The Picts were a group of peoples in what is now Scotland north of the Firth of Forth, in the Early Middle Ages. Where they lived and details of their culture can be gleaned from early medieval texts and Pictish stones. The name Picti appears in written records as an exonym from the late third century AD. They are assumed to have been descendants of the Caledonii and other northern Iron Age tribes. Their territory is referred to as "Pictland" by modern historians. Initially made up of several chiefdoms, it came to be dominated by the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu from the seventh century. During this Verturian hegemony, Picti was adopted as an endonym. This lasted around 160 years until the Pictish kingdom merged with that of Dál Riata to form the Kingdom of Alba, ruled by the House of Alpin. The concept of "Pictish kingship" continued for a few decades until it was abandoned during the reign of Caustantín mac Áeda.

Burghead is a small town in Moray, Scotland, about 8 miles (13 km) north-west of Elgin. The town is mainly built on a peninsula that projects north-westward into the Moray Firth, surrounding it by water on three sides. People from Burghead are called Brochers.

The Brough of Birsay is an uninhabited tidal island off the north-west coast of The Mainland of Orkney, Scotland, in the parish of Birsay. It is located around 13 miles north of Stromness and features the remains of Pictish and Norse settlements as well as a modern lighthouse.

A Pictish stone is a type of monumental stele, generally carved or incised with symbols or designs. A few have ogham inscriptions. Located in Scotland, mostly north of the Clyde-Forth line and on the Eastern side of the country, these stones are the most visible remaining evidence of the Picts and are thought to date from the 6th to 9th century, a period during which the Picts became Christianized. The earlier stones have no parallels from the rest of the British Isles, but the later forms are variations within a wider Insular tradition of monumental stones such as high crosses. About 350 objects classified as Pictish stones have survived, the earlier examples of which holding by far the greatest number of surviving examples of the mysterious symbols, which have long intrigued scholars.

Portmahomack is a small fishing village in Easter Ross, Scotland. It is situated in the Tarbat Peninsula in the parish of Tarbat. Tarbat Ness Lighthouse is about three miles from the village at the end of the Tarbat Peninsula. Ballone Castle lies about one mile from the village.

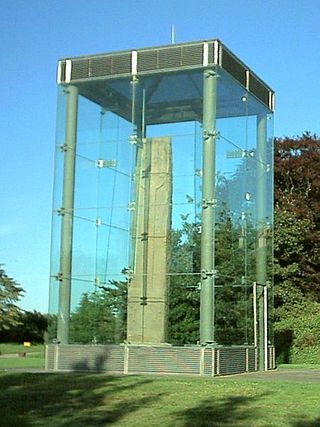

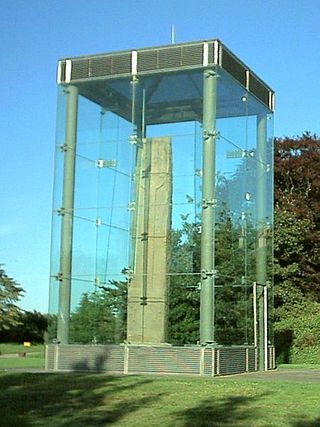

Sueno's Stone is a Picto-Scottish Class III standing stone on the north-easterly edge of Forres in Moray and is the largest surviving Pictish style cross-slab stone of its type in Scotland, standing 6.5 metres in height. It is situated on a raised bank on a now isolated section of the former road to Findhorn. The stone is named after Sweyn Forkbeard, but this association has been challenged and it has also been associated with the killing of King Dubh mac Ailpin in Forres in 966. The stone was erected c. 850–950 but by whom and for what, is unknown.

Fortriu was a Pictish kingdom recorded between the 4th and 10th centuries. It was traditionally believed to be located in and around Strathearn in central Scotland, but is more likely to have been based in the north, in the Moray and Easter Ross area. Fortriu is a term used by historians as it is not known what name its people used to refer to their polity. Historians also sometimes use the name synonymously with Pictland in general.

Bridei son of Beli, died 692 was king of Fortriu and of the Picts from 671 until 692. His reign marks the start of the period known to historians as the Verturian hegemony, a turning point in the history of Scotland, when the uniting of Pictish provinces under the over-kingship of the kings of Fortriu saw the development of a strong Pictish state and identity encompassing most of the peoples north of the Forth.

Duffus is a village and parish in Moray, Scotland.

Scotland was divided into a series of kingdoms in the Early Middle Ages, i.e. between the end of Roman authority in southern and central Britain from around 400 AD and the rise of the kingdom of Alba in 900 AD. Of these, the four most important to emerge were the Picts, the Gaels of Dál Riata, the Britons of Alt Clut, and the Anglian kingdom of Bernicia. After the arrival of the Vikings in the late 8th century, Scandinavian rulers and colonies were established on the islands and along parts of the coasts. In the 9th century, the House of Alpin combined the lands of the Scots and Picts to form a single kingdom which constituted the basis of the Kingdom of Scotland.

The Broch of Gurness is an Iron Age broch village on the northeast coast of Mainland Orkney in Scotland overlooking Eynhallow Sound, about 15 miles north-west of Kirkwall. It once housed a substantial community.

Kinneddar is a small settlement on the outskirts of Lossiemouth in Moray, Scotland, near the main entrance to RAF Lossiemouth. Long predating the modern town of Lossiemouth, Kinneddar was a major monastic centre for the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu from the 6th or 7th centuries, and the source of the important collection of Pictish stones called the Drainie Carved Stones. The Kirk of Kinneddar was the cathedral of the Diocese of Moray between 1187 and 1208, and remained an important centre of diocesan administration and residence of the Bishop of Moray through the 13th and 14th centuries.

The fort of Clatchard Craig was located on a hill of the same name by the Tay. A human presence on the site has been identified from the neolithic period onward and the fort itself was occupied from the sixth century AD until at least the eighth century. It stood close to several places which were centres of secular and religious power during the early Middle Ages including Abernethy, Forteviot, Scone and Moncreiffe. As such it seems to have been an important stronghold of the Picts.

Hillforts in Scotland are earthworks, sometimes with wooden or stone enclosures, built on higher ground, which usually include a significant settlement, built within the modern boundaries of Scotland. They were first studied in the eighteenth century and the first serious field research was undertaken in the nineteenth century. In the twentieth century there were large numbers of archaeological investigations of specific sites, with an emphasis on establishing a chronology of the forts. Forts have been classified by type and their military and ritual functions have been debated.

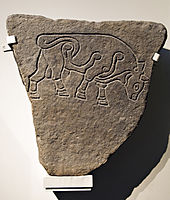

The Burghead Bulls are a group of carved Pictish stones from the site of Burghead Fort in Moray, Scotland, each featuring an incised image of a bull. Up to 30 were discovered during the demolition of the fort to create the town of Burghead in the 19th century, but most were lost when they were used to build the harbour quayside. Six remain: two in the Visitor Centre in Burghead, two in Elgin Museum, one in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, and one in the British Museum in London.

Green Castle is a naturally defended rocky outcrop in the village of Portknockie in Moray, Scotland, that was occupied successively by small promontory forts of the Iron Age and Pictish periods.

The Knock of Alves is a small wooded hill that lies 3 miles (4.8 km) to the west of Elgin in Moray, Scotland, rising to 335 feet (102 m) above ordnance datum. Its summit is marked by York Tower, a 3-storey octagonal folly erected in 1827 to commemorate Prince Frederick, the Duke of York; and the Forteath Mausoleum, built in 1850 as the burial place of 7 members of the Forteath family of the nearby house of Newton.

Dunnicaer, or Dun-na-caer, is a precipitous sea stack just off the coast of Aberdeenshire, Scotland, between Dunnottar Castle and Stonehaven. Despite the unusual difficulty of access, in 1832 Pictish symbol stones were found on the summit and 21st-century archaeology has discovered evidence of a Pictish hill fort which may have incorporated the stones in its structure. The stones may have been incised in the third or fourth centuries AD but this goes against the general archaeological view that the simplest and earliest symbol stones date from the fifth or even seventh century AD.

The Sculptor's Cave is a sandstone cave on the south shore of the Moray Firth in Scotland, near the small settlement of Covesea, between Burghead and Lossiemouth in Moray. It is named after the Pictish carvings incised on the walls of the cave near its entrances. There are seven groups of carvings dating from the 6th or 7th century, including fish, crescent and V-rod, pentacle, triple oval, step, rectangle, disc and rectangle, flower, and mirror patterns, some very basic but others more sophisticated.

Scotland in the Iron Age concerns the period of prehistory in Scotland from about 800 BCE to the commencement of written records in the early Christian era. As the Iron Age emerged from the preceding Bronze Age, it becomes legitimate to talk of a Celtic culture in Scotland. It was an age of forts and farmsteads, the most dramatic remains of which are brochs some of whose walls still exceed 6.5 m (21 ft) in height. Pastoral farming was widespread but as the era progressed there is more evidence of cereal growing and increasing intensification of agriculture. Unlike the previous epochs of human occupation, early Iron Age burial sites in Scotland are relatively rare although monasteries and other religious sites were constructed in the last centuries of the period. The Stirling torcs are amongst examples of high quality crafts produced at an early date and the Pictish symbol stones are emblematic of later times.