Human capital flight is the emigration or immigration of individuals who have received advanced training at home. The net benefits of human capital flight for the receiving country are sometimes referred to as a "brain gain" whereas the net costs for the sending country are sometimes referred to as a "brain drain". In occupations with a surplus of graduates, immigration of foreign-trained professionals can aggravate the underemployment of domestic graduates, whereas emigration from an area with a surplus of trained people leads to better opportunities for those remaining. But emigration may cause problems for the home country if the trained people are in short supply there.

Human migration is the movement of people from one place to another with intentions of settling, permanently or temporarily, at a new location.

A skilled worker is any worker who has special skill, training, knowledge which they can then apply to their work. A skilled worker may have learned their skills through work experience, on-the-job training, an apprenticeship program or formal education. These skills often lead to better outcomes economically. The definition of a skilled worker has seen change throughout the 20th century, largely due to the industrial impact of the Great Depression and World War II. Further changes in globalisation have seen this definition shift further in Western countries, with many jobs moving from manufacturing based sectors to more advanced technical and service based roles. Examples of formal educated skilled labor include engineers, scientists, doctors and teachers, while examples of informal educated workers include crane operators, CDL truck drivers, machinists, drafters, plumbers, craftsmen, cooks and bookkeepers.

The Australian diaspora are those Australians living outside of Australia. It includes approximately 598,765 Australian-born people living outside of Australia, people who are Australian citizens and live outside Australia, and people with Australian ancestry who live outside of Australia.

Immigration is the international movement of people to a destination country of which they are not usual residents or where they do not possess nationality in order to settle as permanent residents. Commuters, tourists, and other short-term stays in a destination country do not fall under the definition of immigration or migration; seasonal labour immigration is sometimes included, however.

The economic results of migration impact the economies of both the sending and receiving countries.

Reverse brain drain is a form of brain drain where human capital moves in reverse from a more developed country to a less developed country that is developing rapidly. These migrants may accumulate savings, also known as remittances, and develop skills overseas that can be used in their home country.

Circular migration or repeat migration is the temporary and usually repetitive movement of a migrant worker between home and host areas, typically for the purpose of employment. It represents an established pattern of population mobility, whether cross-country or rural-urban. There are several benefits associated with this migration pattern, including gains in financial capital, human capital, and social capital. There are also costs associated with circular migration, such as brain drain, poor working conditions, forced labor, and the inability to transfer acquired skills to home economies. Socially, there are strong connections to gender, health outcomes, development, poverty, and global immigration policy.

International migration occurs when people cross state boundaries and stay in the host state for some minimum length of the time. Migration occurs for many reasons. Many people leave their home countries in order to look for economic opportunities in another country. Others migrate to be with family members who have migrated or because of political conditions in their countries. Education is another reason for international migration, as students pursue their studies abroad, although this migration is sometimes temporary, with a return to the home country after the studies are completed.

Maurice Kugler is a Colombian American economist born in 1967. He received his Ph.D. in economics from UC Berkeley in 2000, as well as an M.Sc. (Econ) and a B.Sc. (Econ) both from the London School of Economics. Kugler is professor of public policy in the Schar School of Policy and Government at George Mason University. Prior to this, he worked as a consultant for the World Bank, where he was senior economist before (2010-2012). Most recently he was principal research scientist and managing director at IMPAQ International.

Human capital flight from Iran has been a significant phenomenon since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Iran had a substantial drain of highly skilled and educated individuals in the early 1990s. More than 150,000 Iranians left the Islamic Republic every year in the early 1990s, and an estimated 25 percent of all Iranians with post-secondary education then lived abroad in OECD-standard developed countries. A 2009 IMF report indicated that Iran tops the list of countries that are losing their academic elite, with a loss of 150,000 to 180,000 specialists—roughly equivalent to a capital loss of US$50 billion. In addition, the political crackdown following the 2009 Iranian election protests is said to have created a "spreading refugee exodus" of Iranian intelligentsia. It has also been reported that the Central Intelligence Agency of the United States is running a covert operation code-named "Braindrain Project" with the aim of luring away nuclear-oriented Iranian talent, thus undermining Iran's nuclear program.

The labor migration policy of the Philippine government allows and encourages emigration. The Department of Foreign Affairs, which is one of the government's arms of emigration, grants Filipinos passports that allow entry to foreign countries. In 1952, the Philippine government formed the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA) as the agency responsible for opening the benefits of the overseas employment program. In 1995, it enacted the Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipino Act in order to "institute the policies of overseas employment and establish a higher standard of protection and promotion of the welfare of migrant workers and their families and overseas Filipinos in distress." In 2022, the Department of Migrant Workers was formed, incorporating the POEA with its functions and mandate becoming the backbone of the new executive department.

David McKenzie is a lead economist at the World Bank's Development Research Group, Finance and Private Sector Development Unit in Washington, D.C. His research topics include migration, microenterprises, and methodology for use with developing country data.

Zimbabwean Canadians are Canadian citizens of Zimbabwean descent or a Zimbabwe-born person who resides in Canada. According to the Canada 2016 Census there were 16,225 Canadian citizens who claimed Zimbabwean ancestry and 15,000 Zimbabwean citizens residing in the country at the moment of the census.

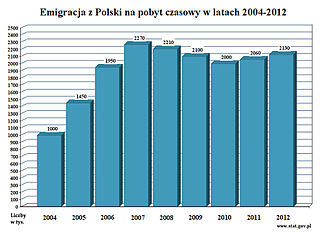

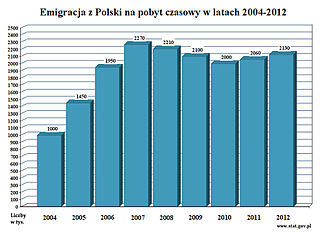

Since the fall of communism in 1989, the nature of migration to and from Poland has been in flux. After Poland's accession to the European Union and accession to the Schengen Area in particular, a significant number of Poles, estimated at over two million, have emigrated, primarily to the United Kingdom, Germany, France and Ireland. The majority of them, according to the Central Statistical Office of Poland, left in search of better work opportunities abroad while retaining permanent resident status in Poland itself.

The Malaysian diaspora are Malaysian emigrants from Malaysia and their descendants that reside in a foreign country. Population estimates vary from seven hundred thousand to one million, both descendants of early emigrants from Malaysia, as well as more recent emigrants from Malaysia. The largest of these foreign communities are in Singapore, Australia, Brunei and the United Kingdom.

Christian Dustmann, FBA, is a German economist who currently serves as Professor of Economics at the Department of Economics of University College London. There, he also works as Director of the Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration (CReAM), which he helped found. Dustmann belongs to the world's foremost labour economists and migration scholars.

Hillel Rapoport is an economist at the University of Paris 1 Pantheon-Sorbonne and Paris School of Economics. He specializes on the dynamics of migration and its impact on economic development as well as on the economics of immigration, diversity, and refugees' relocation and resettlement and ranks as one of the leading economists on the topic of migration.

Frédéric Docquier is a Belgian economist and Professor of Economics at the Catholic University of Louvain (UCLouvain). He ranks as one of the leading economists in the field of international migration, with a focus on brain drain and skilled migration.

Brain drain from Nigeria, nicknamed Japa is the exodus of middle-class and highly skilled Nigerians which has been occurring in waves since the late 1980s to early 1990s. This trend was initially restricted to certain professions but has now become free for all with the introduction of visa programs in order to fill workforce gaps in developed nations. This was sparked by an economic downturn following a period of economic boom in the 1970s and 1980s propelled by the discovery of oil wells in Nigeria.