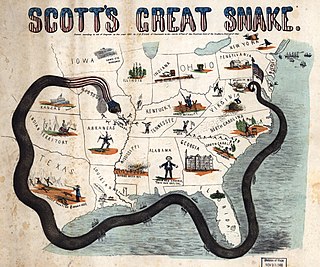

The Union blockade in the American Civil War was a naval strategy by the United States to prevent the Confederacy from trading.

A signal lamp is a visual signaling device for optical communication by flashes of a lamp, typically using Morse code. The idea of flashing dots and dashes from a lantern was first put into practice by Captain Philip Howard Colomb, of the Royal Navy, in 1867. Colomb's design used limelight for illumination, and his original code was not the same as Morse code. During World War I, German signalers used optical Morse transmitters called Blinkgerät, with a range of up to 8 km (5 miles) at night, using red filters for undetected communications.

Blue Light or Blue light may refer to:

John Baptist Smith (1843–1923) is believed by some to have provided the most lasting contribution made by either side during the American Civil War. In 1862 he invented and helped build a lantern system of naval signaling.

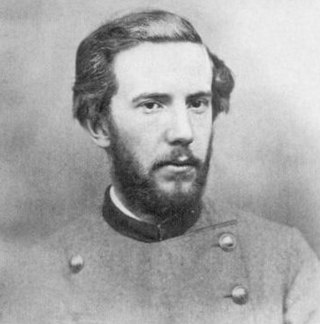

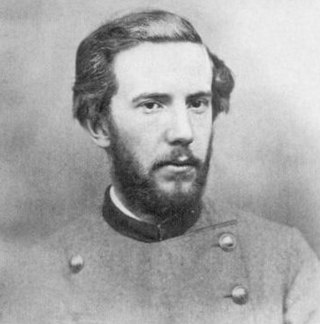

George Erasmus Dixon was a first lieutenant in the Confederate Army in the American Civil War. He is best known as the commander of the Confederate submarine H.L. Hunley during her successful mission to sink the Union blockading ship USS Housatonic off Charleston, South Carolina.

Charleston, South Carolina, was a hotbed of secession at the start of the American Civil War and an important Atlantic Ocean port city for the fledgling Confederate States of America. The first shots against the Federal government were those fired there by cadets of the Citadel to stop a ship from resupplying the Federally held Fort Sumter. Three months later, the bombardment of Fort Sumter triggered a massive call for Federal troops to put down the rebellion. Although the city and its surrounding fortifications were repeatedly targeted by the Union Army and Navy, Charleston did not fall to Federal forces until the last months of the war. Charleston was devastated.

Edward Lee Spence is a pioneer in underwater archaeology who studies shipwrecks and sunken treasure. He is also a published editor and author of non-fiction reference books; a magazine editor, and magazine publisher ; and a published photographer. Spence was twelve years old when he found his first five shipwrecks.

USS G. W. Blunt was a Sandy Hook pilot boat acquired by the Union Navy during the American Civil War in 1861. See George W. Blunt (1856) for more details. She was used by the Union Navy as a gunboat as well as a dispatch boat in support of the Union Navy blockade of Confederate waterways.

Martha Jane Coston was an American inventor and businesswoman who invented the Coston flare, a device for signaling at sea, and the owner of the Coston Manufacturing Company.

The Sinking of USS Housatonic on 17 February 1864 during the American Civil War was an important turning point in naval warfare. The Confederate States Navy submarine, H.L. Hunley made her first and only attack on a Union Navy warship when she staged a clandestine night attack on USS Housatonic in Charleston harbor. H.L. Hunley approached just under the surface, avoiding detection until the last moments, then embedded and remotely detonated a spar torpedo that rapidly sank the 1,240 long tons (1,260 t) sloop-of-war with the loss of five Union sailors. H.L. Hunley became renowned as the first submarine to successfully sink an enemy vessel in combat, and was the direct progenitor of what would eventually become international submarine warfare, although the victory was Pyrrhic and short-lived, since the submarine did not survive the attack and was lost with all eight Confederate crewmen.

Conrad Wise Chapman was an American painter who served in the Confederate States Army from 1861 to 1865.

Robert Francis Flemming Jr. was an American inventor and Union sailor in the American Civil War. He was the first crew member aboard the USS Housatonic to spot the H.L. Hunley before it sank the USS Housatonic. The sinking of USS Housatonic is renowned as the first sinking of an enemy ship in combat by a submarine.

The conservation-restoration of the H.L. Hunley is currently being undertaken by the Warren Lasch Conservation Center; they hope to have the Hunley project completed by 2020. Since the Hunley was located in 1970 by Dr. E. Lee Spence and recovered from the ocean in 2000, a team of conservators from the Lasch Conservation Center has been working to restore the Hunley.