Alice Stone Blackwell was an American feminist, suffragist, journalist, radical socialist, and human rights advocate.

The Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage was an American organization formed in 1913 led by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns to campaign for a constitutional amendment guaranteeing women's suffrage. It was inspired by the United Kingdom's suffragette movement, which Paul and Burns had taken part in. Their continuous campaigning drew attention from congressmen, and in 1914 they were successful in forcing the amendment onto the floor for the first time in decades.

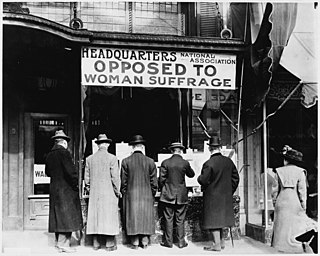

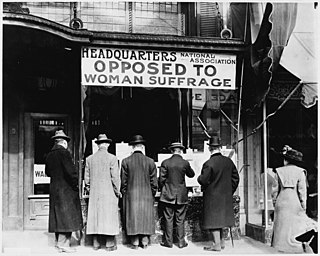

Anti-suffragism was a political movement composed of both men and women that began in the late 19th century in order to campaign against women's suffrage in countries such as Australia, Canada, Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States. To some extent, Anti-suffragism was a Classical Conservative movement that sought to keep the status quo for women. More American women organized against their own right to vote than in favor of it, until 1916. Anti-suffragism was associated with "domestic feminism," the belief that women had the right to complete freedom within the home. In the United States, these activists were often referred to as "remonstrants" or "antis."

Pattie Ruffner Jacobs was an American suffragist from Birmingham, Alabama. She was inducted into the Alabama Women's Hall of Fame in 1978.

Grace Belden Wilbur Trout was an American suffragist who was president of two prominent Illinois suffrage organizations, the Chicago Political Equality League and the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association (IESA). She was instrumental in getting the Illinois legislature to pass the presidential and municipal suffrage law, also known as the "Illinois Law," a law giving women partial suffrage by allowing them to vote in local and national elections. Though inexperienced with legislative work, she implemented a strategic lobbying plan in the state legislature that succeeded. She also organized public campaigns to build support for suffrage and secured favorable statewide media coverage.

Nina Evans Allender was an American artist, cartoonist, and women's rights activist. She studied art in the United States and Europe with William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri. Allender worked as an organizer, speaker, and campaigner for women's suffrage and was the "official cartoonist" for the National Woman's Party's publications, creating what became known as the "Allender Girl."

This timeline highlights milestones in women's suffrage in the United States, particularly the right of women to vote in elections at federal and state levels.

Women's suffrage was established in the United States on a full or partial basis by various towns, counties, states, and territories during the latter decades of the 19th century and early part of the 20th century. As women received the right to vote in some places, they began running for public office and gaining positions as school board members, county clerks, state legislators, judges, and, in the case of Jeannette Rankin, as a member of Congress.

The Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association (MWSA) was an American organization devoted to women's suffrage in Massachusetts. It was active from 1870 to 1919.

The Boston Equal Suffrage Association for Good Government (BESAGG) was an American organization devoted to women's suffrage in Massachusetts. It was active from 1901 to 1920. Like the College Equal Suffrage League, it attracted younger, less risk-averse members than some of the more established organizations. BESAGG played an important role in the ratification of the 19th amendment in Massachusetts. After 1920, it became the Boston League of Women Voters.

The Texas Equal Suffrage Association (TESA) was an organization founded in 1903 to support white women's suffrage in Texas. It was originally formed under the name of the Texas Woman Suffrage Association (TWSA) and later renamed in 1916. TESA did allow men to join. TESA did not allow black women as members, because at the time to do so would have been "political suicide." The El Paso Colored Woman's Club applied for TESA membership in 1918, but the issue was deflected and ended up going nowhere. TESA focused most of their efforts on securing the passage of the federal amendment for women's right to vote. The organization also became the state chapter of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). After women earned the right to vote, TESA reformed as the Texas League of Women Voters.

The National Association Opposed to Women Suffrage (NAOWS) was founded in the United States by women opposed to the suffrage movement in 1911. It was the most popular anti-suffrage organization in northeastern cities. NAOWS had influential local chapters in many states, including Texas and Virginia.

Minnie Bronson was an American anti-suffragist activist who was general secretary of the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage.

Oreola Williams Haskell was an American activist for suffrage, author, and poet in the early twentieth century.

Women's suffrage was granted in Virginia in 1920, with the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The General Assembly, Virginia's governing legislative body, did not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until 1952. The argument for women's suffrage in Virginia began in 1870, but it did not gain traction until 1909 with the founding of the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia. Between 1912 and 1916, Virginia's suffragists would bring the issue of women's voting rights to the floor of the General Assembly three times, petitioning for an amendment to the state constitution giving women the right to vote; they were defeated each time. During this period, the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia and its fellow Virginia suffragists fought against a strong anti-suffragist movement that tapped into conservative, post-Civil War values on the role of women, as well as racial fears. After achieving suffrage in August 1920, over 13,000 women registered within one month to vote for the first time in the 1920 United States presidential election.

The women's suffrage movement began in California in the 19th century and was successful with the passage of Proposition 4 on October 10, 1911. Many of the women and men involved in this movement remained politically active in the national suffrage movement with organizations such as the National American Women's Suffrage Association and the National Woman's Party.

Harriet Taylor Treadwell, also seen as Harriette Taylor Treadwell, was an American suffragist and educator.

The first women's suffrage effort in Florida was led by Ella C. Chamberlain in the early 1890s. Chamberlain began writing a women's suffrage news column, started a mixed-gender women's suffrage group and organized conventions in Florida.

Grace Allen Johnson was an American suffragist, educator, and peace activist known for her leadership in the women's suffrage movement in Massachusetts. Initially holding traditional views on women's roles, she became actively involved in suffrage after attending a meeting in Cambridge, England, in 1907. Johnson was the founder and president of the Cambridge Political Equality Association (CPEA), rallying public support for women's suffrage. She later focused on international peace activism and played a key role in introducing proportional representation in Cambridge in 1940.

The Illinois Association Opposed to the Extension of Suffrage to Women (IAOESW) was an influential organization in the state of Illinois that actively campaigned against the extension of voting rights to women. Founded in 1897 by Caroline Fairfield Corbin, the association played a significant role in the anti-suffrage movement in the United States.