Related Research Articles

Count Sámuel Teleki de Szék was a Hungarian explorer who led the first expedition to Northern Kenya. He was the first European to see Lake Rudolf, though the existence of the lake was well known both in Africa and Europe before Teleki conceived of the expedition.

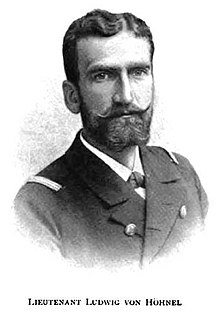

Ludwig Ritter von Höhnel was an Austrian naval officer and explorer. He was trained at the naval academy in Fiume, then part of the Austrian empire. His brother was the naturalist Franz Xaver Rudolf von Höhnel (1852–1920).

The Yaaku, are a people who are said to have lived in regions of southern Ethiopia and central Kenya, possibly through to the 18th century. The language they spoke is today called Yaakunte. The Yaaku assimilated a hunter-gathering population, whom they called Mukogodo, when they first settled in their place of origin and the Mukogodo adopted the Yaakunte language. However, the Yaaku were later assimilated by a food producing population and they lost their way of life. The Yaakunte language was kept alive for sometime by the Mukogodo who maintained their own hunter-gathering way of life, but they were later immersed in Maasai culture and adopted the Maa language and way of life. The Yaakunte language is today facing extinction but is undergoing a revival movement. In the present time, the terms Yaaku and Mukogodo, are used to refer to a population living in Mukogodo forest west of Mount Kenya.

The Turkana are a Nilotic people native to the Turkana County in northwest Kenya, a semi-arid climate region bordering Lake Turkana in the east, Pokot, Rendille and Samburu people to the south, Uganda to the west, and South Sudan and Ethiopia to the north. They refer to their land as Turkan.

The Rendille are a Cushitic-speaking ethnic group inhabiting the northern Eastern Province of Kenya.

Ateker, or ŋaTekerin, is a common name for the closely related Jie, Karamojong, Turkana, Toposa, Nyangatom and Teso peoples and their languages. These ethnic groups inhabit an area across Uganda and Kenya. Itung'a and Teso have been used among ethnographers, while the term Teso-Turkana is sometimes used for the languages, which are of Eastern Nilotic stock. Ateker means 'clan' or 'tribe' in the Teso language. In the Lango language, the word for clan is atekere.

The Kwavi people were a community commonly spoken of in the folklore of a number of Kenyan and Tanzanian communities that inhabited regions of south-central Kenya and north-central Tanzania at various points in history. The conflicts between the Uasin Gishu/Masai and Kwavi form much of the literature of what are now known as the Iloikop wars.

The Kalenjin people are an ethnolinguistic group indigenous to East Africa, with a presence, as dated by archaeology and linguistics, that goes back many centuries. Their history is therefore deeply interwoven with those of their neighboring communities as well as with the histories of Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, South Sudan, and Ethiopia.

The Lumbwa were a pastoral community which inhabited southern Kenya and northern Tanzania. The term Lumbwa has variously referred to a Kalenjin-speaking community, portions of the Maa-speaking Loikop communities since the mid-19th century, and to the Kalenjin-speaking Kipsigis community for much of the late 19th to mid-20th centuries.

The Loikop people, also known as Wakuafi, Kor, Mu-Oko, Muoko/Ma-Uoko and Mwoko, were a tribal confederacy who inhabited present-day Kenya in the regions north and west of Mount Kenya and east and south of Lake Turkana. The area is roughly conterminous with Samburu and Laikipia Counties and portions of Baringo, Turkana and (possibly) Meru Counties. The group spoke a common tongue related to the Maasai language, and typically herded cattle. The Loikop occasionally interacted with the Cushitic, Bantu, and Chok peoples. The confederacy had dispersed by the 21st century.

The Chok were a society that lived on the Elgeyo Escarpment in Kenya.

The Aoyate drought was an acute meteorological drought that according to Turkana tradition affected much of the Rift Valley region of Kenya during the late 18th century or early 19th century.

Mutai is a term used by the Maa-speaking communities of Kenya to describe a period of wars, usually triggered by disease and/or drought affecting widespread areas of the Rift Valley region of Kenya. According to Samburu and Maasai tradition, two periods of Mutai occurred during the nineteenth century. The second Mutai lasted from the 1870s to the 1890s.

The Iloikop wars were a series of wars between the Maasai and a community referred to as Kwavi and later between Maasai and alliance of reformed Kwavi communities. These were pastoral communities that occupied large tracts of East Africa's savanna's during the late 18th and 19th centuries. These wars occurred between c.1830 and 1880.

Mutai is a term used by the Maa-speaking communities of Kenya to describe a period of wars, usually triggered by disease and/or drought and affecting widespread areas of the Rift Valley region of Kenya. According to Samburu and Maasai folklore, periods of Mutai occurred during the nineteenth century.

The Chemwal people were a Kalenjin-speaking society that inhabited regions of western and north-western Kenya as well as the regions around Mount Elgon at various times through to the late 19th century. The Nandi word Sekker was used by Pokot elders to describe one section of a community that occupied the Elgeyo escarpment and whose territory stretched across the Uasin Gishu plateau. This section of the community appears to have neighbored the Karamojong who referred to them as Siger, a name that derived from the Karimojong word esigirait. The most notable element of Sekker/Chemwal culture appears to have been a dangling adornment of a single cowrie shell attached to the forelock of Sekker women, at least as of the late 1700s and early 1800s.

The Uasin Gishu people were a community that inhabited a plateau located in western Kenya that today bears their name. They are said to have arisen from the scattering of the Kwavi by the Maasai in the 1830s. They were one of two significant sections of that community that stayed together. The other being the Laikipiak with whom they would later ally against the Maasai.

The Ngaa people were a community that according to the traditions of many Kenyan communities inhabited regions of the Swahili coast and the Kenyan hinterland at various times in history.

The Murutu people were a community that, according to the oral literature of the Meru people of Kenya, inhabited regions of the Swahili coast and the Kenyan hinterland at various times in history.

The Laikipiak people were a community that inhabited the plateau located on the eastern escarpment of the Rift Valley in Kenya that today bears their name. They are said to have arisen from the scattering of the Kwavi by the Maasai in the 1830s.They were one of two significant sections of that community that stayed together. The other being the Uasin Gishu with whom they would later ally against the Maasai. Many Maa-speakers in Laikipia County today claim Laikipiak ancestry, namely those among the Ilng'wesi, Ildigirri and Ilmumonyot sub-sections of the Laikipia Maasai.

References

- ↑ Stigand, Chauncy (1913). The land of Zinj, being an account of British East Africa, its ancient history and present inhabitants. London: Constable & Company ltd. p. 286.

- 1 2 Höhnel, Ritter von (1894). Discovery of lakes Rudolf and Stefanie; a narrative of Count Samuel Teleki's exploring & hunting expedition in eastern equatorial Africa in 1887 & 1888. London: Longmans, Green and Co. p. 234–237.

- 1 2 3 Fadiman, J. (1994). When We Began There Were Witchmen. California: University of California Press. pp. 83–84. ISBN 9780520086159.

- ↑ Straight, Bilinda; Lane, Paul; Hilton, Charles (2016). ""Dust people": Samburu perspectives on disaster, identity, and landscape". Journal of Eastern African Studies. 10 (1): 179. doi:10.1080/17531055.2016.1138638. S2CID 147620799.

- 1 2 Lamphear, John (1988). "The People of the Grey Bull: The Origin and Expansion of the Turkana". The Journal of African History. 29 (1): 30. doi:10.1017/S0021853700035970. JSTOR 182237.

- ↑ MacDonald, J.R.L (1899). "Notes on the Ethnology of Tribes Met with During Progress of the Juba Expedition of 1897-99". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 29 (3/4): 240. doi:10.2307/2843005. JSTOR 2843005.

- ↑ MacDonald, J.R.L (1899). "Notes on the Ethnology of Tribes Met with During Progress of the Juba Expedition of 1897-99". The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 29 (3/4): 240. doi:10.2307/2843005. JSTOR 2843005.

- ↑ Arkell-Hardwick, Alfred (1903). An Ivory Trader in North Kenia: The Record of an Expedition Through Kikuyu to Galla-land in East Equatorial Africa. London: Longmans, Green, and co. p. 241.

- ↑ Arkell-Hardwick, Alfred (1903). An Ivory Trader in North Kenia: The Record of an Expedition Through Kikuyu to Galla-land in East Equatorial Africa. London: Longmans, Green, and co. p. 221.

- ↑ Arkell-Hardwick, Alfred (1903). An Ivory Trader in North Kenia: The Record of an Expedition Through Kikuyu to Galla-land in East Equatorial Africa. London: Longmans, Green, and co. p. 222.

- ↑ Arkell-Hardwick, Alfred (1903). An Ivory Trader in North Kenia: The Record of an Expedition Through Kikuyu to Galla-land in East Equatorial Africa. London: Longmans, Green, and co. p. 223.