The Brown Fellowship Society (1790-1945), which became the Century Fellowship Society, was an African-American self-help organization in South Carolina. It eventually became the Century Fellowship Society.

The Brown Fellowship Society (1790-1945), which became the Century Fellowship Society, was an African-American self-help organization in South Carolina. It eventually became the Century Fellowship Society.

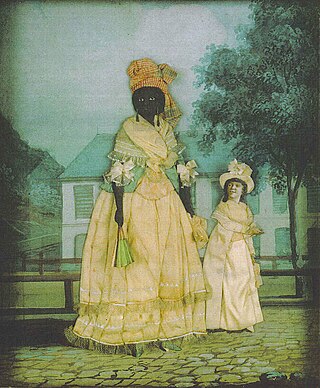

The Brown Fellowship Society was founded in Charleston, South Carolina in 1790 with the motto “Charity and Benevolence”. It was founded by five free non-whites who attended St. Philip’s Episcopal Church: James Mitchell, George Bampfield, William Cattel, George Bedon, and Samuel Saltus. It was founded “to provide benefits which the white church denied them like a proper burial ground, widow and orphan care, and assistance in times of sickness”. [1] The group’s cemetery was an important part of its function. Those who joined the club considered themselves “brown”, mulattoes, an important distinction at the time when society in Charleston recognized three races: White, Mulatto, and Negro, including octoroons and quadroons. [2]

Unlike some mutual self-help organization in the African-American community, the Brown Society was not linked to any church, even banning discussion of religion. Many of the members of the Brown Fellowship Society had their own businesses and some were prosperous. In 1843, another group was formed by African American men in Charleston, the Humane Brotherhood, modeled after the Brown Fellowship Society, but less class conscious. [1]

The Brown Fellowship Society did not intervene in the status of slaves at the time. The organization was focused on creating a cemetery for "brown" black people. The Society was able to buy a ground for the cemetery and a meeting house. The Society had merely 50 members. Each had to pay a $50 membership fee, and went through three different votes before being admitted. [2] The organization forbid talks about political or religious matters. The organization also cared for widows of members, provided a primary school, supported its members' businesses, and lobbied towards the white society. [3]

"After the Civil War, the Brown Fellowship Society expanded to include more African Americans, including women and those of darker skin". [2] [3]

In 1892, The Society was renamed the Century Fellowship Society. [3]

In 1943, the city of Charleston passed an ordinance prohibiting private organizations from maintaining graveyards. The Century Fellowship Society sold the original BFS cemetery in 1945 to Bishop England High School, [3] and the Society was officially dissolved.

For many years afterwards, the Catholic Diocese kept affirming that the cemetery had been cleared of corpses, but in 2001, four gravesites were discovered when the construction of the College of Charleston's Addlestone Library was launched. [4] The whole cemetery was paved over. The records of the society are held at the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture. [3]

In 1843, the free black man Thomas Smalls applied for a membership in the Brown Fellowship Society and was turned down because he was too black. He set up his own society, The Society for Free Blacks of Dark Complexion (later renamed the Brotherly Society). He opened a graveyard for pure African descent, the MacPhelah cemetery, adjacent to the Brown Fellowship Graveyard, and another one, Ephrath (still intact today). [3]

Mulatto is a racial classification to refer to people of mixed African and European ancestry. Its use is considered outdated and offensive in several languages, including English and Dutch, whereas in languages such as Italian, Spanish and Portuguese it is not, and can even be a source of pride. A mulatta is a female mulatto.

Melungeons are a group of people from Appalachia who predominantly descend from northern or central Europeans and sub-Saharan Africans. Their White ancestors were likely brought to Virginia as indentured servants in the mid-17th century.

An African American is a citizen or resident of the United States who has origins in any of the black populations of Africa. African American-related topics include:

Denmark Vesey was an 18th-century and early 19th century free Black and community leader in Charleston, South Carolina, who was accused and convicted of planning a major slave revolt in 1822. Although the alleged plot was discovered before it could be realized, its potential scale stoked the fears of the antebellum planter class that led to increased restrictions on both enslaved and free African Americans.

Robert Carlos De Large was a Republican member of the United States House of Representatives from South Carolina, serving 1871 to 1873. He was earlier a delegate to the 1868 state constitutional convention and elected in 1868 to the South Carolina House of Representatives for one term.

In the British colonies in North America and in the United States before the abolition of slavery in 1865, free Negro or free Black described the legal status of African Americans who were not enslaved. The term was applied both to formerly enslaved people (freedmen) and to those who had been born free, whether of African or mixed descent.

South Carolina was one of the Thirteen Colonies that first formed the United States. European exploration of the area began in April 1540 with the Hernando de Soto expedition, which unwittingly introduced diseases that decimated the local Native American population. In 1663, the English Crown granted land to eight proprietors of what became the colony. The first settlers came to the Province of Carolina at the port of Charleston in 1670. They were mostly wealthy planters and their slaves coming from the English Caribbean colony of Barbados. By 1700 the colony was exporting deerskin, cattle, rice, and naval stores. The Province of Carolina was split into North and South Carolina in 1712. Pushing back the Native Americans in the Yamasee War (1715–1717), colonists next overthrew the proprietors' rule in the Revolution of 1719, seeking more direct representation. In 1719, South Carolina became a crown colony.

The American Missionary Association (AMA) was a Protestant-based abolitionist group founded on September 3, 1846 in Albany, New York. The main purpose of the organization was abolition of slavery, education of African Americans, promotion of racial equality, and spreading Christian values. Its members and leaders were of both races; The Association was chiefly sponsored by the Congregationalist churches in New England. The main goals were to abolish slavery, provide education to African Americans, and promote racial equality for free Blacks. The AMA played a significant role in several key historical events and movements, including the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Civil Rights Movement.

Partus sequitur ventrem was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies in the Americas which defined the legal status of children born there; the doctrine mandated that children of slave mothers would inherit the legal status of their mothers. As such, children of enslaved women would be born into slavery. The legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem was derived from Roman civil law, specifically the portions concerning slavery and personal property (chattels), as well as the common law of personal property.

Thomas Ezekiel Miller was an American educator, lawyer and politician. After being elected as a state legislator in South Carolina, he was one of only five African Americans elected to Congress from the South in the Jim Crow era of the last decade of the nineteenth century, as disfranchisement reduced black voting. After that, no African Americans were elected from the South until 1972.

Approximately 15.3% of Americans identify as Baptist, making Baptists the second-largest religious group in the United States, after Roman Catholics. Baptists adhere to a congregationalist structure, so local church congregations are generally self-regulating and autonomous, meaning that their broadly Christian religious beliefs can and do vary. Baptists make up a significant portion of evangelicals in the United States and approximately one third of all Protestants in the United States. Divisions among Baptists have resulted in numerous Baptist bodies, some with long histories and others more recently organized. There are also many Baptists operating independently or practicing their faith in entirely independent congregations.

The Moors Sundry Act of 1790 was a 1790 advisory resolution passed by South Carolina House of Representatives, clarifying the status of free subjects of the Sultan of Morocco, Mohammed ben Abdallah. The resolution offered the opinion that free citizens of Morocco were not subject to laws governing blacks and slaves.

John Marrant was an American Methodist preacher and missionary and one of the first black preachers in North America. Born free in New York City, he moved as a child with his family to Charleston, South Carolina. His father died when he was young, and he and his mother also lived in Florida and Georgia. After escaping to the Cherokee, with whom he lived for two years, he allied with the British during the American Revolutionary War and resettled afterward in London. There he became involved with the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion and ordained as a preacher.

The civil rights movement (1865-1896) aimed to eliminate racial discrimination against African Americans, improve their educational and employment opportunities, and establish their electoral power, just after the abolition of slavery in the United States. The period from 1865 to 1895 saw a tremendous change in the fortunes of the black community following the elimination of slavery in the South.

The history of Charleston, South Carolina, is one of the longest and most diverse of any community in the United States, spanning hundreds of years of physical settlement beginning in 1670. Charleston was one of leading cities in the South from the colonial era to the Civil War in the 1860s. The city grew wealthy through the export of rice and, later, sea island cotton and it was the base for many wealthy merchants and landowners. Charleston was the capital of American slavery.

The following is a timeline of the history of Charleston, South Carolina, USA.

Black South Carolinians are residents of the state of South Carolina who are of African ancestry. This article examines South Carolina's history with an emphasis on the lives, status, and contributions of African Americans. Enslaved Africans first arrived in the region in 1526, and the institution of slavery remained until the end of the Civil War in 1865. Until slavery's abolition, the free black population of South Carolina never exceeded 2%. Beginning during the Reconstruction Era, African Americans were elected to political offices in large numbers, leading to South Carolina's first majority-black government. Toward the end of the 1870s however, the Democratic Party regained power and passed laws aimed at disenfranchising African Americans, including the denial of the right to vote. Between the 1870s and 1960s, African Americans and whites lived segregated lives; people of color and whites were not allowed to attend the same schools or share public facilities. African Americans were treated as second-class citizens leading to the civil rights movement in the 1960s. In modern America, African Americans constitute 22% of the state's legislature, and in 2014, the state's first African American U.S. Senator since Reconstruction, Tim Scott, was elected. In 2015, the Confederate flag was removed from the South Carolina Statehouse after the Charleston church shooting.

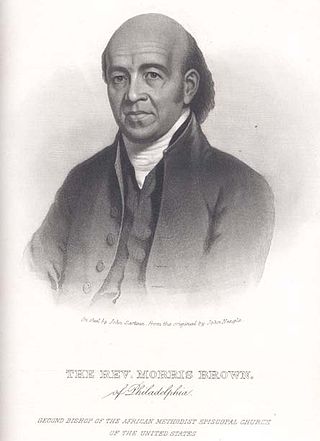

Morris Brown was one of the founders of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and its second presiding bishop. He founded Emanuel AME Church in his native Charleston, South Carolina. It was implicated in the slave uprising planned by Denmark Vesey, also of this church, and after that was suppressed, Brown was imprisoned for nearly a year. He was never convicted of a crime.

The Negro Law of South Carolina (1848) was one of John Belton O'Neall's longer works.

Richard Edward Dereef (1798–1876) was a former black slave who would eventually gain freedom and become owner of forty black slaves, American lumber trader, and politician. A member of a wealthy mulatto family, Dereef was a prominent member of South Carolinian society but was subject to discrimination due to his race. He was considered one of the wealthiest black men in Charleston, South Carolina and served as a city alderman during the Reconstruction era.