An image is an artifact that depicts visual perception, such as a photograph or other two-dimensional picture, that resembles a subject—usually a physical object—and thus provides a depiction of it. In the context of signal processing, an image is a distributed amplitude of color(s).

The avant-garde are people or works that are experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society. It may be characterized by nontraditional, aesthetic innovation and initial unacceptability, and it may offer a critique of the relationship between producer and consumer.

Postmodern art is a body of art movements that sought to contradict some aspects of modernism or some aspects that emerged or developed in its aftermath. In general, movements such as intermedia, installation art, conceptual art and multimedia, particularly involving video are described as postmodern.

Pictorialism is an international style and aesthetic movement that dominated photography during the later 19th and early 20th centuries. There is no standard definition of the term, but in general it refers to a style in which the photographer has somehow manipulated what would otherwise be a straightforward photograph as a means of "creating" an image rather than simply recording it. Typically, a pictorial photograph appears to lack a sharp focus, is printed in one or more colors other than black-and-white and may have visible brush strokes or other manipulation of the surface. For the pictorialist, a photograph, like a painting, drawing or engraving, was a way of projecting an emotional intent into the viewer's realm of imagination.

Alfred Stieglitz was an American photographer and modern art promoter who was instrumental over his fifty-year career in making photography an accepted art form. In addition to his photography, Stieglitz was known for the New York art galleries that he ran in the early part of the 20th century, where he introduced many avant-garde European artists to the U.S. He was married to painter Georgia O'Keeffe.

Pure photography or straight photography refers to photography that attempts to depict a scene or subject in sharp focus and detail, in accordance with the qualities that distinguish photography from other visual media, particularly painting. Originating as early as 1904, the term was used by critic Sadakichi Hartmann in the magazine Camera Work, and later promoted by its editor, Alfred Stieglitz, as a more pure form of photography than Pictorialism. Once popularized by Stieglitz and other notable photographers, such as Paul Strand, it later became a hallmark of Western photographers, such as Edward Weston, Ansel Adams and others.

Visual anthropology is a subfield of social anthropology that is concerned, in part, with the study and production of ethnographic photography, film and, since the mid-1990s, new media. More recently it has been used by historians of science and visual culture. Although sometimes wrongly conflated with ethnographic film, Visual Anthropology encompasses much more, including the anthropological study of all visual representations such as dance and other kinds of performance, museums and archiving, all visual arts, and the production and reception of mass media. Histories and analyses of representations from many cultures are part of Visual Anthropology: research topics include sandpaintings, tattoos, sculptures and reliefs, cave paintings, scrimshaw, jewelry, hieroglyphics, paintings and photographs. Also within the province of the subfield are studies of human vision, properties of media, the relationship of visual form and function, and applied, collaborative uses of visual representations. Multimodal anthropology describes the latest turn in the subfield, which considers how emerging technologies like immersive virtual reality, augmented reality, mobile apps, social networking, gaming along with film, photography and art is reshaping anthropological research, practice and teaching.

A tableau vivant, French for 'living picture', is a static scene containing one or more actors or models. They are stationary and silent, usually in costume, carefully posed, with props and/or scenery, and may be theatrically lit. It thus combines aspects of theatre and the visual arts.

Literary modernism, or modernist literature, has its origins in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, mainly in Europe and North America, and is characterized by a very self-conscious break with traditional ways of writing, in both poetry and prose fiction. Modernists experimented with literary form and expression, as exemplified by Ezra Pound's maxim to "Make it new." This literary movement was driven by a conscious desire to overturn traditional modes of representation and express the new sensibilities of their time. The horrors of the First World War saw the prevailing assumptions about society reassessed.

American modernism, much like the modernism movement in general, is a trend of philosophical thought arising from the widespread changes in culture and society in the age of modernity. American modernism is an artistic and cultural movement in the United States beginning at the turn of the 20th century, with a core period between World War I and World War II. Like its European counterpart, American modernism stemmed from a rejection of Enlightenment thinking, seeking to better represent reality in a new, more industrialized world.

Postmodernist film is a classification for works that articulate the themes and ideas of postmodernism through the medium of cinema. Postmodernist film attempts to subvert the mainstream conventions of narrative structure and characterization, and tests the audience's suspension of disbelief. Typically, such films also break down the cultural divide between high and low art and often upend typical portrayals of gender, race, class, genre, and time with the goal of creating something that does not abide by traditional narrative expression.

Charles Henry Caffin was an Anglo-American writer and art critic, born in Sittingbourne, Kent, England. After graduating from Magdalen College, Oxford, in 1876, with a broad background in culture and aesthetics, he engaged in scholastic and theatrical work. In 1888, he married Caroline Scurfield, a British actress and writer. They had two children, daughters Donna and Freda Caffin. In 1892, he moved to the United States. He worked in the decoration department of the Chicago Exposition, and after moving to New York City in 1897, he was the art critic of Harper's Weekly, the New York Evening Post, the New York Sun (1901–04), the International Studio, and the New York American. His publications are of a popular rather than a scholarly character, but he was an important early if equivocal advocate of modern art in America. His writings were suggestive and stimulating to laymen and encouraged interest in many fields of art. One of his last books, Art for Life's Sake (1913), described his philosophy, which argued that the arts must be seen as "an integral part of life....[not] an orchid-like parasite on life" or a specialized or elite indulgence. He also argued strenuously for art education in American elementary schools and high schools and was a frequent lecturer.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to photography:

In the visual arts, late modernism encompasses the overall production of most recent art made between the aftermath of World War II and the early years of the 21st century. The terminology often points to similarities between late modernism and post-modernism although there are differences. The predominant term for art produced since the 1950s is contemporary art. Not all art labelled as contemporary art is modernist or post-modern, and the broader term encompasses both artists who continue to work in modern and late modernist traditions, as well as artists who reject modernism for post-modernism or other reasons. Arthur Danto argues explicitly in After the End of Art that contemporaneity was the broader term, and that postmodern objects represent a subsector of the contemporary movement which replaced modernity and modernism, while other notable critics: Hilton Kramer, Robert C. Morgan, Kirk Varnedoe, Jean-François Lyotard and others have argued that postmodern objects are at best relative to modernist works.

291 was an arts and literary magazine that was published from 1915 to 1916 in New York City. It was created and published by a group of four individuals: photographer/modern art promoter Alfred Stieglitz, artist Marius de Zayas, art collector/journalist/poet Agnes E. Meyer and photographer/critic/arts patron Paul Haviland. Initially intended as a way to bring attention to Stieglitz's gallery of the same name (291), it soon became a work of art in itself. The magazine published original art work, essays, poems and commentaries by Francis Picabia, John Marin, Max Jacob, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, de Zayas, Stieglitz and other avant-garde artists and writers of the time, and it is credited with being the publication that introduced visual poetry to the United States.

The Steerage is a photograph taken by Alfred Stieglitz in 1907. It has been hailed as one of the greatest photographs of all time because it captures in a single image both a formative document of its time and one of the first works of artistic modernism.

Al Filreis is the Kelly Professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania, Faculty Director of the Kelly Writers House, and Director of the Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing at the University of Pennsylvania. With Charles Bernstein, he founded PennSound in 2003; PennSound is a large archive of recordings of poets reading their own poetry. Filreis is also publisher of Jacket2 magazine and host of a monthly podcast series called "PoemTalk", a collaboration with the Poetry Foundation. Among his books are Stevens and the Actual World, Modernism from Right to Left, and Counter-revolution of the Word: The Conservative Attack on Modern Poetry, 1945-1960.

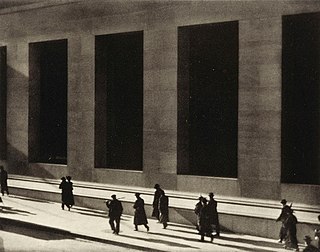

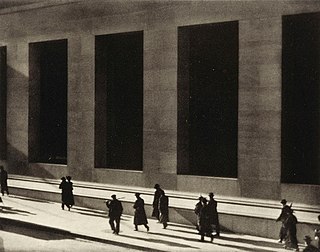

Wall Street is a platinum palladium print photograph by the American photographer Paul Strand taken in 1915. There are currently only two vintage prints of this photograph with one at the Whitney Museum of American Art and the other, along with negatives, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. This photograph was included in Paul Strand, circa 1916, an exhibition of photographs that exemplify his push toward modernism.

For other people named Bob Brown, see Bob Brown (disambiguation)