Related Research Articles

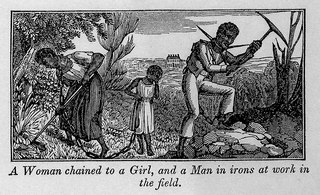

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Passage. Europeans established a coastal slave trade in the 15th century and trade to the Americas began in the 16th century, lasting through the 19th century. The vast majority of those who were transported in the transatlantic slave trade were from Central Africa and West Africa and had been sold by West African slave traders to European slave traders, while others had been captured directly by the slave traders in coastal raids. European slave traders gathered and imprisoned the enslaved at forts on the African coast and then brought them to the Americas. Except for the Portuguese, European slave traders generally did not participate in the raids because life expectancy for Europeans in sub-Saharan Africa was less than one year during the period of the slave trade. Portuguese coastal raiders found that slave raiding was too costly and often ineffective and opted for established commercial relations.

The Middle Passage was the stage of the Atlantic slave trade in which millions of enslaved Africans were transported to the Americas as part of the triangular slave trade. Ships departed Europe for African markets with manufactured goods, which were then traded for slaves with rulers of African states and other African slave traders. Slave ships transported the slaves across the Atlantic. The proceeds from selling slaves were then used to buy products such as furs and hides, tobacco, sugar, rum, and raw materials, which would be transported back to Europe to complete the triangle.

The slave codes were laws relating to slavery and enslaved people, specifically regarding the Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery in the Americas.

The Barbados Slave Code of 1661, officially titled as An Act for the better ordering and governing of Negroes, was a law passed by the Parliament of Barbados to provide a legal basis for slavery in the English colony of Barbados. It is the first comprehensive Slave Act, and the code's preamble, which stated that the law's purpose was to "protect them [slaves] as we do men's other goods and Chattels", established that black slaves would be treated as chattel property in the island's court.

The Slave Coast is a historical name formerly used for that part of coastal West Africa along the Bight of Biafra and the Bight of Benin that is located between the Volta River and the Lagos Lagoon. The name is derived from the region's history as a major source of African people sold into slavery during the Atlantic slave trade from the early 16th century to the late 19th century.

Elmina Castle was erected by the Portuguese in 1482 as Castelo de São Jorge da Mina, also known as Castelo da Mina or simply Mina, in present-day Elmina, Ghana, formerly the Gold Coast. It was the first trading post built on the Gulf of Guinea, and the oldest European building in existence south of the Sahara.

The Dutch Gold Coast or Dutch Guinea, officially Dutch possessions on the Coast of Guinea was a portion of contemporary Ghana that was gradually colonized by the Dutch, beginning in 1612. The Dutch began trading in the area around 1598, joining the Portuguese which had a trading post there since the late 1400s. Eventually, the Dutch Gold Coast became the most important Dutch colony in West Africa after Fort Elmina was captured from the Portuguese in 1637, but fell into disarray after the abolition of the slave trade in the early 19th century. On 6 April 1872, the Dutch Gold Coast was, in accordance with the Anglo-Dutch Treaties of 1870–71, ceded to the United Kingdom.

Slavery has historically been widespread in Africa. Systems of servitude and slavery were once commonplace in parts of Africa, as they were in much of the rest of the ancient and medieval world. When the trans-Saharan slave trade, Red Sea slave trade, Indian Ocean slave trade and Atlantic slave trade began, many of the pre-existing local African slave systems began supplying captives for slave markets outside Africa. Slavery in contemporary Africa is still practised despite it being illegal.

A barracoon is a type of barracks used historically for the internment of enslaved or criminal human beings.

The Dutch Slave Coast refers to the trading posts of the Dutch West India Company on the Slave Coast, which lie in contemporary Ghana, Benin, Togo, and Nigeria. The primary purpose of the trading post was to supply slaves for the Dutch colonies in the Americas. Dutch involvement on the Slave Coast started with the establishment of a trading post in Offra in 1660. Later, trade shifted to Ouidah, where the English and French also had a trading post. Political unrest caused the Dutch to abandon their trading post at Ouidah in 1725, now moving to Jaquim, at which place they built Fort Zeelandia. By 1760, the Dutch had abandoned their last trading post in the region.

The Danish slave trade occurred separately in two different periods: the trade in European slaves during the Viking Age, from the 8th to 10th century; and the Danish role in selling African slaves during the Atlantic slave trade, which commenced in 1733 and ended in 1807 when the abolition of slavery was announced. The location of the latter slave trade primarily occurred in the Danish West Indies where slaves were tasked with many different manual labour activities, primarily working on sugar plantations. The slave trade had many impacts that varied in their nature, with some more severe than others. After many years of slavery in the Danish West Indies, Christian VII decided to abolish slave trading.

Panyarring was the practice of seizing and holding persons until the repayment of debt or resolution of a dispute which became a common activity along the Atlantic coast of Africa in the 18th and 19th centuries. The practice developed from pawnship, a common practice in West Africa where members of a family borrowing money would be pledged as collateral to the family providing credit until the repayment of the debt. Panyarring though is different from this practice as it involves the forced seizure of persons when a debt was not repaid.

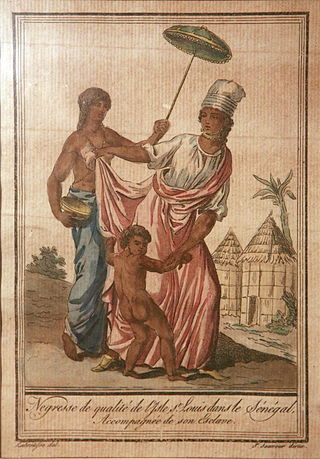

Signares were black and mulatto Senegalese women who had an influence via their marriage with European men and their patrimony. These women of color managed to gain some individual assets, status, and power in the hierarchies of the Atlantic slave trade.

Henry Hawley was the English Governor of Barbados from 1630 to 1639/40.

Betsy Heard was a Euro‐African slave trader and merchant.

Gold Coast Euro-Africans were a historical demographic based in coastal urban settlements in colonial Ghana, that arose from unions between European men and African women from the late 15th century – the decade between 1471 and 1482, until the mid-20th century, circa 1957, when Ghana attained its independence. In this period, different geographic areas of the Gold Coast were politically controlled at various times by the Portuguese, Germans, Swedes, Danes, Dutch and the British. There are also records of merchants of other European nationalities such as the Spaniards, French, Italians and Irish, operating along the coast, in addition to American sailors and traders from New York, Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Euro-Africans were influential in intellectual, technocratic, artisanal, commercial and public life in general, actively participating in multiple fields of scholarly and civic importance. Scholars have referred to this Euro-African population of the Gold Coast as "mulattos", "mulatofoi" and "owulai" among other descriptions. The term, owula conveys contemporary notions of "gentlemanliness, learning and urbanity" or "a salaried big man" in the Ga language. The cross-cultural interactions between Europeans and Africans were mercantile-driven and an avenue to boost social capital for economic and political gain i.e. "wealth and power". The growth and development of Christianity during the colonial period also instituted motifs of modernity vis-à-vis Euro-African identity. This model created a spectrum of practices, ranging from a full celebration of native African customs to a total embrace and acculturation of European culture.

Slave marriages in the United States were typically illegal before the American Civil War abolished slavery in the US. Enslaved African Americans were legally considered chattel, and they were denied civil and political rights until the United States abolished slavery with the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Both state and federal laws denied, or rarely defined, rights for enslaved people.

Thomas Foxcroft (1733–1809) was an English slave trader. He was responsible for at least 91 slave voyages in the years between 1759 and 1792. A contemporary set of financial accounts for one slave voyage by his slave-ship Bloom has been preserved. Captain Robert Bostock, Bloom's master, bought 349 enslaved people in Africa; 42 captives died and 307 captives were sold in the West Indies for £9858. The net profit on the voyage to the owners amounted to £8,123 7s 2d, or £26 9s 2d per captive sold.

Hope (Esperança) Booker was a Gambian woman.

Marie Baude (1703-?) was a Senegambian woman who was married to convicted murderer, Jean Pinet. Despite a lack of significant evidence regarding her life, Baude's narrative embodies the intricate dynamics of the transatlantic slave trade era, from her ascent as a signare, wielding influence amid the trade, to the events surrounding her husband's trial and deportation.

References

- ↑ Pernille Ipsen (2013). ""The Christened Mulatresses": Euro-African Families in a Slave-Trading Town". The William and Mary Quarterly. 70 (2): 371–398. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.70.2.0371. JSTOR 10.5309/willmaryquar.70.2.0371.

- ↑ "Ghana - Arrival of the Europeans". countrystudies.us. Archived from the original on 2016-11-03. Retrieved 2018-12-22.

- ↑ Ipsen, Pernille (2015). Daughters of the Trade: Atlantic Slavers and Interracial Marriage on the Gold Coast. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 1, 21, 31. ISBN 978-0-8122-4673-5.

- 1 2 3 Ipsen, Pernille (2015). Daughters of the Trade: Atlantic Slavers and Interracial Marriage on the Gold Coast. ISBN 978-0-8122-4673-5. pp. 9.

- ↑ George E. Brooks, Eurafricans in Western Africa : Commerce, Social Status, Gender, and Religious Observance from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2003).

- ↑ Ray, Carina E. (1 February 2014). "Decrying White Peril: Interracial Sex and the Rise of Anticolonial Nationalism in the Gold Coast". The American Historical Review. 119 (1): 78–110. doi: 10.1093/ahr/119.1.78 .

- ↑ Hardwick, Julie; Pearsall, Sarah M. S.; Wulf, Karin (2013). "Introduction: Centering Families in Atlantic Histories". The William and Mary Quarterly. 70 (2): 205–224. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.70.2.0205. JSTOR 10.5309/willmaryquar.70.2.0205.

- ↑ Ray, Carina E. Crossing the Color Line: Race, Sex, and the Contested Politics of Colonialism in Ghana. Ohio University Press.[ page needed ][ date missing ][ ISBN missing ]

- ↑ Ipsen, Pernille (2015). Daughters of the Trade: Atlantic Slavers and Interracial Marriage on the Gold Coast. ISBN 978-0-8122-4673-5. pp. 7.

- ↑ Ipsen, Pernille (2015). Daughters of the Trade: Atlantic Slavers and Interracial Marriage on the Gold Coast. ISBN 978-0-8122-4673-5. pp. 10-13.

- ↑ Ipsen, Pernille (2015). Daughters of the Trade: Atlantic Slavers and Interracial Marriage on the Gold Coast. ISBN 978-0-8122-4673-5. pp. 17.