The insanity defense, also known as the mental disorder defense, is an affirmative defense by excuse in a criminal case, arguing that the defendant is not responsible for their actions due to a psychiatric disease at the time of the criminal act. This is contrasted with an excuse of provocation, in which the defendant is responsible, but the responsibility is lessened due to a temporary mental state. It is also contrasted with the justification of self defense or with the mitigation of imperfect self-defense. The insanity defense is also contrasted with a finding that a defendant cannot stand trial in a criminal case because a mental disease prevents them from effectively assisting counsel, from a civil finding in trusts and estates where a will is nullified because it was made when a mental disorder prevented a testator from recognizing the natural objects of their bounty, and from involuntary civil commitment to a mental institution, when anyone is found to be gravely disabled or to be a danger to themself or to others.

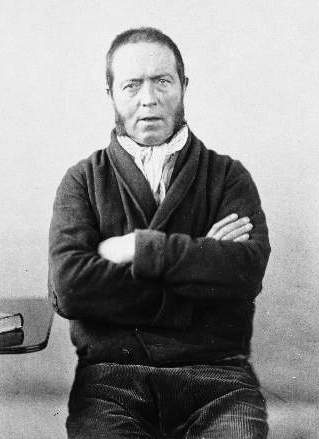

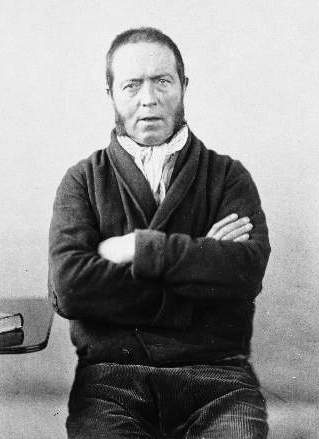

The M'Naghten rule(s) (pronounced, and sometimes spelled, McNaughton) is a legal test defining the defence of insanity that was formulated by the House of Lords in 1843. It is the established standard in UK criminal law. Versions have been adopted in some US states, currently or formerly, and other jurisdictions, either as case law or by statute. Its original wording is a proposed jury instruction:

that every man is to be presumed to be sane, and ... that to establish a defence on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.

In criminal law, actus reus, Latin for "guilty act", is one of the elements normally required to prove commission of a crime in common law jurisdictions, the other being Latin: mens rea. In the United States, it is sometimes called the external element or the objective element of a crime.

In criminal law, diminished responsibility is a potential defense by excuse by which defendants argue that although they broke the law, they should not be held fully criminally liable for doing so, as their mental functions were "diminished" or impaired.

In criminal law, automatism is a rarely used criminal defence. It is one of the mental condition defences that relate to the mental state of the defendant. Automatism can be seen variously as lack of voluntariness, lack of culpability (unconsciousness) or excuse. Automatism means that the defendant was not aware of his or her actions when making the particular movements that constituted the illegal act.

R v Daviault [1994] 3 S.C.R. 63, is a Supreme Court of Canada decision on the availability of the defence of intoxication for "general intent" criminal offences. The Leary rule which eliminated the defence was found unconstitutional in violation of both section 7 and 11(d) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Instead, intoxication can only be used as a defence where it is so extreme that it is akin to automatism or insanity.

The criminal law of Canada is under the exclusive legislative jurisdiction of the Parliament of Canada. The power to enact criminal law is derived from section 91(27) of the Constitution Act, 1867. Most criminal laws have been codified in the Criminal Code, as well as the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, Youth Criminal Justice Act and several other peripheral statutes.

R v Parks, [1992] 2 S.C.R. 871 is a leading Supreme Court of Canada decision on the criminal automatism defence.

In English law, diminished responsibility is one of the partial defenses that reduce the offense from murder to manslaughter if successful. This allows the judge sentencing discretion, e.g. to impose a hospital order under section 37 of the Mental Health Act 1983 to ensure treatment rather than punishment in appropriate cases. Thus, when the actus reus of death is accompanied by an objective or constructive version of mens rea, the subjective evidence that the defendant did intend to kill or cause grievous bodily harm because of a mental incapacity will partially excuse his conduct. Under s.2(2) of the Homicide Act 1957 the burden of proof is on the defendant to the balance of probabilities. The M'Naghten Rules lack a volitional limb of "irresistible impulse"; diminished responsibility is the volitional mental condition defense in English criminal law.

R v Quick [1973] QB 910 is an English criminal case, as to sane automatism and the sub-category of self-inducement of such a state. The court ruled that it may not be used as a defence if the defendant's loss of self-control was on the part of negligence in consuming or not consuming something which someone ought to but the jury must be properly directed so as to make all relevant findings of fact. The ruling stresses that automatism is usually easily distinct from insanity, in the few cases where the lines are blurred it is a complex problem for prosecutors and mental health professionals.

R v Bailey is a 1983 decision of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales considering criminal responsibility as to non-insane automatism. The broad questions addressed were whether a hampered state of mind, which the accused may have a legal and moral duty to lessen or avoid, gave him a legal excuse for his actions; and whether as to any incapacity there was strong countering evidence on the facts involved. The court ruled that the jury had been misdirected as to the effect of a defendant's mental state on his criminal liability. However, Bailey's defence had not been supported by sufficient evidence to support an acquittal and his appeal was dismissed.

English criminal law concerns offences, their prevention and the consequences, in England and Wales. Criminal conduct is considered to be a wrong against the whole of a community, rather than just the private individuals affected. The state, in addition to certain international organisations, has responsibility for crime prevention, for bringing the culprits to justice, and for dealing with convicted offenders. The police, the criminal courts and prisons are all publicly funded services, though the main focus of criminal law concerns the role of the courts, how they apply criminal statutes and common law, and why some forms of behaviour are considered criminal. The fundamentals of a crime are a guilty act and a guilty mental state. The traditional view is that moral culpability requires that a defendant should have recognised or intended that they were acting wrongly, although in modern regulation a large number of offences relating to road traffic, environmental damage, financial services and corporations, create strict liability that can be proven simply by the guilty act.

Settled insanity is defined as a permanent or "settled" condition caused by long-term substance abuse and differs from the temporary state of intoxication. In some United States jurisdictions "settled insanity" can be used as a basis for an insanity defense, even though voluntary intoxication cannot, if the "settled insanity" negates one of the required elements of the crime such as malice aforethought. However, U.S. federal and state courts have differed in their interpretations of when the use of "settled insanity" is acceptable as an insanity defense and also over what is included in the concept of "settled insanity".

Fault, as a legal term, refers to legal blameworthiness and responsibility in each area of law. It refers to both the actus reus and the mental state of the defendant. The basic principle is that a defendant should be able to contemplate the harm that his actions may cause, and therefore should aim to avoid such actions. Different forms of liability employ different notions of fault, in some there is no need to prove fault, but the absence of it.

Ross v HM Advocate1991 JC 210 is a leading Scots criminal case that concerns automatism as defence. The High Court of Justiciary clarified the rules for an accused to successfully argue automatism as a defence to a criminal charge.

Intoxication in English law is a circumstance which may alter the capacity of a defendant to form mens rea, where a charge is one of specific intent, or may entirely negate mens rea where the intoxication is involuntary. The fact that a defendant is intoxicated in the commission of a crime — whether voluntarily or not — has never been regarded as a full defence to criminal proceedings. Its development at common law has been shaped by the acceptance that intoxicated individuals do not think or act as rationally as they would otherwise, but also by a public policy necessity to punish individuals who commit crimes.

Voluntary intoxication, where a defendant has wilfully consumed drink or drugs before committing acts which constitute the prohibited conduct of an offence, has posed a considerable problem for the English criminal law. There is a correspondence between incidence of drinking and crimes of violence, such as assaults and stabbings. Accordingly, there is a debate about the effect of voluntary intoxication on the mental element of crimes, which is often that the defendant foresaw the consequences, or that they intended them.

South African criminal law is the body of national law relating to crime in South Africa. In the definition of Van der Walt et al., a crime is "conduct which common or statute law prohibits and expressly or impliedly subjects to punishment remissible by the state alone and which the offender cannot avoid by his own act once he has been convicted." Crime involves the infliction of harm against society. The function or object of criminal law is to provide a social mechanism with which to coerce members of society to abstain from conduct that is harmful to the interests of society.

In S v Chretien, an important case in South African criminal law, especially as it pertains to the defence of automatism, the Appellate Division held that even automatism arising out of voluntary intoxication may constitute an absolute defence, leading to a total acquittal, where, inter alia, the accused drinks so much that they lack criminal capacity.

R v Brown, 2022 SCC 18, is a decision of the Supreme Court of Canada on the constitutionality of section 33.1 of the Criminal Code, which prohibited an accused from raising self-induced intoxication as a defence to criminal charges. The Court unanimously held that the section violated the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and struck it down as unconstitutional. The Court delivered the Brown decision alongside the decision for its companion case R v Sullivan.