Byblos, also known as Jebeil, Jbeil or Jubayl, is an ancient city in the Keserwan-Jbeil Governorate of Lebanon. The area is believed to have been first settled between 8800 and 7000 BC and continuously inhabited since 5000 BC. During its history, Byblos was part of numerous cultures including Egyptian, Phoenician, Assyrian, Persian, Hellenistic, Roman, Genoese, Mamluk and Ottoman. Urbanisation is thought to have begun during the third millennium BC and it developed into a city making it one of the oldest cities in the world. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The sarcophagus ofEshmunazar II is a 6th-century BC sarcophagus unearthed in 1855 in the grounds of an ancient necropolis southeast of the city of Sidon, in modern-day Lebanon, that contained the body of Eshmunazar II, Phoenician King of Sidon. One of only three Ancient Egyptian sarcophagi found outside Egypt, with the other two belonging to Eshmunazar's father King Tabnit and to a woman, possibly Eshmunazar's mother Queen Amoashtart, it was likely carved in Egypt from local amphibolite, and captured as booty by the Sidonians during their participation in Cambyses II's conquest of Egypt in 525 BC. The sarcophagus has two sets of Phoenician inscriptions, one on its lid and a partial copy of it on the sarcophagus trough, around the curvature of the head. The lid inscription was of great significance upon its discovery as it was the first Phoenician language inscription to be discovered in Phoenicia proper and the most detailed Phoenician text ever found anywhere up to that point, and is today the second longest extant Phoenician inscription, after the Karatepe bilingual.

Jean Pierre Marie Montet was a French Egyptologist.

The Byblos script, also known as the Byblos syllabary, Pseudo-hieroglyphic script, Proto-Byblian, Proto-Byblic, or Byblic, is an undeciphered writing system, known from ten inscriptions found in Byblos, a coastal city in Lebanon. The inscriptions are engraved on bronze plates and spatulas, and carved in stone. They were excavated by Maurice Dunand, from 1928 to 1932, and published in 1945 in his monograph Byblia Grammata. The inscriptions are conventionally dated to the second millennium BC, probably between the 18th and 15th centuries BC.

The Ahiram sarcophagus was the sarcophagus of a Phoenician King of Byblos, discovered in 1923 by the French excavator Pierre Montet in tomb V of the royal necropolis of Byblos.

René Dussaud was a French Orientalist, archaeologist, and epigrapher. Among his major works are studies on the religion of the Hittites, the Hurrians, the Phoenicians and the Syriacs. He became curator of the Department of Near Eastern Antiquities at the Louvre Museum and a member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. One notable student was pioneering Jewish archaeologist Judith Marquet-Krause.

Bodashtart was a Phoenician ruler, who reigned as King of Sidon, the grandson of King Eshmunazar I, and a vassal of the Achaemenid Empire. He succeeded his cousin Eshmunazar II to the throne of Sidon, and scholars believe that he was succeeded by his son and proclaimed heir Yatonmilk.

The Byblian royal inscriptions are five inscriptions from Byblos written in an early type of Phoenician script, in the order of some of the kings of Byblos, all of which were discovered in the early 20th century.

The Temple of Baalat Gebal was an important Bronze Age temple structure in the World Heritage Site of Byblos. The temple was dedicated to Ba'alat Gebal, the goddess of the city of Byblos, known later to the Greeks as Atargatis. Built in 2800 BCE, it was the largest and most important sanctuary in ancient Byblos, and is considered to be "one of the first monumental structures of the Syro-Palestinian region". Two centuries after the construction of the Temple of Baalat Gebal, the Temple of the Obelisks was built approximately 100m to the east.

The Osorkon Bust, also known as the Eliba'l Inscription is a bust of Egyptian pharaoh Osorkon I, discovered in Byblos in the 19th century. Like the Tabnit sarcophagus from Sidon, it is decorated with two separate and unrelated inscriptions – one in Egyptian hieroglyphics and one in Phoenician script. It was created in the early 10th century BC, and was unearthed c. 1881, very likely in the Temple of Baalat Gebal.

The Yehawmilk stele, de Clercq stele, or Byblos stele, also known as KAI 10 and CIS I 1, is a Phoenician inscription from c.450 BC found in Byblos at the end of Ernest Renan's Mission de Phénicie. Yehawmilk, king of Byblos, dedicated the stele to the city’s protective goddess Ba'alat Gebal.

The Abydos graffiti is Phoenician and Aramaic graffiti found on the walls of the Temple of Seti I at Abydos, Egypt. The inscriptions are known as KAI 49, CIS I 99-110 and RES 1302ff.

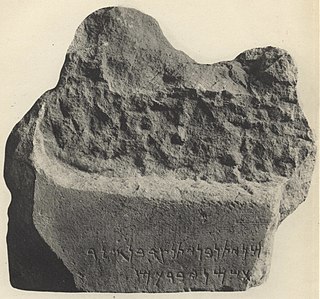

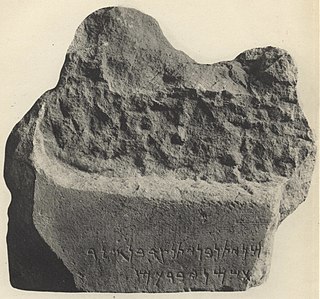

The Byblos Necropolis graffito is a Phoenician inscription situated in the Royal necropolis of Byblos.

The royal necropolis of Byblos is a group of nine Bronze Age underground shaft and chamber tombs housing the sarcophagi of several kings of the city. Byblos is a coastal city in Lebanon, and one of the oldest continuously populated cities in the world. The city established major trade links with Egypt during the Bronze Age, resulting in a heavy Egyptian influence on local culture and funerary practices. The location of ancient Byblos was lost to history, but was rediscovered in the late 19th century by the French biblical scholar and Orientalist Ernest Renan. The remains of the ancient city sat on top of a hill in the immediate vicinity of the modern city of Jbeil. Exploratory trenches and minor digs were undertaken by the French mandate authorities, during which reliefs inscribed with Egyptian hieroglyphs were excavated. The discovery stirred the interest of western scholars, leading to systematic surveys of the site.

The Abibaʻl Inscription is a Phoenician inscription from Byblos on the base of a throne on which a statue of Sheshonq I was placed. It is held at the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin.

The Yehimilk inscription is a Phoenician inscription published in 1930, currently in the museum of Byblos Castle.

The Batnoam inscription is a Phoenician inscription on a sarcophagus. It is dated to c. 450-425 BCE.

The Byblos bronze spatulas are a number bronze spatulas found in Byblos, two of which were inscribed. One contains a Phoenician inscription and one contains an inscription in the Byblos syllabary.

The Phoenician Adoration steles are a number of Phoenician and Punic steles depicting the adoration gesture (orans).

The Eshmun inscription is a Phoenician inscription on a fragment of grey-blue limestone found at the Temple of Eshmun in 1901. It is also known as RES 297. Some elements of the writing have been said to be similar to the Athenian Greek-Phoenician inscriptions. Today, it is held in the Museum of the Ancient Orient in Istanbul.